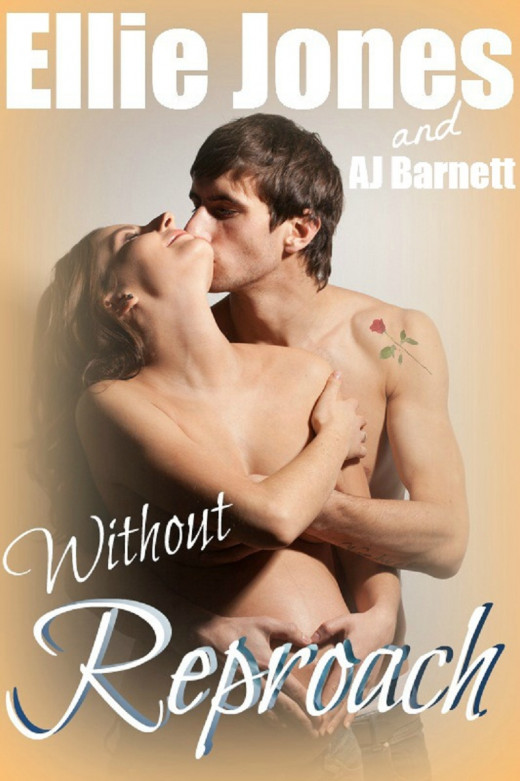

WITHOUT REPROACH - Adult Romance

Without Reproach

What people are saying about WITHOUT REPROACH

- "An impressive debut from a natural storyteller - contains all the elements essential for a good book" - Jill Lanchbery, author of "A Bucket of Ashes"

- "I loved your novel/story line. It kind of gave me the chills." - Carolyn Howard-Johnson, award-winning American author of "This Is the Place," "Harkening" and "Tracings"

- "Without Reproach" is, sexy, racy, and fast moving." - Ken Scott, international best selling author of "Jack Of Hearts" and "A Million Would Be Nice". He also includes it in his top-ten best-selling list.

Without Reproach is set in Spain

Synopsis

Jenny inherits a share in La Finca Piedra from Spanish artist, Juan García... yet has never met him, never heard of him and is not related to him. Jenny's psychological problems start when she sees the finca for the first time, yet vaguely recognizes certain parts. Worse, she discovers a nude painting of her in the entrance hall.

Eduardo, twenty years younger than half-brother Juan, is main beneficiary of the Will. Conflict erupts out of Eduardo's resolve to preserve the finca for the García family, and Jenny's determination not to give it up. She sees the finca as a chance of making something of her life. He sees her as a gold-digger. "You're so pompous," yells Jenny "You think you're the only person that counts; but you're not. Everyone matters, not just you."

The contradiction of aggression and tranquillity, of angry and obsessive feelings amid the calm surrounds of the beautiful Sierras, heightens the mood of WITHOUT REPROACH.

Jenny finds herself struggling with Eduardo on several levels; her escalating attraction, his promiscuous reputation, his belief that she may be involved with threatening letters against him, and his absolute and unjustified dislike of her new friend, Miguel... but then she starts to get threatening letters too.

Excerpt

The face in the mirror reminded her of a bad shave in a cartoon, full of nicks and scratches, and visible ends of stitches where flesh had been sewn back together. Cartoons were supposed to be funny, but this cartoon made her feel like crying, not laughing – where had her face gone.

Apparently, after they’d brought her in she’d remained unconscious for several days - and they said she was lucky … She felt like shit.

Her shoulder had been pinned together, her head, a tiny metal plate inside. It was true that only a small chunk of her swirling dark hair was missing but still it made her self-conscious. Her once petite nose was swollen, discolouration fading but noticeable, high cheekbones marred with stitches. She said, “You haven’t caught me on a good day. I could be bitchy.”

“You’ve been a hard person to trace, Jenny. I’ll manage.” The woman proffered her hand. “Maria Santos, abogada.”

Jenny frowned.

“You’d probably call me a solicitor back in Britain - a lawyer.”

“I know what an abogada is. I don’t understand why you’ve been tracing me.”

Jenny took the hand in her good hand as best she could. It still hurt her shoulder though, and wished she hadn’t. She’d almost learned to move without moving - would probably make a good busker when she got out.

Maria said, “Sorry! I should have realised. Are you feeling up to this?”

“I guess so, although I’m still a bit woozy. I’m afraid you’ll have to bear with me.”

“Say if you want me to leave.”

“I’m fine. I’ll be okay, just don’t expect too much.”

The abogada undid her attaché case, took out a sheaf of papers and studied them. “I’m afraid red tape in Spain is rather cumbersome. I sometimes wonder if one day we’ll get buried under our own paper work.”

Jenny became curious and struggled into a sitting position. Denia hospital was far from home and the prospect of company, a treat. The next bed was empty. It had been occupied for a while but the woman was gone, discharged. There’d been hardly anyone to talk to for days. Not that the woman had spoken much, but she’d been a face to look at, someone to share her frustration with.

“Is it the accident? I wasn’t driving you know. I can’t remember much about it but I know I wasn’t driving. I’d scrounged a lift after a party.”

There had been a confusion of red tail-lights, a blocked carriageway, the car jolting, scraping, bucking; nowhere to go before they hit metal. She’d drawn her knees up; instinctively lowered her head; willed her whole being to shrink up her backside. It was sounds she remembered the most; metal screeching, glass splintering, sounds she didn’t want to recall.

“It’s nothing to do with the accident.” Maria shook her head, her eyes on Jenny – perceptive - no sign of emotion. “Okay, so let’s start with your full name.”

“Jennifer Alicia Bucknall… What’s this about?”

“Do you have Spanish nationality?”

“No. Born and bred in England.”

“The maiden name of your mother?”

Jenny had to think hard, paddled through a head full of thick soup, but it came eventually. “Olive Grace Peterson.”

“Tell me about your father.”

“I can’t remember my father.” Jenny screwed her face. “I don’t think I ever saw him. His mother was Spanish, though. I think he died over here.”

Maria wrote it down, seemed satisfied.

“I’m sorry. I can’t seem to remember much. It annoys me, but they say it’s not unusual.” Jenny pointed to where the plate was on her head. “They’ve put a trap door here so that if things get bad you can open it up and dig out the memories for yourself. I keep forgetting things, silly things, not everything… God knows why. They say it’ll get better with time … Look, what’s all this about?”

There was a vase of flowers on the bedside cabinet, flaccid in the heat. Maria pushed herself to her feet.

“Your flowers, shall I give them fresh water? It’s a shame to let them spoil.” She sniffed at them, took them to the sink in the corner of the room, filled the vase, and brought them back. “You have proof of your identity?”

“I guess so - passport, bankcards. They’ll do, won’t they?”

“I wonder if I could see them.”

Jenny heard the murmur of a television in the common room, a scrape as someone moved furniture, hushed conversations. The wearisome familiarity of the place depressed her. It felt as if she’d been lying in that room forever. Maria Santos made a welcome break and she intended hanging onto her for as long as possible. If it involved answering questions then so be it. She said, “There’s no harm in you seeing my passport. You’re not touching my bankcards, though.”

“Very wise.”

“There’s a clutch bag in the cupboard by your side. My passport should be in the zip pocket…Look, do you mind telling me what’s going on?”

“Please bear with me, Señorita.” Maria found the bag, took out the passport, studied it, checked the date of birth, looked at Jenny and compared her to the photograph, put the passport away again, wrote on the paper, then offered it to Jenny. “Would you mind signing this?”

“Difficult. My shoulder, I can’t use my arm. I’m right-handed.”

Maria smiled wanly, “Sorry! No worries. It can be done later. I’m satisfied you’re the person I’m looking for.”

“The significance being?”

“Juan García. Juan Cabra-García to be pedantic. Cabra was his mother’s family.”

Jenny shook her head from side to side. “No! You’ve got me there. His name means nothing to me.”

“He died a few months ago, in that terrible bomb in Madrid. In his last Will and Testament, he made you heir to La Finca Piedra, along with his younger half-brother.”

Jenny stared.

“It isn’t an even split. His brother has the major share, but these are details we can go into at a later date.”

“I really don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“The important thing is, we’ve established your identity.”

“But I don’t know a Juan Cabra-Garcia.” Jenny closed her eyes, thought hard. There was nothing.

“There will be formalities to go through, and documents need to be drawn up. A Public Notary will need to verify the documents to legalize them. But these things are only a matter of time.”

Jenny said carefully, “I rather think you’ve made a mistake.”