An Afternoon with Georgia O’Keeffe

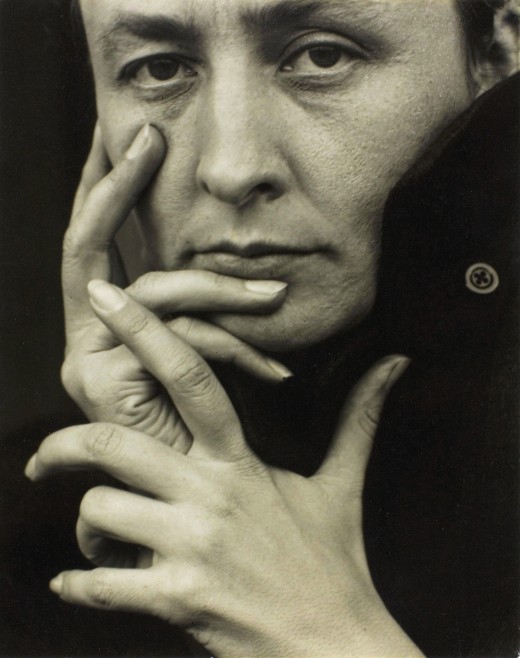

I have been looking through several books of Georgia’s artwork for the past few hours. The library is occupied by many people but the silence is deafening. With each turn of the page I fear I am disturbing the closest person to me, about 10 feet away. Georgia’s paintings brighten the dull atmosphere. The rich colors and vibrant themes jump off the page and straight into my imagination. The lilies dance and the clouds move. Their detail, although in one and two dimensions, is infinitely expanding. There is so much life in each and every work Georgia O’Keeffe created. Georgia O’Keeffe. Georgia O’Keeffe. Is there any other name that whispers femininity in the Southwest? Georgia O’Keeffe made up her mind at the age of twelve that she would become an artist[i] and she has since left a lasting legacy of beautiful nature in her paintings. Georgia’s floral and representational paintings are related to both traditional and nontraditional subjects.

Hub on the Definition of Southwest

- What is the Southwest U.S.?

See the beauty of the Southwest and find out why the location of the Southwest is debatable.

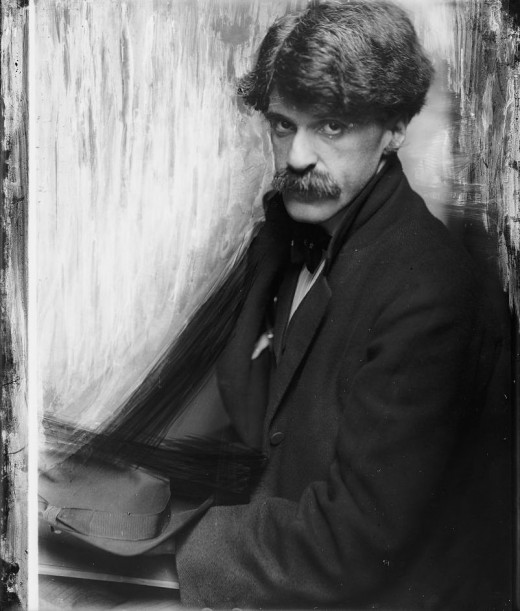

Georgia’s life has been meticulously documented in the many books solely dedicated to her. Mr. Drohojowska-Philp proudly tells us “She was born on a dairy farm three and a half miles southeast of Sun Prairie on November 15, 1887”[i]. Upon further reading, Sun Prairie is stated as being in Wisconsin. How does a Wisconsin girl in the late 18th century end up in Taos, New Mexico? A librarian asks if I am finding everything I need. “Yes, thank you.” Back to work. Apparently, as Ms. Britta Benke plainly points out, Georgia’s family moved to Williamsburg, Virginia when she was fifteen[ii]. Later, in 1907, she left to study in New York at “the Art Students League, the most famous art school of the day”[iii]. By the time she was 30, Georgia was living with Alfred Stieglitz, a much older man, in New York[iv]. Their love was quite intense and both were happy. Can love like this still exist? A girl holding many books almost trips on the carpet in front of the spot I have chosen to sit on while I read and think. The windows in the fine arts library are extremely large and the Sandia Mountains are very easily seen in the warm spring afternoon.

New Mexico Hubs

- An Architectural and Spiritual Awakening in the Heart of Albuquerque

Verbally explore a place where spiritual enlightenment is enhanced by the architecture and décor. - Hot Air Balloon Rainbows Over Albuquerque

- Indigenous Paleosols on the Jicarilla Apache Reservation

A scientific study on soils in northern New Mexico. - The Burning of Zozobra

Read about a Santa Fe tradition in which a man is ritualistically burned at the beginning of each fall season.

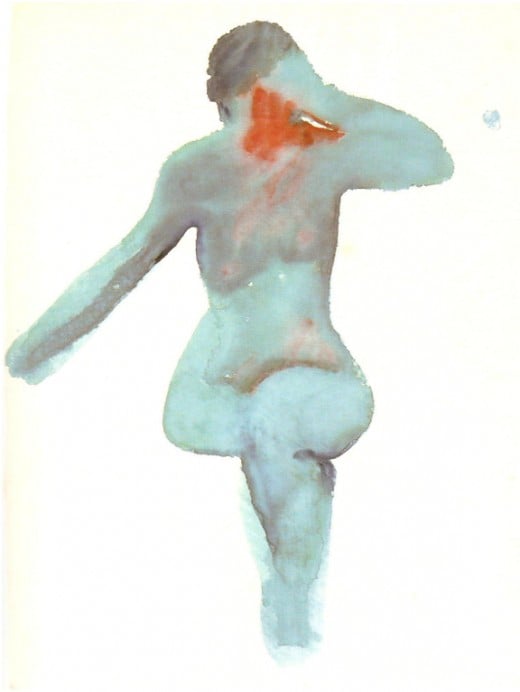

As I turn the page, a painting jumps off the page. Wow! In 1917, just before she moved in with Stieglitz, Georgia finished the Nude Series VIII. It is the small 45.7 by 34.3 centimeter watercolor I am currently looking at and is seen in Figure 1 for you to enjoy as well. The small size and use of watercolor illustrates how, at the time, Georgia was a budding artist in the big city. She did not yet have the money to create larger works. The contrasting colors make it really stand out against the beige paper in the background. There are no objects in the background and no frame, just the figure. It is a silhouette of a woman sitting in a natural position that gives the illusion of space. The figure is fairly abstract and representational. Could she be an abstract representation of a staged model? I think not. Her right hand is reaching downward, as if touching the surface she is sitting on. Her left hand is gently rubbing her head. She could be a woman undressing at home on her bed, getting ready to take a shower. She looks comfortable. Although only the outline of this beautiful woman is clearly visible, it is quite evident she is naked. The blue watercolor darkens around her breasts, as if to give them more depth through shadows. And, her nipples are highlighted in red. In addition, the woman’s face and a small portion of her lower body are also highlighted in red. The highlights appear to emphasize her femininity. Her facial features are not clearly visible but the dark blue atop her head appears to represent hair. Also, her breasts are quite out of proportion to her body. Her breasts are different sizes and one nipple is higher than the other. Furthermore, the woman’s hips are quite wide. I believe the accentuation of her femininity also stresses the fact that women are not perfect. Women are full of flaws and should not have to conform to other people’s ideals of the perfect slender woman with large breasts and a beautiful face. I wonder. Were these issues important during the time Georgia created this beautiful woman? I am not at all sure but I can see how this nontraditional image, in the sense that at the time of its inception women did not often draw the female nude, is important in the evolution of women in art.

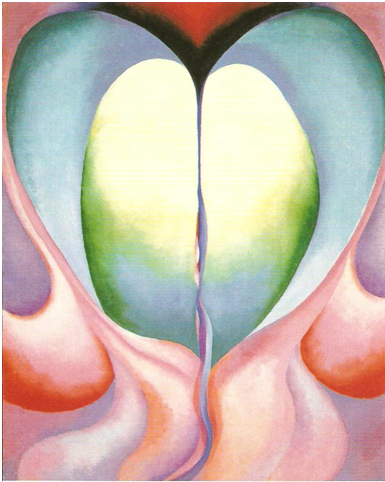

As I flip through a few pages another equally impressive painting offers itself for a visual analysis. In 1919, a few years after moving in with Stieglitz, Georgia painted the 50.8 by 40.6 centimeter Series I, No. 8, as seen in Figure 2, with oil on canvas. The vibrant, lively, organic colors emphasize the obvious heart shape. This painting most likely expresses the love and happiness she felt at the time, having moved in with Stieglitz only a couple of years prior to its inception. I can feel the love and happiness emanating from this painting. The emotions are so intense. I am happy. I am loved. The pinks and purples work to outline the shape while the inside is green in some areas, blue in others, yellow in some instances, and a dark blue with small hints of pink and red form a line of symmetry down the center of the heart creating. One cannot help but notice the strangeness of the pink, red, and blue line. My imagination begins to build an oddly familiar image. The folds, crevices, and small slices of pink appear to look like those of a female vaginal area. In addition to representing love, this painting appears to also represent femininity. In the first respect, the painting is traditional; women are often associated with love. In the latter respect, the painting is nontraditional because paintings of such parts of the female body are often considered taboo in fine art.

Alfred Stieglitz and many other critics believe Georgia’s paintings were feminist representations of the world; therefore, “she hoped to refute the sexualist interpretations which, from the start, had been placed upon her abstract work”[i]. Apparently, although feminine constructs appear to permeate Georgia’s work, she herself did not view them in that manner. How interesting. It must be quite frustrating to personally view your art one way and have other people misinterpret it in another.

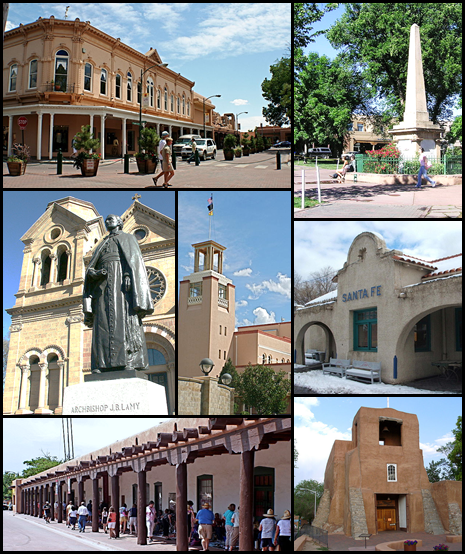

Flowers and skyscrapers is the next chapter in Benke’s O’Keeffe. I am quick to wonder what one has to do with the other. I have come to read that during the period between 1918 and 1932 Georgia “produced more than 200 flower paints”[i]. Flowers are quite organic. They are natural. They represent the beauty found in nature. In addition, Georgia is most known for her floral paintings. Skyscrapers are extremely inorganic. The linearity often associated with them is not usually found in nature. Unnatural straight lines come together to compose massive concrete and metal structures. Furthermore, I am informed that Georgia married Alfred Stieglitz in 1924 and during this period they lived in New York, for the most part. The title Flowers and skyscrapers now makes sense. I believe it is natural for a farm girl like Georgia to be enchanted with both subjects. Also being from a small town, I know how important and dominant nature is in everyday life. Georgia painted what she knew and her childhood familiarized her with nature. Then as an adult, the city life, dominated by skyscrapers, became her world, for a time. Once again Georgia painted what she knew and at the time that was the gigantic skyscrapers of the New York skyline. Following several trips to New Mexico, in 1931, Georgia began spending summers in Taos, New Mexico[ii]. This is where my home state begins to influence her work. Georgia is quoted as saying,

“The moment I saw the brilliant, proud morning shine high up over the deserts of Santa Fe, something stood still in my soul, and I started to attend. There was a certain magnificence in the high-up day, a certain eagle-like royalty…In the magnificent fierce morning of New Mexico one sprang awake, a new part of the soul woke up suddenly, and the old world gave way to a new”[iii].

Her love of the New Mexico landscape, climate, culture, and essence had begun. In 1940, Georgia bought a house near Ghost Ranch, New Mexico. Upon Stieglitz’s death in 1946, she spent a few years in New York then began living primarily in New Mexico. Her life in New Mexico is very clearly seen in her later work.

With the turning of a page, the breath taking Summer Days work is introduced. The painting is seen in Figure 3. It is 92.1 by 76.7 centimeters and was painted using oil on canvas. The painting is dominated by detail and the skull of a deer head. The antlers rise mightily toward the top of the canvas. The shadows of the skull help accentuate the features. I believe Georgia may have been drawn to painting bones because of their beauty. When bones are clean they are white, almost pure. They represent the death of an animal. They represent the harshness of living in New Mexico. The dry, arid climate limits the number of animals that may populate the area because water is often hard to come by. I also believe the skull draws Georgia away from the traditional view that she primarily painted feminist representations, such as flowers. A skull is anything but feminine. The skull allowed her to grow to become an independent woman artist, who did not have to rely on her interpretations of feminist ideals to maintain her standing as a good artist. Immediately below the skull are wild flowers. Unfortunately, I am not an ecologist and have no idea what kind of flowers they are but I believe the larger one, the sunflower is a Native species of New Mexico. They are the only sign of femininity in the painting. The flowers lead the eye to the bottom of the painting where it is discovered that the top portion of the painting is actually taking place in the clouds. In the distance a storm appears to be on its way. The sky gives the painting the illusion of depth. Further accents of depth are the mountains in the foreground. The colors are in different hues that make them appear as if light is casting shadows upon them. They look very realistic, like the mountains and hills found all over New Mexico. The painting appears as a dream takes the dreamer into the far reaches of the desert, where animals can no longer exist and the presence of small wild flowers are wished for. Oh, how I wish I could be amongst the natural environment outside, instead of being cooped up in the library all afternoon. The number of occupants is beginning to dwindle. The sun is setting. 6:30 already, it is late.

Benke sadly announces, “Georgia O’Keeffe died on 6 March 1986 at the age of 98 in Santa Fe”[i]. She lived her childhood dream of being an artist. Despite her objections, Georgia’s work is still quite often viewed as being feminist. It complex, detailed, abstract, representational, controversial, traditional, beautiful, and displays the truth in both natural and urban forms. Georgia’s traditional and nontraditional subjects of floral and representations make her a very appealing and talented artist. Now all books are closed and the sun has set on another gorgeous Albuquerque day. I am free to wonder about the nature Georgia so implicitly illustrated in her art.

Works Cited

[1]Benke, Britta. O’Keeffe. p. 7. 2000. Taschen, Koln.

[1] Drohojowska-Philp, Hunter. Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O’Keefe. p. 13. 2004. W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

[1] Benke, Britta. O’Keeffe. p. 7. 2000. Taschen, Koln.

[1] Benke, Britta. O’Keeffe. p. 7. 2000. Taschen, Koln.

[1] Garden Castro, Jan. The Art & Life of Georgia O’Keeffe. p. 42. 1985. Crown Publishers, New York.

[1] Benke, Britta. O’Keeffe. p. 38. 2000. Taschen, Koln.

[1] Benke, Britta. O’Keeffe. p. 31. 2000. Taschen, Koln.

[1] Benke, Britta. O’Keeffe. p. 56. 2000. Taschen, Koln.

[1] Benke, Britta. O’Keeffe. p. 55. 2000. Taschen, Koln.

[1] Benke, Britta. O’Keeffe. p. 86. 2000. Taschen, Koln.

© 2014 morningstar18