Indigenous Paleosols on the Jicarilla Apache Reservation

My soils project began with the notion that I wanted to study soils on my reservation, the Jicarilla Apache reservation located in northern New Mexico. Although I have lived in the city almost all of my life, that profound sense of identifying myself as an American Indian and the subsequent close connection to the land from which my ancestors came from and which I will be buried in made it necessary for me to study soils on my reservation. The purpose of my soils project is to apply the soil classification system learned in class to the soil properties of my reservation and make an interpretation of the environment the soil formed and continues to form in today.

Hub on the Definition of the Southwest

- What is the Southwest U.S.?

See the beauty of the Southwest and find out why the location of the Southwest is debatable.

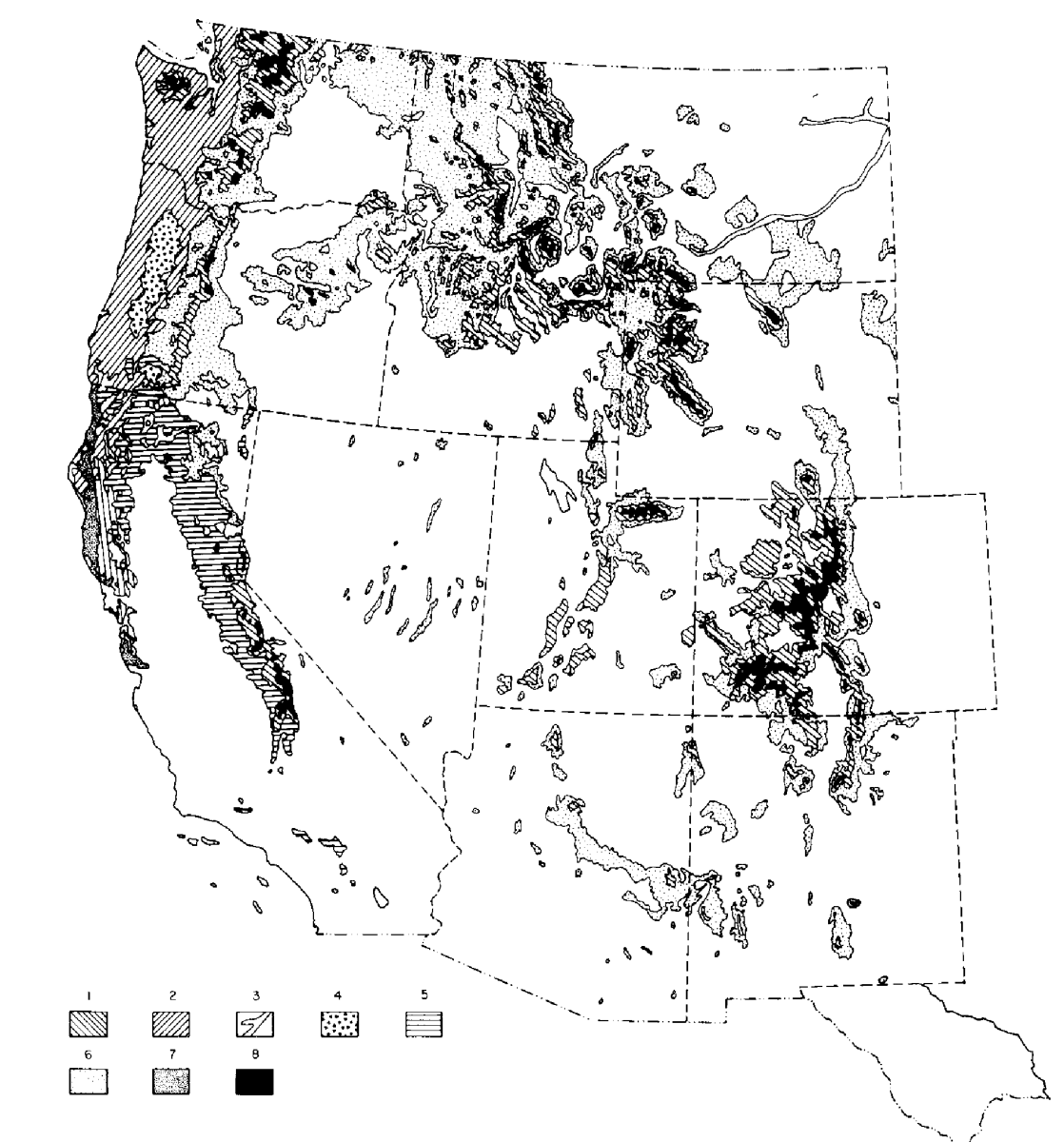

I set out to do an initial analysis of the terrain on the southern half of my reservation and, luckily, a couple of friends of mine from the Jicarilla Apache Nation Oil and Gas Administration, whom I had not seen in quite some time, eagerly joined my excursion into the oil and gas fields. The sky was clear, the temperature was a mild 65oF, and, as usual for the time of year, there was absolutely no traffic on the dusty dirt roads that led from one well to the next. Everything was going great until I reached my study area, seen in Figure 1. I had anticipated studying soils in relation to hill slope and vegetation; however, the phenomenon I was looking for was nowhere in sight. The mesa did indeed have sparse vegetation here and there, mostly sagebrush, cedar, pinion, rabbit brush, and yucca, but there was no relation to their growth and the hill slopes of the mesa cliff faces. Instead, the terrain was dominated by what appeared to be buried soils that had beautiful multicolored horizons, seen in Figure 2. Unsure of how to proceed with my project, my companions and I called it a day and I began the two and half hour drive back to Albuquerque while listening to the great 70s and 80s bands like Fleetwood Mac, The Beatles, and REO Speedwagon.

Hubs on "The Control of Nature"

- Cooling the Lava: The Battle to Save Heimaey

Read about the terrifying ordeal of waking up to an active volcano erupting just outside your front door and how a town was sacrificed. - Controlling Nature?

A look at John McPhee's several examples of failed attempts to control nature in "The Control of Nature." They are given to illustrate that people are the mercy of the elements.

After a brief visit with my advising professor about the relevance of studying buried soils, in this case, also known as paleosols, I was given several scientific papers written by Greg Retallack to read. While reading these highly informative papers, I learned that Paleosols are loosely defined as, “a former soil buried by later deposits” (Retallack, 1981). In addition, Retallack states two obvious ways to identify a paleosol. The first is the idea that, “The delineation of nodules, concretions, and horizons is often much sharper in older fossil soils than in modern soils” (Retallack, 1981). As seen in Figure 2, the horizons are much more distinguishable than modern day soils. The second way to identify a paleosol is dependant the position of my reservation. My reservation is located in the San Juan Basin. Retallack says, “The ideal situation for the preservation of fossil soils is in sedimentary basins subsiding at such a rate that soils are covered and sink below the water table shortly after reaching the greatest differentiation possible, given the parent material, vegetation, and climate at the time” (Retallack, 1981). The fact that both of these identifiers are true in regards to my reservation confirmed my notion that the soils on the southern half of my reservation are indeed paleosols.

After this revelation was cleared up, I had to set aside another day to return to the site to do an in-depth soil analysis; therefore, I returned to my homeland the following week on a day strikingly similar to the first day. I was lucky enough to return before the annual winter snow began to fall and I was quite grateful for this. My team from Oil and Gas once again accompanied me and they were very interested in learning about how to classify soil properties. Their curiosity about soils made me test my knowledge of how classifying is done and I was happy to be the instructor for once. However, I knew classifying and identifying paleosols is no easy business. Ratallack said, “Just as modern soils are known to be products of many interacting factors, the interpretation of Precambrian paleosols must take into account complications such as metamorphism, clay diagenesis, original permeability, organic matter content, paleodrainage, and parent material” (Retallack, 1986). Although this is true I began the task at hand by analyzing a mound of paleosol horizons, as seen in Figure 3.

Hub on How to Write a Scientific Paper

- How to Write a Scientific Paper

Outlines good practices while writing college essays for sciences courses or scientific papers for publication.

I found 10 distinct soil horizons that I distinguished purely based on color. Each horizon is a different color, as you can see in Figure 4. The properties I found are listed in Table 1. All the horizons I found have the subordinate b distinction because all the horizons I studied were buried soils. I decided to classify the first three horizons as C horizons because they lacked properties of O, A, E, or B horizons. They were gravelly sand horizons with an olive color. The following six horizons were reddish/brown B horizons with high clay content that resulted from pedogenic processes. These horizons are similar to the ones Retallack described by saying, “For red beds, including fossil soils, it is likely that the original oxidation and formation of yellow or brown ferric oxyhydrate minerals occurred during soil formation, but that the reddening of the deposits occurred during late diagenetic alteration of these minerals to the brick-red mineral hematite” (Retallack, 1983). This implies that the color of these horizons occur after deposition and is a result of diagenic processes. I classified the final horizon, and the most interesting, as an A horizon because its charcoal color indicated the presence of large quantities of organic material. In addition to its striking color, the A horizon contained microscopic pore spaces that more than likely housed prehistoric roots. Although the A horizon had been significantly altered by pedogenic processes the dark color and presence of root pores indicates an environment that was once rich in plant life. After this last horizon had been classified, it was time for my group to say goodbye again but with the knowledge that I would not be returning the following week for another follow up analysis. After the well wishes were expressed, I made my way back to Albuquerque, this time listening to the likes of classic country singers like Patsy Cline, Hank Williams Sr., and George Jones.

Table1: Soil Properties

Horizon

| Depth (cm)

| Color

| Structure

| Texture

| Effervescence

| Boundary

| Clay Films

| Roots

| Pores

| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cbk1

| 0-50

| 2.5Y 7/1

| Blocky

| Gravelly Sand

| Mild

| Abrupt

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Cb

| 50-120

| 5Y 5/1

| Fine Subangular Blocky/ Granular

| Gravelly Sand

| None

| Diffuse

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Cbk2

| 120-126

| 5Y 7/1

| Blocky

| Gravelly Sand

| Mild

| Diffuse

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Bb1

| 126-236

| 5YR 4/3

| Fine Subangular Blocky/ Granular

| Sandy Clay

| None

| Clear

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Bbk1

| 236-259

| 10YR 6/2

| Fine Subangular Blocky/ Granular

| Sandy Clay Loam

| Very Mild

| Clear

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Bbk2

| 259-276

| 7.5YR 7/1

| Platy

| Sandy Clay

| Very Mild

| Clear

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Bbk3

| 276-296

| 10YR 8/1

| Fine Subangular Blocky/ Granular

| Clay Loam

| Slightly

| Clear

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Bb2

| 296-301

| 5Y 7/1

| Fine Subangular Blocky/ Granular

| Sandy Clay Loam

| None

| Clear

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Bbk4

| 301-319

| 10YR 7/2

| Fine Subangular Blocky/ Granular

| Silt Loam

| Slightly

| Clear

| None

| None

| Interstitial

| |

Ab

| 319-391

| 5Y 4/1

| Fine Subangular Blocky/ Granular

| Silty Clay

| None

| Abrupt

| None

| Few

| Interstitial

| |

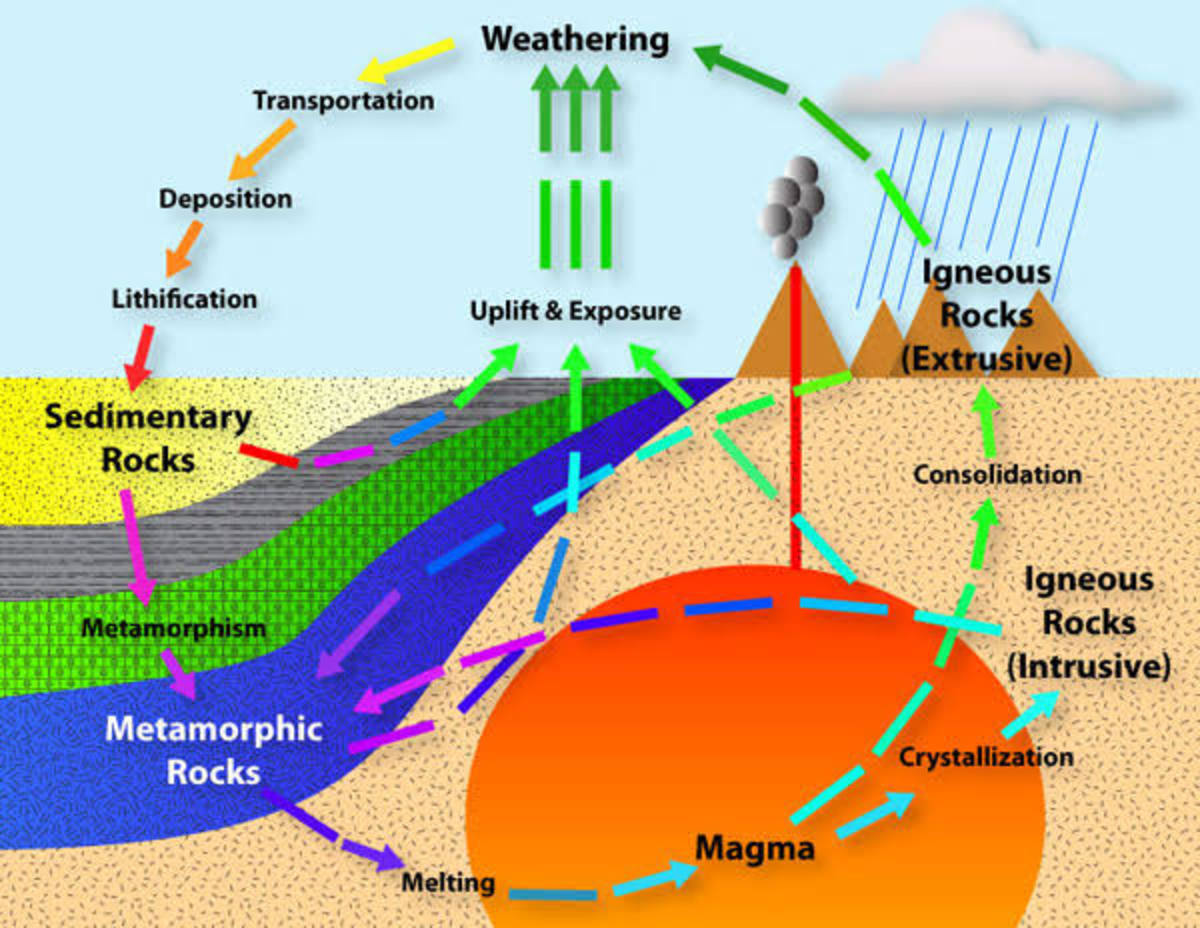

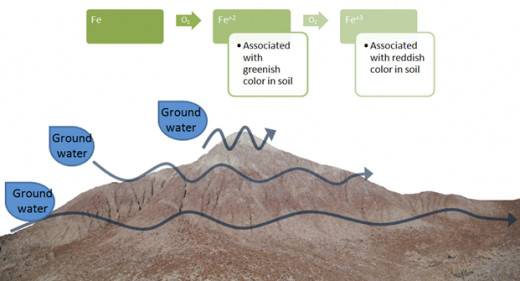

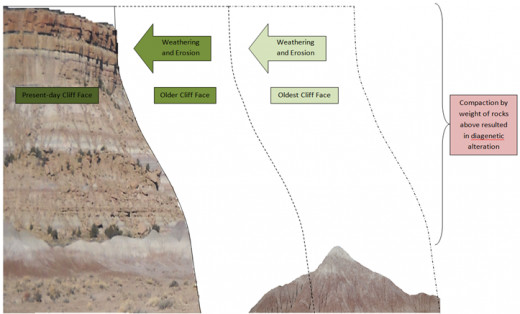

As the days began to near the date of presentations, I found myself a little bewildered as to how to approach the interpretations part of my study; therefore, I scheduled an appointment with my advising professor. He cleared up a couple of concepts I was having trouble interpreting. The first is the color variation in the soil horizons. They are beautiful fluctuations of gray/olive, red, and purple/maroon. My advising professor reminded me of a concept I had read about in Retallack’s 1986 paper. He states, “Under conditions of low amounts of available oxygen within the soil there may not be enough to oxidize the large amounts of iron released from iron—rich rocks by the action of carbonic acid derived from CO2. This much iron remains reduced and is washed out of the profile” (Retallack, 1986). This idea is displayed in Figure 5. As oxidation of iron occurs with ground water, the iron is reduced to Fe+2 and Fe+3. Fe+2 the iron that is usually found in the greenish/olive color in soils and Fe+3 is usually associated with the reddish color in soils. In addition, my advising professor explained that the reason the mound I studied is still intact may be due to the soil properties of the first three horizons. Remember how gravelly and cemented they were? The reason those first three layers are so compacted is because at one time they were most likely an underlying soil horizon in the cliff face. As time passed, weathering and erosion ate away the cliff face and made it retreat, as seen in Figure 6. Since the first three horizons were so compacted and hardened over time, they keep the mound intact because they are hard to weather; however, with more time, weathering, and erosion, the mound I studied will eventually be worn down to the point that it will no longer be a mound. With this newfound information, I was successfully able to complete the interpretations portion of my soils presentation.

Hubs on Scientific Topics

- Do You Know What Else Crude Oil Makes?

If the first thing you think of when you think crude oil is gasoline for your car, you might want to consider that crude oil is a crucial component in making these far more essential products. Simply reading the paragraph titles will give you a bette - You Are Currently Moving at about 1,000 mph!

- Do You Know What Peak Oil Is? If Not, You Should

For many decades, there has appeared to be an unlimited supply of oil but, like all good things, its time will come to an end. - Predicting Future Sea-Level Change

Predicting future sea-level change by looking at ways present sea-level is monitored. Understanding and predicting future sea-level change is important because Earth’s climate is also changing. - How to Write a Scientific Paper

Outlines good practices while writing college essays for sciences courses or scientific papers for publication.

After driving an overall total of over 10 hours (counting the hours I spent driving around with my Oil and Gas friends), my soils project was completed and my goals for this project were successfully achieved. I was applied the soil classification system to some of the soil properties of my reservation and I made an interpretation of how the soil formed and observed the soil as it continues to form in today. I also gained a much better understanding of the land my reservation sits on. As a Jicarilla Apache, I was taught that the land is important because it is what gives life. I think studying the soils on my reservation gave me an enhanced appreciation for the land because I was able to study firsthand the harsh soil that my ancestors lived in and roamed about on. Their presence is still felt there in the ruins that permeate the area and heard in the whispers of the wind that blow through the canyons and mesas. I am proud to say that I too am tied to the land.

Works Cited

Retallack, Greg. “A Paleopedological Approach to the Interpretation of Terrestrial Sedimentary Rocks: The Mid-Tertiary Fossil Soils of Badlands National Park, South Dakota.” Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 94, p. 823-840. July 1983

Retallack, Greg. “Fossil Soils: Indicators of Ancient Terrestrial Environments.” Paleobotany, paleoecology, and evolution, v. 1, p. 55-102. Praeger Publishers, New York: 1981.

Retallack, Greg. “The Fossil Record of Soils.” Paleosols: Their Recognition and Interpretation. Ed. V. Paul Wright. p. 1-57. Princeton University Press, New Jersey: 1986.

© 2013 morningstar18