- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

American Civil War Life: Filling the Ranks – Introduction, and the Militia

[I never dreamed a brother of mine would ever] "raise a hand to tear down the glorious Stars and Stripes, a flag that we have been taught from our cradle to look on with pride. . . . I would strike down my own brother if he dare to raise a hand to destroy that flag. We have to rise in our might as a free independent nation and demand that law must and shall be respected or we shall find ourselves wiped from the face of the earth . . . and the principles of free government will be dashed to the ground forever."

- James Welsh, Illinois (originally Virginia), to brother John Welsh, Virginia, 1861

ACWL: FTR - Introduction, and The Militia

Introduction

With men rapidly “springing to the call” for service in the U.S. Army, whether as Militia, Volunteers, or Regulars, there soon arose the need to form these men into an effective armed force. Thus, the next step was to organize and supply them.

Starting at the smallest level, units were consolidated into military formations of progressively larger, and more unwieldy, size. To keep these large formations and thousands of men amply supplied and healthy was another variable in the complicated equation of army operations. Good officers were needed to handle all of these command-and-control responsibilities.

I shall detail for you, in this series:

The Militia

The Organization Of, And Choosing, The Company

The Volunteers and The Regulars

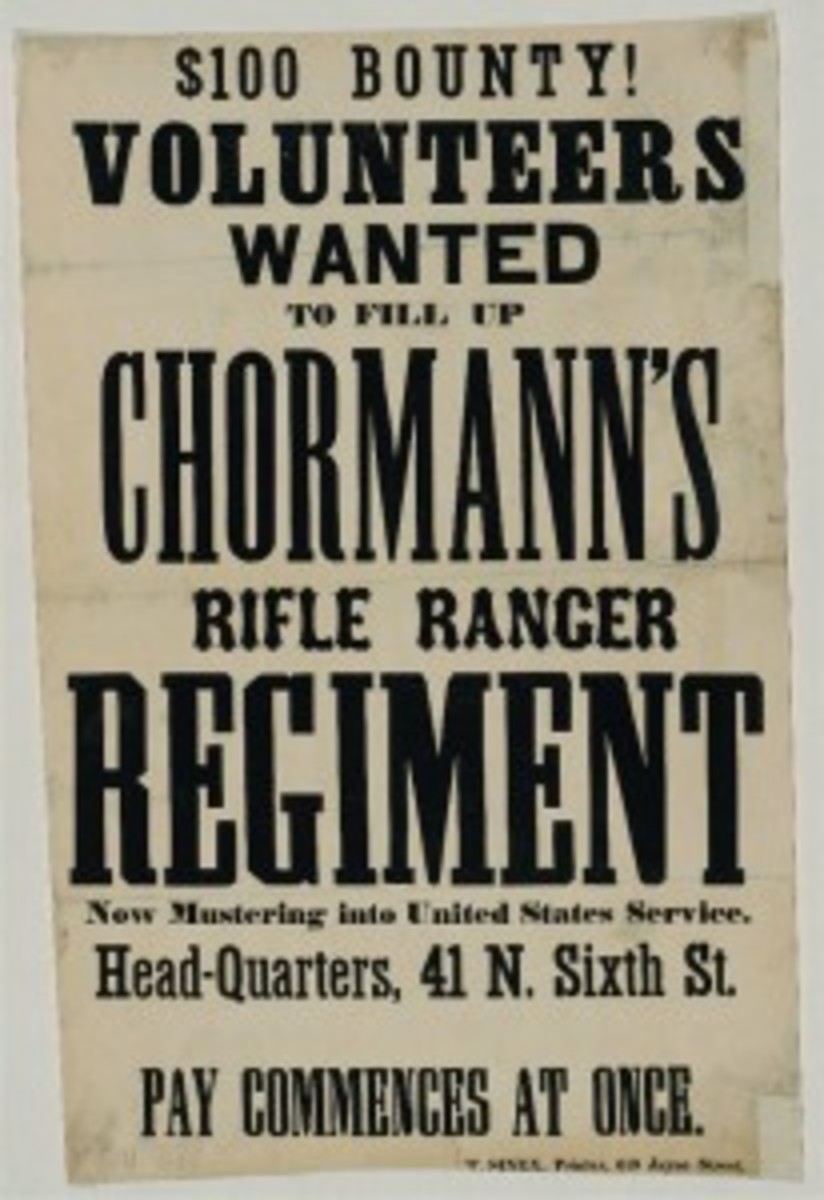

Rallies and Recruitment

Order of Battle: Regiment/Battalion

Order of Battle: Brigade and Above

“If it is worth a bloody struggle to establish this nation, it is worth one to preserve it.“

Oliver P. Morton, Governor of Indiana, November 22, 1860

The Militia

From my previous American Civil War Life series, The Union’s Path To War, you will recall that, in response to the attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln immediately issued a call to the loyal states for 75,000 Militia to serve the federal government for 90 days.

What was the Militia (aka “Three Months Men”)?

“Militia” is defined, in rough terms, as a force of civilians, raised from the general population, to serve military duty. This was done in order to augment the strength of the National Army during a national emergency. Rather than merge with existing units in the U.S. Army, however, Militia members served together in their own Militia units.

How was the Militia different from the federal military?

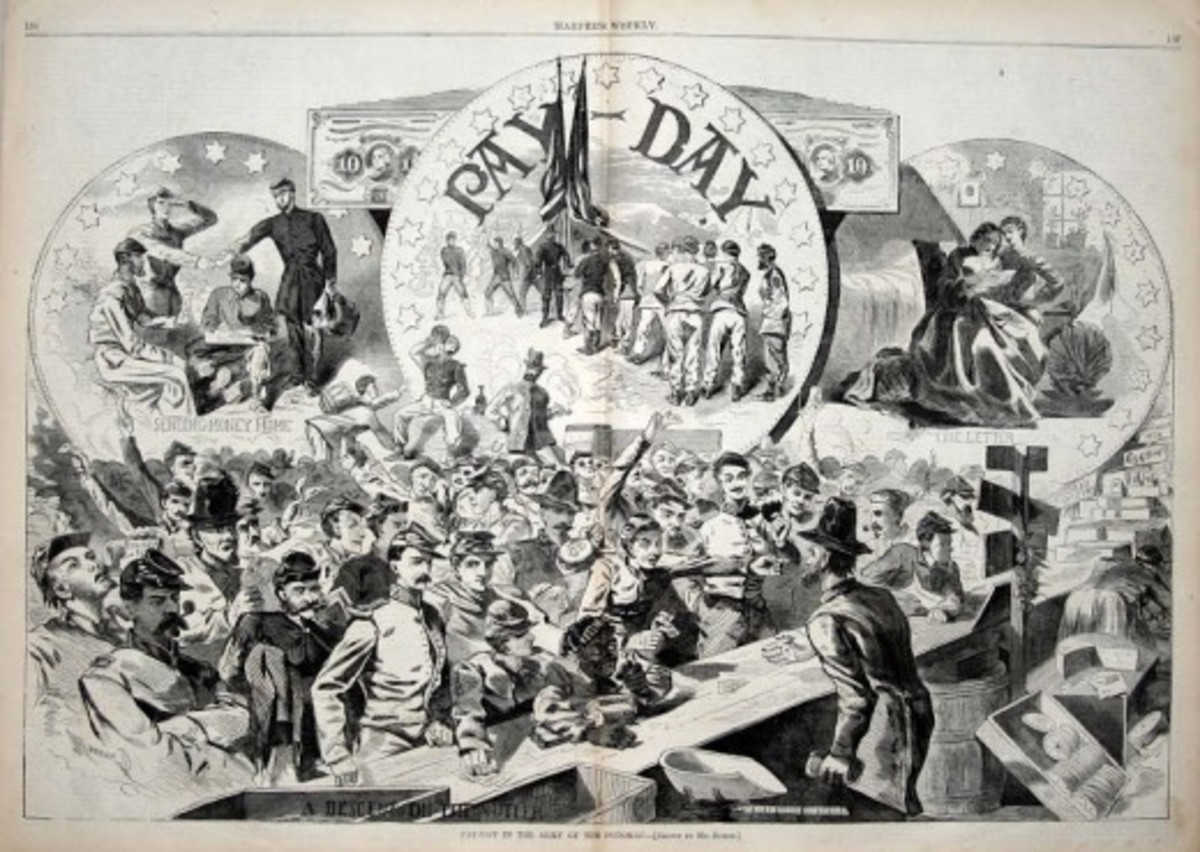

Militia members were not paid soldiers. Troops in federal service, on the other hand, were paid a regular wage. Militiamen were also not officially part of the U.S. Army, though they often were under U.S. Army command. Militiamen served as ad hoc auxiliaries to help the U.S. Army, or otherwise to provide a semblance of military protection and utility in terms of crisis. The Militia units were normally “under arms” for only as long as the crisis dictated. In the cases of civil disturbance, the Militia may have been under arms for only a few days or a few weeks. In the case of war, the Militia may have been under arms for much longer periods of time, perhaps years.

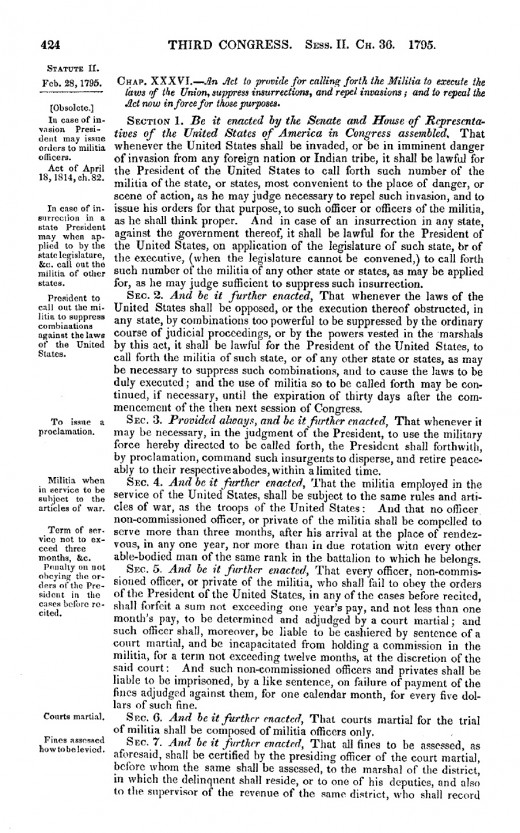

Unless specifically called for federal service by the standing president (which was allowable under the Militia Act of 1795), the Militia served only within their respective states. When the Militia was called to federal service after Fort Sumter’s surrender, they thus began serving the United States as a whole. They were then eligible for the standard soldier wage for as long as they were in the service of the federal government.

The Militia units in the United States at the time of the American Civil War may have existed since the Revolution, if not before. At that time, state Militia service in the U.S. was compulsory. However, due to the changing times since then, compulsory Militia service was eventually abolished in many states. In some newer states, there was never compulsory service and, thus, few or no Militia units.

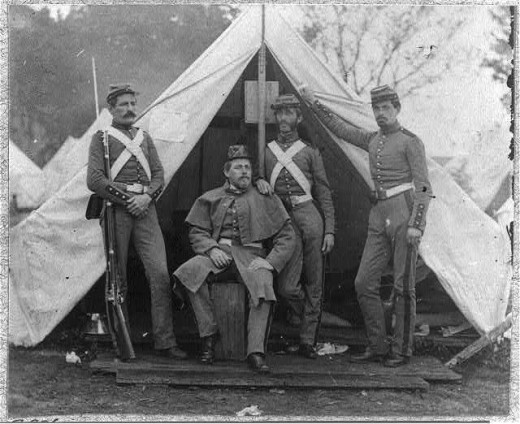

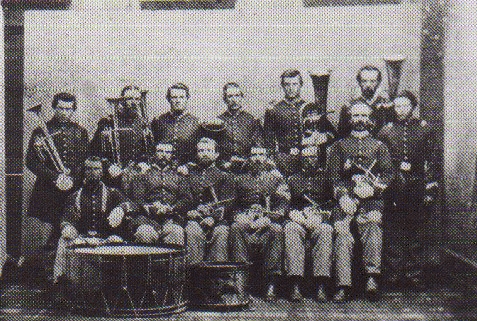

Several Militia units were formed by local civilian groups. These were men that liked to call themselves “soldiers”, but did not really go through the training or the experiences necessary to actually BE soldiers. Their units were more like gentlemen’s clubs than useful armed forces.

Militia officers were elected to their posts by the members of the Militia unit. This meant that popularity was often a more crucial factor than competence in deciding the unit’s leadership.

Many Militia members owned their uniforms, accoutrements, and weaponry. As there was often no standard, statewide set of regulations, each Militia unit could have required a completely different set of clothing and equipment than the others, even if they were from adjoining geographic areas.

Militia units not only came in multitudes of uniforms and weapons, but also in discipline and training. Marching in parades was often the only times they assembled, so the usefulness of these units in armed confrontation was often in question. There were the exceptions – some Militia forces were very well-trained and equipped – but by and large, training and discipline in Militia units was uneven or barely existent.

Militia units were often required to meet once or twice per year to drill. Sometimes these drill meetings were statewide, meaning all units in the state were expected to attend. There were fines for those members that did not show up to do so. However, many members decided to forego these drills and either chose to pay the fines or, in most cases, chose to ignore the fines altogether. As there were few attempts at enforcement of collecting the fines, the choice to ignore them seemed to be safe enough.

Why were Militia forces still accepted, and considered credible, by the country?

There was a thought in those days that citizen-soldiers, raised only for national emergencies, made better troops than those that soldiered for a living. After all, it was reasoned, citizen-soldiers, not professional soldiers, defeated the standing British Army during the Revolution (though that explanation is hardly accurate). In any case, it was thought better to have large amounts of Militia forces, for small periods of time, than a large, standing National Army for indefinite periods of time. A small, standing National Army required less taxation revenue as well!

After the fall of Fort Sumter, and the call for Militia, the existing United States Militia units began assembling (if they had not done so already). State governors were alerted by the federal government for the need for a certain number – otherwise known as “quota” - of state Militia. State governors, in turn, alerted the Militia commanders. The Militia commanders hastened to alert the members of their units to assemble at appointed locations and dates. Meanwhile, the state went about purchasing supplies and equipment, not already owned by the Militia, that were needed for extended out-of-state service in the field. These appropriations included ammunition, blankets, knapsacks, etc.

As the Militia assembled, the governors consolidated these units into larger combat forces, appointed or confirmed commanding officers, and sent them on their way to Washington City, or to any other points in which they were needed.

As they were not “U.S. Army”, each Militia member actually had the option to serve, or to be discharged, before being sworn into federal service. However, he needed to decide very quickly which option he preferred. If he was opposed to serving, he was discharged. Those who were discharged were usually scoffed-at by former comrades and fellow townspeople. The act of returning to civilian life, rather than face the life-threatening prospect of being in battle, was considered cowardly.

Afterword

The next article in this series is called American Civil War Life: Filling The Ranks - Organization Of, and Choosing, The Company.

© 2013 Gary Tameling