- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of Europe

Danelaw Years - 9: Jorvik, Home to Kings and Craftsmen, Warmakers and Traders

Eboracum, Eoferwic, Jorvik to York - a painless transition?

Eboracum, Eoferwic, Jorvik or York, the city has had a chequered past as hub of Britannia Major, of the Anglian kingdom of Deira, Danish capital...

The Romans established Eboracum as a legionary fortress, later to be enlarged as a crossroads of the north. Roads ran westward to Luneceaster, the Anglian name for another Roman fort, south-eastward to Lindum (Lincoln), south-west to Deva (Chester). Constantine was declared emperor here before leaving to sort out Rome's problems very early in the 5th Century. Eboracum was abandoned.

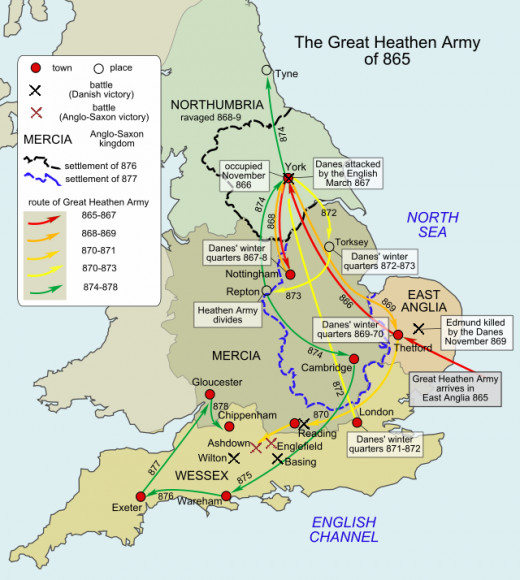

The Aengle came from the latter 5th Century onward. The Roman governor's palace was re-occupied and modified, and Eoferwic - as the city was now called - prospered as a trading centre, from King Oswald's time also a Church centre. By the 7th Century there were two kingdoms jockeying for superiority north of the Hymbra, the Humber. Northanhymbra was at times one kingdom - under Oswald and his brother Oswy for example - at other times at odds across the Tese, the Tees. When the Danish leaders Halvdan, Ubbi and Ivar came with their army - the 'micel here' in the Chronicles - to avenge the death of their father Ragnar Lothbrok Norhanhymbra (Northumbria) was fragmented with Aella as king in Bernicia and Osberht as king in Deira, the southern half of Northanhymbra when the territory was a single kingdom. Osberht was killed in battle in AD 866. A special 'treat' awaited Aella for the killing of their father in the snake pit. For him they reserved the 'Blod Erne' (Blood Eagle), whereby his ribs were prised loose and pulled back through his skin to resemble the appearance of an 'eagle' in flight. Those of his subjects made to witness the execution who did not faint would have been in no doubt as to what wyrd awaited them if they crossed Halvdan.

A 'puppet king' was appointed. In trying to re-take the city - now Jorvik - the Northumbrians were beaten badly the year after. In AD 876 Halvdan returned after raiding in the south, and 'took the reins'. His followers were given land around Jorvik but his rule did not last. He was killed in Ireland in AD 877. Little is known of his brothers after that, but by and large they were slain in battle against Aelfred's West Seaxe (Wessex). Of his successors even less is known aside from their names. Danish rule was threatened by Irish Norse influx to north-western Northumbria and Cumbria - then under Scots' rule. They had been displaced by Dyflin (Dublin) Danes, thrown out in AD 902. Three Danish kings and several chieftains were killed in a defeat at the hands of Wessex and Mierca (Mercia) at Tettenhall in AD 910, paralysing the kingdom. Jorvik fell to an Irish-Norse king Ragnald in AD 911. He lost power and returned in AD 919, ruling until dying in AD 921. Irish-Norse hold on Jorvik was fragile, and in AD 927 they were driven out by the Wessex king Aethelstan, grandson of Aelfred. This was the advent of the fledgling kingdom of Aengla-land (England). Trying to re-take Jorvik proved disastrous for Olaf Guthfrithsson. The Danish king of Dublin and an alliance of Scots, Strathclyde Britons and Welsh was defeated by Aethelstan at Brunanburh. The site of the battle has been put near the Wirral and in southern Yorkshire, but no-one can agree on its exact location.

Aethelstan died in AD 939. Olaf came back and not only re-took Jorvik but took Northumbria and the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw (Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford) as well. However Jorvik was back in Aenglish hands by AD 944. In AD 948 Eirik Haraldsson, nicknamed 'Blood-axe', fled Norway for the killing of his brothers who were to have ruled with him, and took Jorvik. His reign did not last long, threatened as he was alternately by Olaf Sigtryggson (sometimes said 'Sihtricsson') of Dublin and Eadred, the king of the Aenglish. Eirik was ousted and killed on Stainmore Common in AD 954. Rule by Aenglish kings was restored, yet they were wary of of Jorvik's loyalty to Scandinavian kings. Earls and archbishops were recruited in Wessex to enforce their kings' authority. A Norseman, Eirik of Hladir was appointed Earl of Northumbria for a short time by Knut, and then replaced by the Dane Siward, who held the earldom until his death in AD 1055. As Siward's older son Osbeorn had been killed fighting the Scots king MacBeothen (MacBeth. He was real but not as black as Shakespeare painted him), and his younger son Waltheof was too young to take over the often violent and always difficult Northumbria, the earldom was given to Harold Godwinson's younger brother Tostig. at times resented for being a southern outsider, Tostig was nevertheless half Danish through his mother Gytha, but by this time the Anglian nobles had the upper hand and Tostig was finally ousted, to be replaced by the Mercian earl Eadwin's brother Morkere in AD1065. Tostig 'sold' the idea of an invasion to Harald Sigurdsson, 'Hardradi', who harboured notions of taking Eadward's kingdom from King Harold according to an agreement between his nephew Magnus and the Danish Harthaknut. Harald 'Hardradi' occupied Jorvik briefly before leaving eastwards and being defeated alongside Tostig at Staenfordes Brycg (Stamford Bridge) on the River Derwent to the east of the city.

A rebellion that began in Dunelm (Durham) in AD 1069 spread to Jorvik, The aetheling Eadgar came to the city with the Northanhymbran nobles, the two wooden castles destroyed and many Northmen* (Normans) slain. He was forced to return to Scotland when William I hastened northward from Lindcylne (Lincoln), and much of the land around the city was razed in the 'Harrying of the North' (rated in Domesday as 'waste').

Archaeological excavations at Coppergate near the river Ouse show Jorvik prospered anN grew. By AD1000 the population had risen to 10,000. It was a large city by many standards of the time, second only to London in the whole of Britain. The division of a large part of the city into regular sections and a grid of streets at the onset of the 10th Century is indicative of planning. The Roman walls were restored and lengthened during the Viking Age. The Scandinavian kings had the silver content of the coinage increased (with both pagan and Christian symbolism) and promoted trade to increase revenue. Strong trade links were forged with Frisia and the Rhineland. Fine goods came from as far away as Byzantium through middle-men. Viking Jorvik was a thriving crafts centre, too. Digs have produced evidence of glass-making, metal working, woollen goods, wood-, leather-, bone-, antler and jet-working.

Most of the Scandinavian settlement lay to the south of the old legionary fort, the later administrative and church centre. There was no break in the local governement functions, in fact the Vikings exploited the system. Jorvik's archbishops, Wulfstan I in particular, had a close, cordial relationship with the Danish kings. The last time Jorvik was re-taken by the kings of Wessex they did not eject the Scandinavian population. Although their loyalties leaned toward their own kind, they were largely assimilated into Anglian culture. Nevertheless the city kept its Anglo-Norse character until the Normans burnt down large sections of the city by trying to secure their wooden castles with moats and clearance of the field of vision from the castle walls. The cathedral of St Peter was burnt down with he rest when the fire got out of control, not to be rebuilt for almost a century. Later these castles were rebuilt in stone and the Scandinavian character of Jorvik disappeared.

York emerged a cosmopolitan city in later mediaeval times, a crossing point for road and river again, and from the early 19th Century a rail centre with the 'Railway King' George Hudson its twice-elected lord mayor.

A day in Jorvik

English as was spoken here

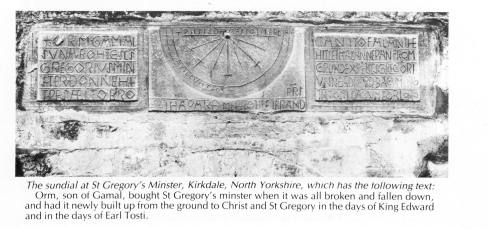

Little written evidence comes down to us about how and how early Old English and Old Norse were assimilated. There are carvings such as over the door at St Gregory's Minster in Kirkdale - on the southern edge of the North Yorkshire Moors between Kirbymoorside and Helmsley - which bear testament to men of Norse origin such as Gamal and Orm having memorials made using English as opposed to Norse. This was around the time Tostig Godwinson and Morkere were earls, before the Normans overran England.

Yet English was already changing. Many new words entered Old English from Old Norse, particularly East Norse (Danish), although some West Norse influence could be found from when Eirik Haraldsson 'Blood-Axe', was king in the late 10th Century.

Some of these words were very ordinary, unremarkable, 'they', 'their', ''them'. In York you can see the Norse origins of street names, 'Kopargata', Coppergate, where containers and barrels were made, hence 'cooper' for barrel maker. A 'gata' in the Norse meaning was a way or street, similar to Old English. In more modern English it changed meaning to being a gateway as we understand it now.

After the battle at Stamford Bridge nearby in the East Riding, so Snorri Sturlusson tells us in his 'Saga of King Harald Sigurdsson'. Styrkar one of his stallari (marshals) eluded the fyrdmen and came across a freeman or hold. He and the freeman talked and the freeman told him, 'I know you are West Norse (Norwegian) from the way you talk'. What dialect the freeman used is not known but he plainly knew one version of Old Norse from another, and from newcomers who came with Harald Sigurdsson.

By this time Old English and Old Norse in the north, and in Yorkshire especially, had been in the process of 'fusing' for at least a century and a half, borrowed words or forms of speech entering the Englishmen's vocabulary, Their offspring played together and learned new words or phrases from one another. By the time English became a written language again, long after the Normans had passed into history, much Norse influence surfaced and merged with the standard Middle English in dialect to survive into modern English in 'to take', 'to call', 'to die' even you use an Old Norse phrase. Describe fruit as 'rotten', a man as 'rugged', a field 'flat', a space 'tight' there it is again. Speak of eggs, freckles, keels or kids, skirts or steaks and these are words or forms thereof that entered into English from the Old Norse spoken by settlers, warriors, traders.

Professor Julian Richards guides us through turbulent times, and times of great prosperity for Jorvik amongst other trading centres in early mediaeval England. At its height, the reign of Knut Sveinsson provided an impetus for trade across the known world, from Ireland to the deepest backwaters of Arabia and Russia

What did they eat?

Tame livestock:

Cattle were kept for dairy products and rearing young, bulls were kept either for breeding or meat. Young bulls or stirks were fully grown before they were sold for slaughter. Calves were not slaughtered for meat. Oxen were kept for hauling carts.

Sheep were kept for breeding and wool, surplus young rams or tups slaughtered for meat. Young were kept until they had been shorn at least once.

Swine were kept for breeding and meat.

Horses were not eaten in great quantities, being kept largely for hauling, riding, racing and breeding. Chickens were kept largely for laying and breeding, young surplus cockerels went for meat.

Geese were kept as 'guard dogs', for laying and breeding, and slaughtered at times of surplus, as with tame (white) ducks.

Wild livestock:

Hares were caught for meat (rabbits arrived with the Normans, supplied by King Alfonso of Aragon).

Game 'on the wing' was caught, largely black grouse, golden plover, wild waterfowl.

Deer were hunted around Eoferwic/Jorvik, as were wild boar, for the tables of the wealthy or nobility.

Marks on cattle or deer bones showed signs of being made by cleavers or small axes, smaller tools were used on sheep or pigs. As is the custom nowadays, meat was cut off the bone on cattle. The sheep and pigs were cut into leg and shoulder joints and chops. Often the skulls and foot bones from pigs were found in the remains of houses, so therefore brawn and trotters were popular standbys. Most cattle and horse bones were cut lengthwise to extract marrow. Modern butchers split the carcase down the back to extract marrow.

Aside from meat, most other parts of animals were used around the house. Knife cuts show animals were painstakingly skinned. An ox-hide, when the animal had outlived its use, was as valuable as the meat from its hide. Horn was used for making cups, for example, the skulls found their uses.. Bones were cut variously for different household uses.

Fish

Freshwater fish was obtained from the many rivers in the area, the Swale, the Ure, the Wharfe, Derwent and Aire, as well as from the Ouse, Foss and further afield the Humber: Salmon, Pike from upland lakes, Trout, Sturgeon and Eel.

Sea fish was netted between the Humber estuary and the Tees, and further out. Herring was the most common offshore fish.

Nets were commonly used for both freshwater and sea fish, rod and line might have been used in lakes or tributary rivers off the main courses. Some rarer fish were brought in, salted in barrels from across the sea.

By the 12th Century larger sea fish such as Cod and Haddock supplanted salmon and pike. Later Turbot, Conger Eel and Halibut were introduced into the diet. Herring remained a staple.

Fruit, grain and vegetables

Root vegetables and cabbages were available. The carrots on the market tended to be similar to turnips, not the orange kind we know (that were imported much later from the Netherlands). What we see now are the results of many centuries of plant breeding, what they had in Viking Jorvik were much smaller. Herbs were used to flavour what was available.

From nearby open land grain was used for grinding wholemeal flour. Oats were available for baking as well as for oatmeal or porridge.

Seeds and fruit stones tell of apples, plums, cherries. The most readily available fruits were sloes, from the blackthorn bush. They are used nowadays for jam flavouring. Then they might have been sweetened with honey. Barley was used for brewing ale

Honey and hops

Honey was used also to produce mead, a very sweet alcoholic beverage. Hops grew in local woodland that was used to flavour ale. It would be a long time, several hundred years, before hops were used on a larger scale, and then they were grown largely in the southern shires from the 17th Century.

Wild plants

Not only for food but also as dyeing chemicals, nettles could be used for washing hair or for the pot, other plants could be used for medicinal purposes such as Dock Leaves, Dandelions, Burdock (these are still in use to make a popular fizzy drink).

Source: JORVIK - Viking Life Information Sheets available by various authors from the Jorvik Centre on Coppergate.

Jorvik Viking Centre, Coppergate, York

Jorvik Viking Centre, Coppergate, York YO1 9WT

- Jorvik

Travel back in time to when Old Norse was spoken in the streets and stalls of York, see how they dressed, what they did for a living, how they lived and caroused

For a different look at York, try this page...

- TRAVEL NORTH - 41: A Look Around York

York, literally a fount of history. Constantine was made emperor here, the Danes made it their power base and trading hub, two castles were built here by William I, Richard III made it his capital