Frank Lloyd Wright and Lee Lawrie: How Two Artists Impacted mid-Michigan

A Comparison Between Two Artists Who Changed America and Touched mid-Michigan

Frank Lloyd Wright and Lee Lawrie were two of America's best known architects and architectural sculptors of the Twentieth Century. Wright was famous for his Prairie Style houses as well as epic commercial projects like the Johnson Waxworks in Wisconsin and Price Tower in Oklahoma, while Lawrie was best remembered for his contributions to outdoor sculpture. Such examples as Atlas in front of the International Building in New York's Rockefeller Center and The Sower atop Nebraska's state capitol in Lincoln are standout specimens. Both these men were famous for these and many other major commissions during their lifetimes and ever since, but what may surprise readers is that they did lesser known works too. In the mid-Michigan area, several examples of their prodigious output are preserved in our time, and we are the more fortunate for it. This article is concerned with listing their major national contributions, but also with illuminating some of these more obscure achievements on a local level.

Lee Lawrie

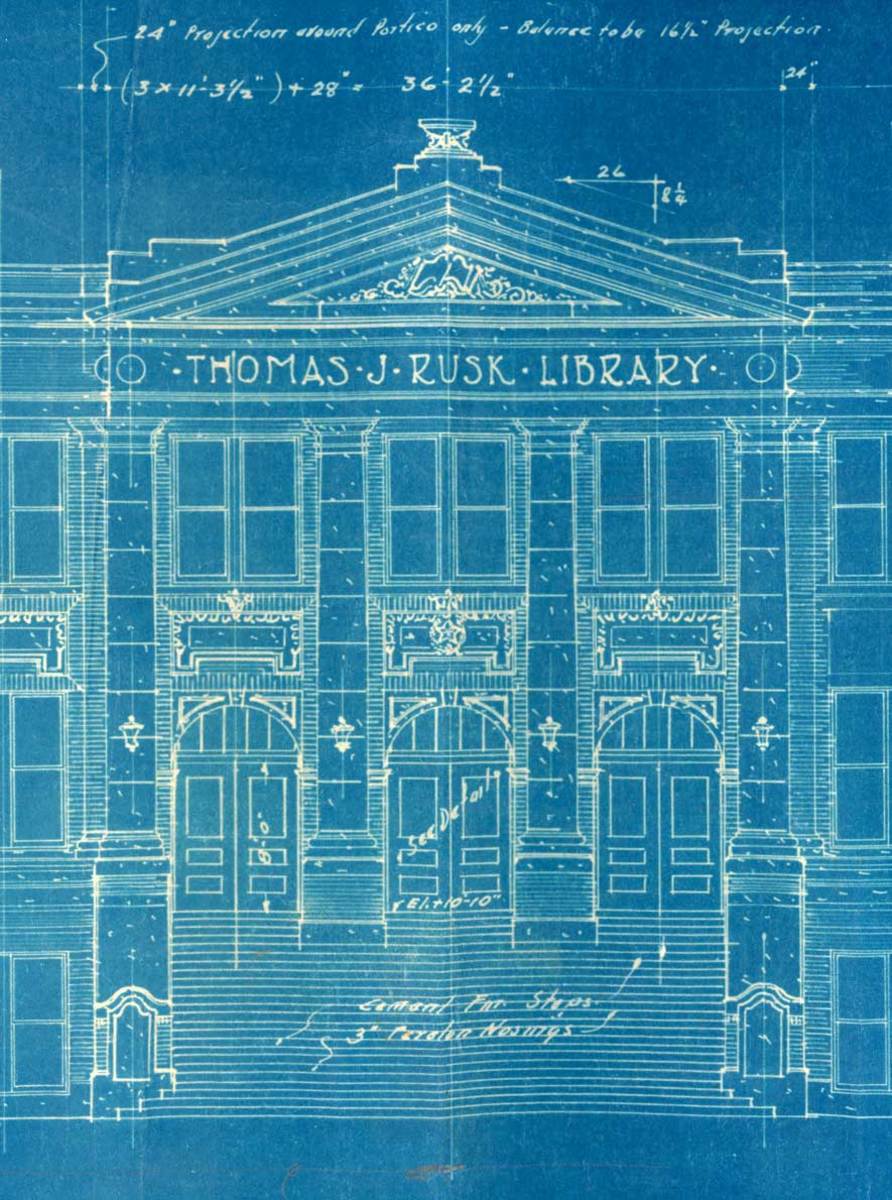

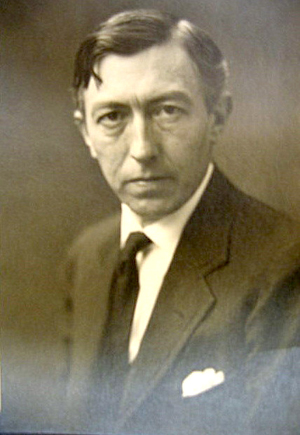

Lee Oskar Lawrie was born in Germany, and later migrated to the United States. His life actually paralleled that of Frank Lloyd Wright, the other subject of this article. Early in his career, he exhibited at the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904, under the guidance of Karl Bitter, a well-known architectural sculptor. He worked in large cities such as Los Angeles, Chicago and New York, but also in some remote places. He stands as one of the most seriously underrated sculptors of the Twentieth Century, and that is unfortunate, for his talent is starting only now to be fully appreciated. He also wrote books on his subject, and was something of a scholar of this fascinating area. In addition to his famous works in Nebraska and New York, he took time out to do work on the Beaumont Tower on the MSU campus, which was erected to replace College Hall, the first building at MSU and the site of the first classes in scientific agriculture to be taught anywhere in America. As with all his other works, it features a heroic cast and allegorical themes as applied to the American context. The mid-Michigan area is indeed fortunate to have had him as a guest sculptor, if only for a brief time.

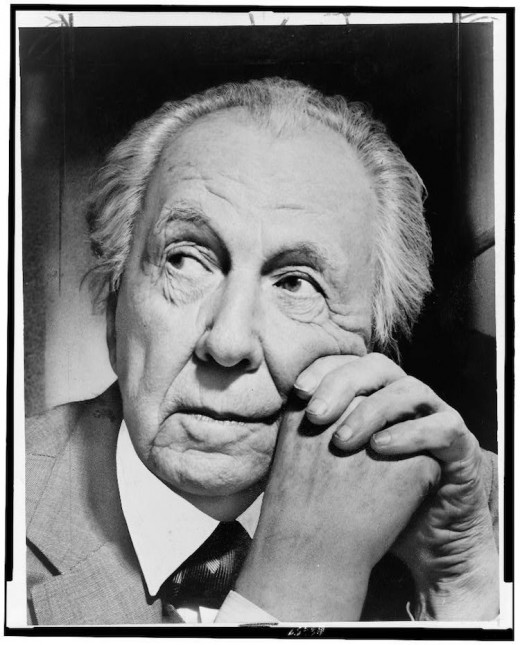

Frank Lloyd Wright

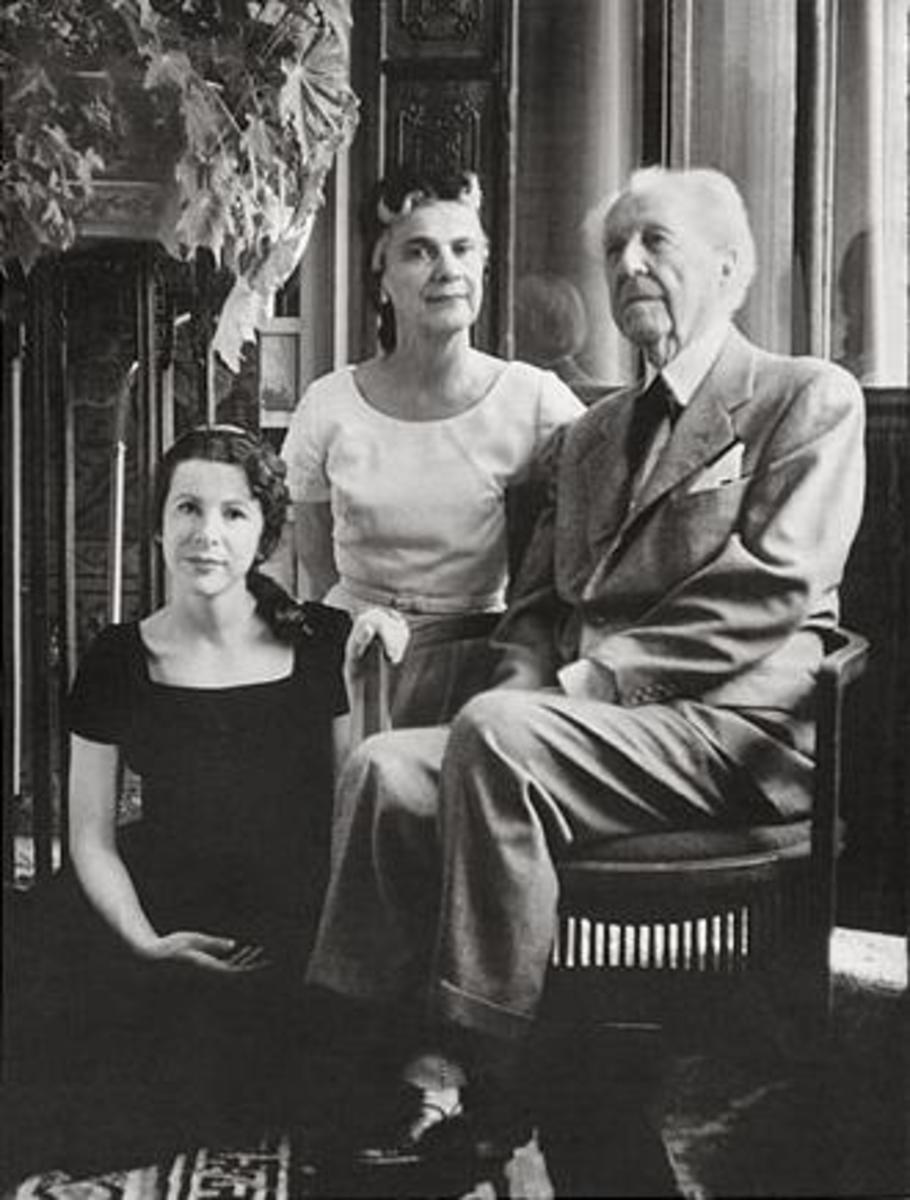

Frank Lloyd Wright is not easy to classify. He was probably America's greatest architect between the death of Louis Henry Sullivan in 1924, who gave us the dictum "form follows function" and the rise of the new postwar generation of geniuses who followed the Second World War. He almost towers over his age in the same way that Shakespeare, Beethoven, Rembrandt and Einstein dwarfed their peers and competitors. He worked equally well in residential or commercial ventures and made profound contributions to each genre. Such familiar structures as the Robie House in Chicago, Fallingwater in Bear Run, Pennsylvania and the Guggenheim Museum in New York--his only building in that city--come readily to mind. He also built a residence for himself in Wisconsin named for Taliesin, a Seventh Century Welsh poet. He later constructed Taliesin West, located in Arizona, which became a school for architects, and was continued by his wife after his death in 1959. At some point he came to Okemos, Michigan, a prosperous suburb east of Lansing and erected four houses at different times. Although not as famous or impressive as Taliesin or Fallingwater, they withstand at least favorable comparison with the Robie House and his other renowned Prairie Style residential structures, scattered across heartland America. Most of Wright's architecture is absolutely unique, and it is quite difficult to pin him down as representative of any particular style or school. Perhaps this is indicative of the true nature of this seminal architect, as well as genius everywhere.

How Do They Compare?

In any assessment of these two personalities, whose lives overlapped each other almost coevally in time, it is first of all necessary to understand their differences. Lawrie was an architectural sculptor, so his works are obviously smaller than Wright's, and it is sometimes required that one go out of the way to find them. They are certainly worth the detour, but Lawrie will always be handicapped by the fact that he did not engage in painting or architecture on a larger plane. Wright also did not pursue painting or sculpture to any serious extent, but he has the advantage of having larger structures as his legacy. This gives the pure architect a decided advantage in any comparison with a painter or sculptor. Having made this distinction, it is enough to say that the two of them made solid contributions to early and mid-Twentieth Century art, and helped to dispel the notion that America has nothing to offer the broader cultural world. Indeed, their widely scattered planting of works suggests that America has arrived as a civilized country and can lay claim to a New World corpus as impressive as any to be found in the old. Mid-Michigan is fortunate to have had their lives intersect here.