- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

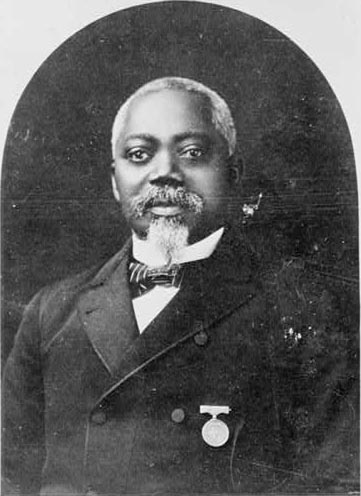

Medal of Honor Winner: William Carney

At the beginning of the Civil War African-Americans were not allowed to serve as soldiers in the Union Army. Abolitionists objected strenuously to this arguing that blacks should be allowed to enlist in order to fight for their own freedom. With Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 the status of African-Americans changed. From that day forth they were permitted to serve in the Union Army with the decree that “such persons [African-American men] of suitable condition will be received into the armed forces of the United States.”

The abolitionist Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts issued the first call for black soldiers early in February of 1863. At the time Massachusetts did not have many African-American residents but before they headed off to training there were more than 1,000 volunteers. Many of these men had come from outside of Massachusetts, including New York, Indiana, Ohio, Canada and even the slave states and the Caribbean.

These men formed the 54th Massachusetts Infantry and to lead them Governor Andrew picked 25 year old Robert Gould Shaw, the son of prominent Massachusetts abolitionists. Shaw had dropped out of Harvard to join the Union Army and had been wounded at Antietam. The story of the 54th Massachusetts is told in the 1989 movie “Glory.” Robert Gould Shaw is played by Matthew Broderick in the film and Denzel Washington won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his characterization of Private Trip.

William Carney Enlists

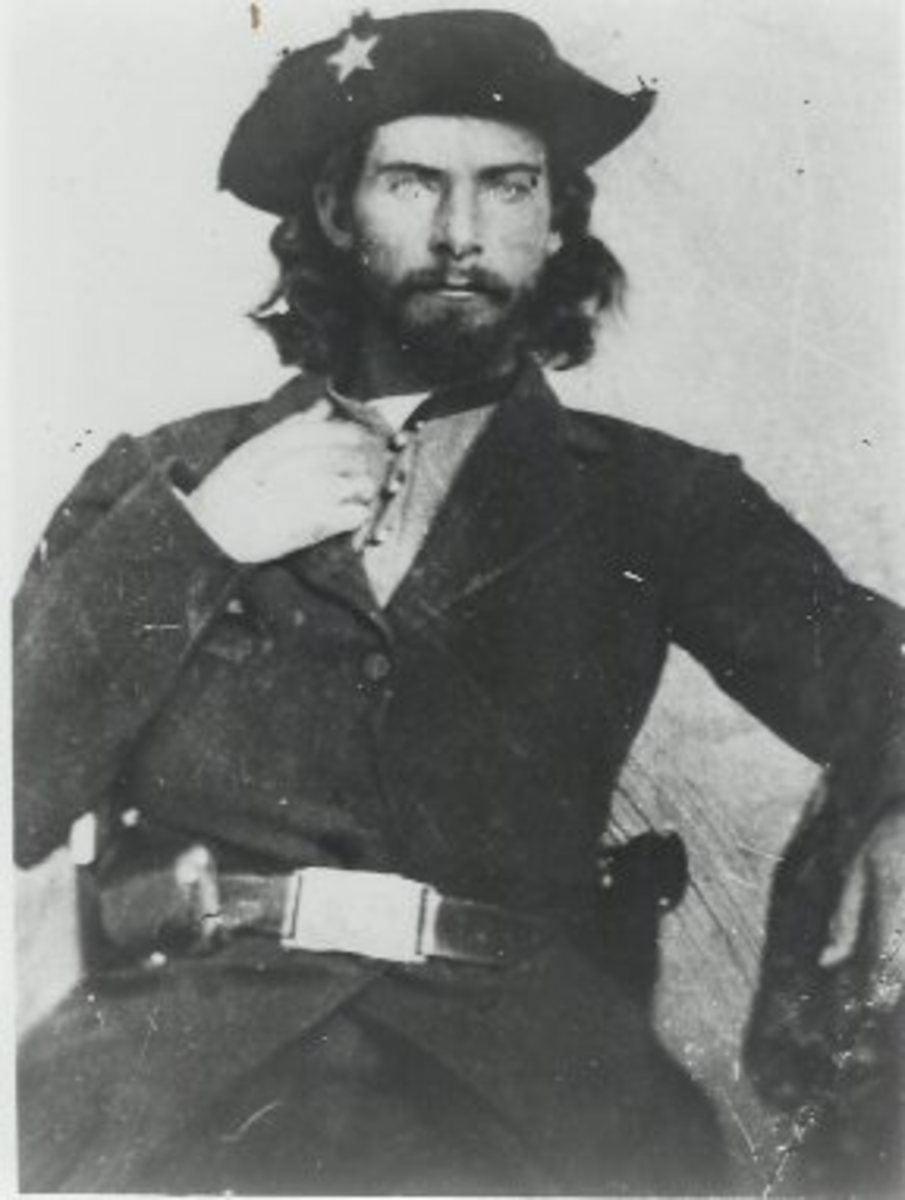

Born a slave in 1840 at Norfolk, VA., William Carney had followed the Underground Railroad to a new life in New Bedford, MA. At the age of 23 Carney heard the call for black soldiers and on February 17, along with 45 other volunteers from his hometown of New Bedford joined a local militia unit, the Morgan Guards. The Morgan Guards became Company C of the Massachusetts 54th and on March 4th everyone was assembled at Readville, Massachusetts to begin training.

Many did not believe the African-American soldiers would fight, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry was established to prove them wrong. The men involved encountered a great deal of prejudice in their training and supplies, military and otherwise. They had a lot to overcome simply to make it out of training and after only three months they were shipped into the heart of the action in South Carolina. The 54th would see action at Hilton Head, St. Simon’s Island, Darien, James Island and, finally, Fort Wagner.

Attack on Fort Wagner

Fort Wagner was located on Morris Island and guarded the entrance to the harbor at Charleston, SC. This harbor was vital to the resupply of the Confederacy and therefore of prime importance to the Union as a target. The 600 men of the 54th Massachusetts were to spearhead the assault from a strip of sand on the east side of the fort, facing the Atlantic Ocean.

The 54th was burrowed into a sand dune about 1,000 yards from Fort Wagner with the 6th Connecticut behind them. The fort was bombarded all day long by Union land and sea artillery. At nightfall the 54th was ordered to attack. They attacked in two wings of five companies each.

As the 54th advanced they were immediately hit by a barrage of canister and musket fire as well as shelling from the fort. The advancing men were being mowed down mercilessly, but they continued to advance. A bullet found the 54th’s color sergeant, John Wall, and as he began to fall Carney dropped his weapon and seized the flag.

With the primitive communications of that time, the flag was an important visual contact for troops and was used strategically as a rallying point. Carney forced himself to the front of the 54th’s assault where he soon found himself alone, at the fort’s wall, with the bodies of dead and wounded comrades surrounding him.

He decided to make his way back to Union lines, still holding the flag high. He was wounded twice, once in the leg and again in the arm. He ran into a soldier from the 100th New York, but he refused his offer to carry the flag and they struggled back to their lines together.

Upon reaching the relative safety of his own lines, Carney still refused to relinquish his hold on the flag until he came upon members of the 54th. Cheers greeted him as members of his regiment realized what had happened and Carney is reported to have said, “The old Flag never touched the ground, boys.” Carney promptly passed out from loss of blood and was removed further to the rear to receive medical attention.

During the battle, Company C of the 54th Massachusetts was able to, for a short time, capture a small section of Fort Wagner. The 54th suffered 272 killed, wounded or missing out of the 600 in the battle. Colonel Shaw was among those killed. Totally the Union lost 1,515 men of an assault force of 5,000. The Confederates suffered 174 casualties out of 1,800 defenders.

Aftermath

Although their attack was repulsed and they ended up having to lay siege to the fort it was a successful engagement for the Union. After two months of siege the Confederates abandoned Fort Wagner. More importantly however, the 54th was widely hailed for its bravery under fire. Their heroism brought about wider acceptance of African-Americans as soldiers and encouraged thousands of more blacks to enlist. Lincoln himself noted the bravery of the 54th at Fort Wagner and its importance in the Union’s ability to finally secure victory.

William Carney recovered from his wounds and word soon spread of his unselfish actions. When his commanders heard what had happened he was promoted to sergeant. Because of his injuries he was discharged from the army on June 30, 1864.

Medal of Honor

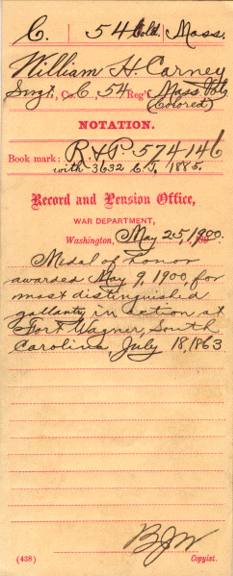

William Carney eventually returned home to New Bedford where he worked for the U.S Postal Service for 32 years before retiring. It was not unusual for acts of valor accomplished during the Civil War to go unrecognized for many years. Of the 1,520 medals awarded during that period for heroism more than half were not awarded until 20 years or more after the war. When William Carney was awarded the Medal of Honor on May 23, 1900 he was the last veteran of the Civil War to be so honored. Other African-Americans had been awarded the honor previously; however, since Carney’s actions on July 18, 1863 pre-dated all others he is considered the 1st African-American Medal of Honor winner.

His citation reads:

When the color sergeant was shot down, this soldier grasped the flag, led the way to the parapet, and planted the colors thereon. When the troops fell back he brought off the flag, under fierce fire in which he was twice severely wounded.

After retirement Carney was employed as a messenger at the Massachusetts State House. He was severely injured in an elevator accident in 1908 and died at home on December 9th. His funeral was well attended by state dignitaries and flags across the Commonwealth were flown at half staff. He was the first African-American and the first private citizen to be accorded that honor in Massachusetts history.

Today Carney’s heroism is depicted on the Saint-Gaudens Monument in Boston Common. The rescued flag is enshrined in Memorial Hall, Boston.