- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era

Napoleon: The Italian Campaign- Napoleon Strikes East.

Napoleon

A Quick Recap

A young Napoleon Bonaparte has inherited a disenchanted French army. An underpaid, starving and ill-equipped rabble of men, with some even bent on committing mutiny. Fortunately, a timely loan from a Genoese bank, used to acquire food and supplies, was enough to diffuse any talk of rebellion in the ranks. Bonaparte quickly imposed himself on his new army, using his knowledge, expertise and above all, his ability to rouse his troops with glorious speeches, telling them that Italy would give them everything they ever wanted. The War for Italy actually began on the 10th April, with the Austrians making the first move; however, Bonaparte repulsed the attack and went on to claim his first victory at Montenotte, the victory helped to create a gap between the allied forces of Austria and Piedmont, but there was still more work to be done, to achieve his conquering goal.

A Rethink

Austria’s defeat at Montenotte had been a bitter blow. The Belgian/Austrian general Jean Pierre Beaulieu, overall commander of the Allied forces decided to scrap his original plans and focus on joining his troops up with Argenteau’s Austrian forces and Colli’s Piedmontese forces stationed at Dego. Napoleon, meanwhile was already calculating his next move, studying his maps, he correctly guessed that his Austrian counterpart would not risk crossing the mountains that lay between him and Dego. Bonaparte could afford to discount any threat from Beaulieu for the time being; he made the decision to concentrate on his original objective, to knock Piedmont out of the war.

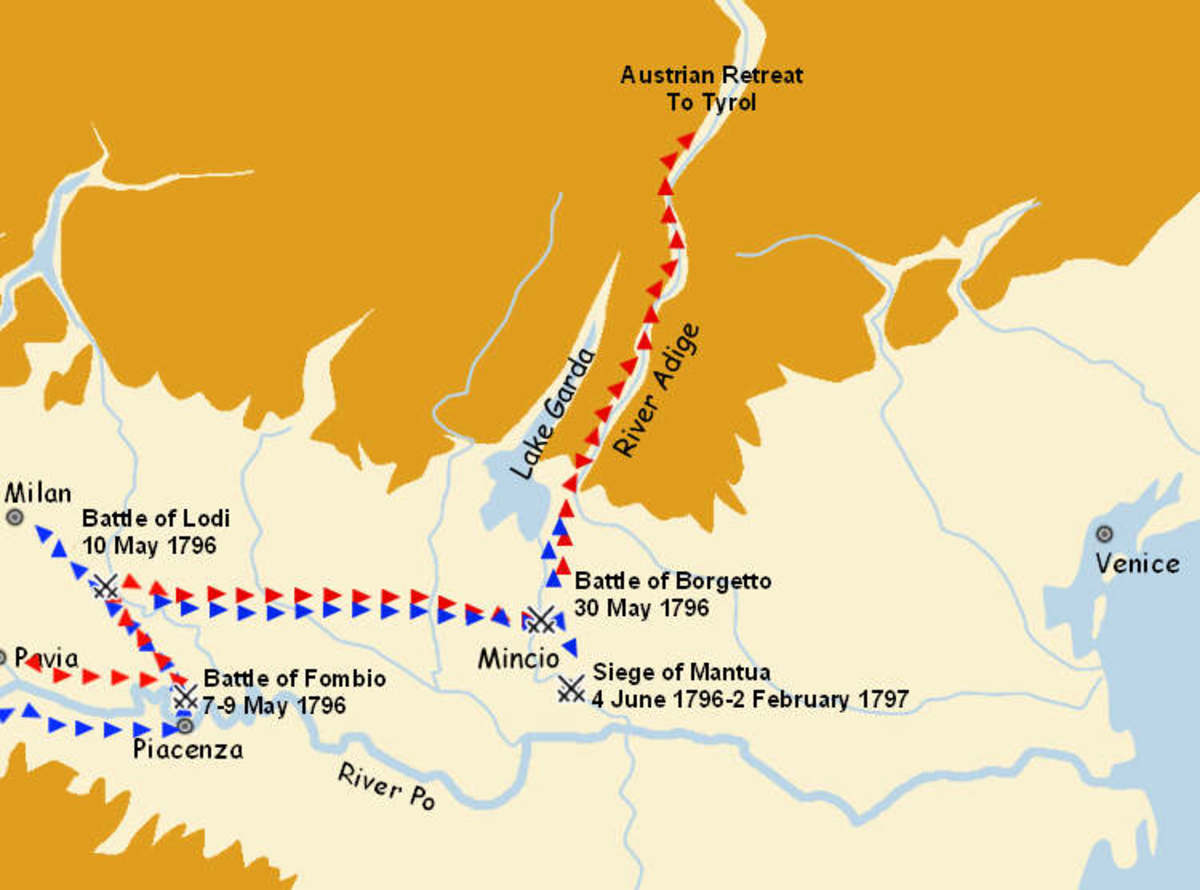

The Campaign Map

The Battle of Millesimo

Bonaparte sought to assemble an army to strike at Colli’s force of 20,000 men who had since moved away from Dego and advanced towards Millesimo to engage them. Bonaparte drew his troops largely from Augereau’s force of 10,000 incorporating them with elements of Massena’s and Serurier’s division to bolster the force up to 25,000, enough to take on Colli.

On the morning of the 13th April, the French under Augereau’s directive attacked the weak left flank of the Piedmontese just east of Millesimo. The attack was a complete success, but things hit a snag when Augereau and his men came across the ruined Cosseria Castle, currently holding 900 steely determined Austrian grenadiers, who were successful in all of the French attempts to dislodge them. This was an inconvenience because Bonaparte’s orders were that Massena could not fully engage the Austrians at Dego, until the castle was taken. Fortunately the setback was minor, as early the next day, the Austrians surrendered due to the lack of ammo, food and water.

Dego Today

The Battle of Dego

With Cosseria Castle pacified, Massena was now free to advance northwards up the Bormida valley towards the Austrians at Dego. No factual records survive, relating to the size of the Austrian force, but it’s estimated they numbered between 3000-6000; the numbers of troops available to Massena was double. Despite the clear disparity in numbers, the dogged Austrians put up a stiff fight, but eventually superior numbers won the day, and the French occupied Dego. In the aftermath of victory, the exhausted but jubilant French troops sought to reward themselves by running riot, looting and pillaging anywhere at will. Even Massena seemed to be indulging himself, as he committed a disappearing act, maybe to join in the looting or to seek out female company.

The Austrians would punish the French’s complacency, by attacking the next day, the 15th April under cover of a foggy dawn. In fact, this particular force, under General Vukassovich should have shown up the day before to reinforce the Austrians already present. But his orders had been poorly written, and he had arrived late. Nevertheless, the unintended Austrian error actually turned into a tactical masterstroke, as they literally caught the French with their pants down, driving them rapidly out of Dego, all the way back to where they started two days ago. Allegedly, according to Lieutenant Philippe-Paul Segur, Massena was caught in bed with a woman, and was forced to escape in his nightshirt.

The humbled French took some time to reorganise themselves and lick their wounds, but Massena was determined to re-take Dego, he was buoyed by the arrival of reinforcements sent by Bonaparte himself. The French attacked, once again the Austrians were outnumbered and the victory was just as easy as it had been two days before, but this time it was solid, Dego was now definitely in French hands.

The Battle of Ceva

Whilst the Battle of Dego raged; General Colli mustered a Piedmontese force on a patch of high ground near Montezomolo, so as to cover the fortress at Ceva. The French also made their move with Serurier advancing northwards along the Tannaro River valley headed for the fortress. Fear soon gripped Colli; he assessed the French strategy and decided to fall back to Ceva, through fear of being cut off. Meanwhile Augereau began to approach from the east, occupying the now deserted Montezomolo. After resting for a night, he and his men moved off, proceeding north, then turning west in attempt to outflank Colli.

The town of Ceva, which now housed Colli’s troops was a fortress town situated at the southern end of the River Tannaro. Imposing city walls circled the entire perimeter of the town; Colli decided to deploy his men along a heavily fortified ridge that ran from the fortress to the hamlet of La Pedaggera, around four miles away. Augereau sent two French columns to assault the Piedmontese left flank, a third column was sent to attack the centre. Despite the sustained pressure and considerable losses, the Piedmontese held firm, repelling attack after attack.

As evening approached, Serurier arrived and camped down within sight of the fortress, threatening to target the thus far unaffected southern flank. Later that night, General Brempt, commander of the northern flank reported to Colli explaining that he would be cut off if the French were to attack again. Despite the hard fought victory, the mood among the generals was low, they wished to retreat. Colli summoned them all to a meeting to discuss options, they all agreed that the best course of action was to fall back west behind the Corsaglia River, towards Mondovi. Colli elected to leave one battalion to guard the fortress, while sending another northwest to Cherasco to discourage the French from attempting an attack on Turin.

The fortress was now, all but deserted; the small battalion surrendered on the 17th April, the French marched in. Napoleon wanted to pursue and harass the Piedmontese back all the way past Mondovi, to the city of Cuneo. The attack on Ceva had seen the French pay a heavy price in casualties, it wasn’t a victory, in the same way the previous battles had been. Even so, Napoleon still felt confident to open up a new line of communications stretching back along the Tannaro River valley, back to Ormea. Colli, and his Piedmontese army, now stationed near Mondovi, soon realised that by retreating northwest, he had cut himself off from his Austrian allies, effectively Mondovi would be where he would make his last stand, in order to hinder the French, he destroyed all of the bridges and erected a series of stone fieldworks.

Location of the River Tannaro

The Battle of Mondovi

Colli by now probably knew that he was fighting a losing battle; even so he formed his army in a defensive position along the western bank of the River Corsaglia, not far from where it flows into the Tannaro at Lesegno. Colli’s left flank was protected by the river, currently in flood, making crossing tricky. The front line of Colli’s army stretched from to the village of San Michele, which itself was protected by a series of fortifications on the La Bococca ridge.

Napoleon sent Augereau along the right hand bank of the Tannaro, whilst Serurier was to try to get across the Corsaglia. When Augereau reached the river, he made the painful discovery of the flooding situation, even worse; all of the bridges had been destroyed. The plan was now totally impossible to execute, Augereau’s men would play no part at all in the battle.

Meanwhile, Serurier proceeds with his attack across the river, but is stopped by cannon fire, protecting San Michele. However, to his left, a column manages to smash its way across the river at Torre, the vulnerable Piedmontese right flank conduct a hasty retreat, but are all captured before they could reach the sanctuary of the hills above the village.

Once again, the French experienced a loss of discipline, looting and pillaging San Michele at will, this gave the Piedmontese a chance to regroup and launch a counter attack. By the end of that same day, the French had been forced back across the river, although they retained a foothold at Torre. With the French now experiencing humiliation, both commanders paused to take stock of the situation, pondering their next move. Napoleon decided to carry out a renewed attack on the 22nd April.

However, Colli once again had retreat on his mind, and the day before Napoleon’s proposed attack, he saw fit to withdraw his men from the river and through Mondovi itself. Napoleon sent Serurier to pursue him, to try and force him to commit to another battle. Colli, soon realised that he could run no more, he turned and made his stand on a plateau that lay between Mondovi and Vicoforte, while his army engaged the French, his supply train made a quick getaway. The rearguard action was able to hold the French off until 4pm, but even that didn’t stop a troop of cavalry from threatening the Piedmontese retreat. Fortunately, the Piedmontese cavalry were aware of the danger and executed an efficient counter attack which vanquished the threat.

The French, after capturing Brichetto, were now free to advance onto Mondovi itself. Colli had left a small garrison behind, but there was no way they could stand up to the French. Napoleon’s army arrived and entered into negotiations with the town governor, who attempted to assist Colli’s retreat by deliberately stalling the process, but relented when the French began firing on the town at 6pm. As part of the surrender terms, Bonaparte forced the authorities to provide food to his hungry soldiers, in exchange for not sacking the town.

The Battle of Mondovi

Aftermath

Colli and most of his army, did manage to escape the clutches of the French, but they were finished, and of no threat to Napoleon. As for the little general, the victory at Mondovi saw him leave the mountains behind, and his army marched onto the foothills of the Po Plains. The unrelenting general now targeted Turin, and he would have probably taken it, if not for the intervention of King Victor Amadeus II of Sardinia asking for peace terms, the French authorities agreed, and on the 28th April 1796, the Armistice of Cherasco was drawn up. The terms of the deal, saw Piedmont come under the control of France, all of its fortresses surrendered to the French. In just three weeks, Napoleon had succeeded in knocking Piedmont out of the war altogether, now he was free to turn eastwards, cross the plains and take the war to the Austrians.

More to follow:

References

http://www.historynet.com/general-napoleon-bonapartes-italian-campaign.htm

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/campaign_napoleon_italy_1796.html#1

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/people_napoleon.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon_Bonaparte

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_millesimo.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_dego_1796.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_ceva.html

http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_mondovi.html

Boycott-Brown, Martin,The Road to Rivoli, Cassell & Co, 2001

Chandler, D,The Campaigns of Napoleon, Macmillan, 1966

Dwyer, P, Napoleon- The Path to Power 1769-1799, Bloomsbury Books, 2008

Fiebeger, G. J,The Campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte of 1796–1797, US Military Academy Printing Office, 1911

Foreman, L & Phillips, E, Napoleon’s Lost Fleet, Discovery Books, 1999

Grant, R.G, Battle, Dorling Kindersley, 2010

Rothenberg, Gunther, The Napoleonic Wars, Cassell, 1999