Otavalo Indians and the Path of Globalization, Part 2 of 3: The History

Ancient History in the Andes

Artifacts dating back 10,000 years have been found in the Northern Andes, but theories about where the first people who settled the region come from are conflicting. What archeologists are sure of is that the settlements of the Otavalo valley reached a high degree of social organization well before Inca times, with traditions of textile weaving and commerce extending far back into their history. The area has long been a crossroads for trade with the people of the jungle lowlands and up and down the Andes.

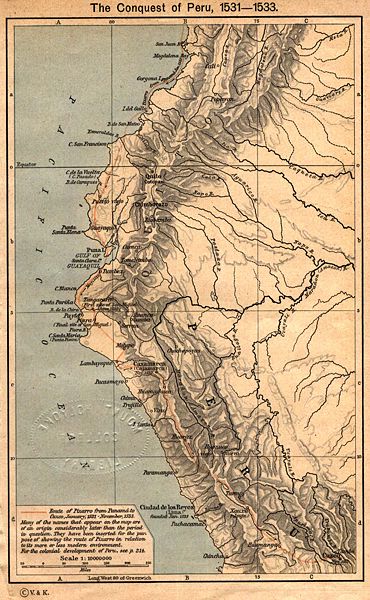

The Incas were attracted to the area because of its high trade volume and potential for wealth, but upon invasion in the 12th century they were confronted with an organized resistance by the Otavalos and other local groups that lasted for 17 years. When the Incas did finally colonize the region, they brought their Quichua language there, which has remained with most Andean groups of the Ecuadorian highlands to this day.

The Andes is one of the most textile-oriented areas in the world, and cloth has historically been important throughout the region. Since pre-Inca times, textiles have conveyed political and cultural messages and the Incas offered finely woven textiles as sacrifices for deities and ancestors and bestowed them as gifts and symbols of honor. So, it seems fitting that the Otavalos would go on to gain their wealth through textile production in modern times.

Read the First Part of this Hub:

- Otavalo Indians and the Path of Globalization, Part 1 of 3: Introduction

The Otavalos are one of the most prosperous indigenous groups in the Americas, and are well-known throughout the world. They've embraced globalization without losing their cultural roots, and this article introduces them.

Spanish Colonization

With the Spanish invasion of the 16th century, the communities of the Northern Andes once again maintained an organized resistance, but eventually gave in to the agression. Their population was decimated by new diseases as well as the forced labor they endured under the Spanish, who took adavantage of the high degree of social organization of the region, which already included the payment of taxes to the government.

The Spanish established brutal systems of forced labor in sweatshops and the wasipungu*. In colonial times, the mass production of textiles involved debt-servitude and exploitation, and many indians were forcibly removed from their land and resettled in large haciendas**, where they worked in exchange for the right to live on the hacienda owner’s land and farm their own small plot.

In the 1640’s, there were fourteen sweatshops in the Otavalo valley, in which the Indians worked to pay tribute. Little by little, Otavalo evolved from a general province to a township into which many missionary orders were sent, until, in 1829, Simón Bolivar officially declared it a city.

By 1900, haciendas were in control of most arable land, and there was a slight outmigration by Otavalos into higher altitudes with less fertile soil. However, individuals and communities continued to resist the privatization of communal landholdings, holding on to the Andean tradition of the ayllu***. The hardships of colonization were held in the communal memory of the Otavalos, who maintained their traditional practices of weaving and commerce through the centuries.

Andean Indians and Scottish Tweed

The popular story of how commerce to non-Indians began takes place in 1917, when there was a scarcity of English products in Ecuador due to World War I. The owner of the most powerful hacienda in the area gave her Quito-based son-in-law a poncho as a wedding gift. He was so impressed by its workmanship that he requested that the weaver, José Cajas of a small village of Otavalos called Quinchuquí, create an imitation Scottish tweed called casimir with a European loom and market it to the white/mestizo population in Quito. The initial success of casimir opened up a new market for the Otavalo and initiated a process of communiy specialization in handicrafts. Different towns and villages became known for baskets, hats, cotton or wool cloth, leather, and more, marking the beginning of the Otavalos’ habit of translating foreign ideas into significant revenue sources.

The Saturday Market

Between 1935 and 1940, the weekly Saturday market in Otavalo had expanded so that the main plaza of the city was utilized for the market as a local and non-tourist event, where handicrafts, food, and livestock were sold together. In the 1940’s, Otavalos selling meat or cloth in Tulcan began to cross the border into Colombia to sell textiles. After World War II, the artisans who had specialized in casimir were unable to compete with rebounding European and North American producers. This decline in the sale of wool coincided with aid projects that began to develop in the 1950’s and 1960’s, such as the Andean Mission, the International Labor Organization, and Peace Corps, as well as the growth in tourism of the same decades, all of which helped to move textile production toward its present state.

used Lynn A. Meisch's books to write this article.

Commercial Success

Two extremely successful contemporary products, tapestries and sweaters, were introduced by foreignors so that the Otavalos could apply their traditional skills to these foreign ideas and turn them into a booming industry. Tapestry weaving was introduced in the 1950’s by Jan Schreuder, a Dutch artist who saw no future in the casimirs. The prominence of this new product encouraged migration into the rest of South America throughout the 1950’s. Through travel, Otavalo merchants and their families gained a greater sense of foreign and upper class wealth, which was heightened by their own poverty and led to even more determined retail in the 1960’s, when they expanded into the Caribbean and the United States, and a sizeable Otavalo community was established in Bogotá.

Economic Prosperity Leads to Political Power

Increased income and international presence paid off. 1964 was an important year for all of Ecuador’s indigenous people, marking land reform and the introduction of the most successful product the Otavalos had dealt with. The law of agrarian reform was passed in response to increased indigenous activism and protests, which put international pressure on the government to abolish the oppressive wasipungu. 180,000 hectars of land were redistributed over the next 20 years, freeing indigenous people across the country from an endless state of economic inhibition and opening up new opportunites to increase their income. A Peace Corps project of the same year introduced sweaters to the Otavalo as a potential income source, which have today grown to be one of their best-selling products across the globe.

The 1970’s were also landmark years. Following the Ecuadorian petroleum boom, thousands of impoverished indigenous from the highlands emigrated to the petroleum rich Amazon region. Eager to modernize the country with its new wealth, the Pan-American highway between Colombia and Quito was paved, and new bridges were constructed, improving access to Otavalo. In 1973, the city paved the Plaza Centenario and constructed concrete kiosks for vendors, establishing Otavalo as a seriously market-oriented city. In the 1970’s, full-time weaving and merchandising blossomed as occupations, taking the place of farming for many people. Now that the wasipungu and other repressive sysems were removed, the indigenous community began to organize and demand more rights, identifying with the liberation theologists of the Catholic church, who sympathized with land reform and other calls for justice. The 1970’s boom in sales and recent political gains raised Otavalos’ self-esteem and provoked a widespread tendency for international travel, especially to North America and Europe. Despite the OPEC oil crisis of 1973, which forced the government to accept neoliberal reforms resulting in growing disparities in wealth, the Otavalos expanded their export market, developing music as another important economic activity in the 1980’s.

Plan your trip to Otavalo, Ecuador

Despite Hardship, the Otavalos Expand

However, hardship followed the boom for most of Ecuador. Recession, hyperinflation, electrical shortages and rationing in the mid 1990’s, natural disasters including El Niño floods and volcanic eruptions, and the bank failures of 1999 all affected Ecuador’s economy profoundly. Corruption and instability became trademarks of the country after it famously plowed through ten presidents in eleven years. The decades long civil war in Colombia has also contributed to increased immigration abroad, as merchants lose sale to their neighboring country, and the dollarization of the economy in 2001, while cutting inflation, also caused a dropp in sales to Colombia by raising the price of Ecuadorian goods and reducing the income from dollar remittances abroad.

Impossibly, throughout years of hardship, the Otavalos’ prosperity has increased. They are constantly looking for ways to keep up with themarkets, modernizing their factories and taking on new export clients. Otavaloswho market their products and identity abroad have lately migrated to Australia and Asia, especially South Korea. There are small communities of Otavalos in most countries, with some cities, such as Amsterdam, hosting their own “Little Otavalo”, communities of over a thousand expatriates.

Useful Terms

White/mestizo- term I use to describe the dominant culture of Ecuador and most of Latin America consisting of strongly hispanicized cultural traits and the Spanish language, with more subtle indigenous and African influences. People of any national or racial descent can identify with this cultural group, though in Ecuador is consists mostly of mixed Amerindian and white mestizos.

wasipungu: A system of debt servitude in which Indians became permanently attached to large, landed estates, caught in a serf-like form of debt repayment that was almost impossible to escape from.

Hacienda: Large, landed estate, usually used to describe a type of plantation, mine, or factory.

Ayllu: Basic social unit of Inca and pre-Inca life that consisted of extended family groups or neighboring settlements that shared a plot of land which every individual farmed for the benefit of the communiy. These organisations were mostly self-sustaining, but also relied on a centralized storehouse to which many ayllus contributed that was meant to provide security in the case of an insuffeicient harvest or a natural disaster. The system of the ayllu still exists in the Andes, though it has been very diminuished.

Read the Rest of This Hub:

- Otavalo Indians and the Path of Globalization, Part 3 of 3: Maintaining Cultural Identity

How the Otavalo Indians maintained their traditional culture while developing a global presence.