- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

The American Civil War: Battle Of Antietam

The Bloodiest Day In American History

Introduction

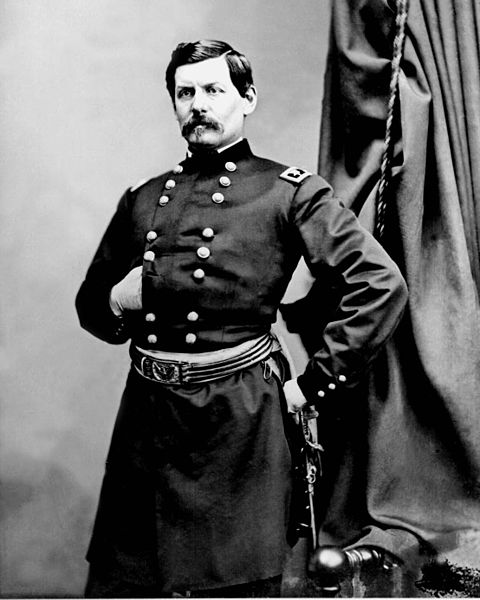

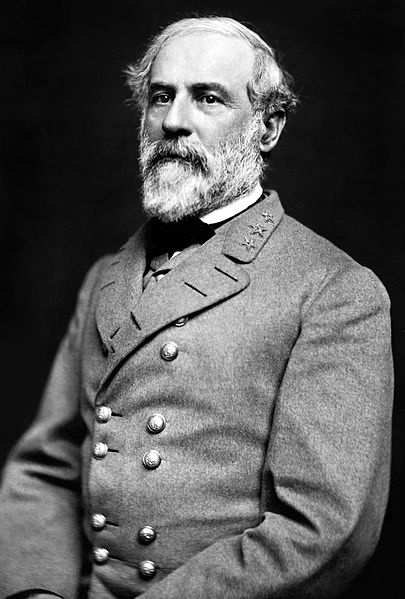

The summer of 1862 was one of frustration in Washington DC. Sixteen months after the first shot of the American Civil War had been fired at Fort Sumter, the Union was still without a major victory in the Eastern theatre. The Peninsula Campaign, its objective the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, had been repulsed during the Seven Days’ Battles in July and July. A humiliating defeat at Second Manassas (Bull Run) followed at the end of August. Desperate to restore order and morale among the dispirited troops, President Abraham Lincoln reinstated General George McClellan to overall command. A superb organiser, McClellan was the architect of the Army of the Potomac, but he was also cautious and devoid of initiative on the battlefield. On the other hand, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, always hungry, often without shoes, nevertheless displayed the spirit and dash that only victory could bring. Its commander, General Robert E. Lee had displayed tactical brilliance and defeated the enemy at nearly every turn. Only a week after Second Manassas, he crossed the Potomac River and invaded the North.

Lee's Audacious Gamble

Lee reckoned that an expedition into Maryland and Pennsylvania could accomplish a great deal, both militarily and politically, for the beleaguered South. It was believed that Southern sympathisers in Maryland would rally to the rebel army, providing food, supplies and new recruits. The Confederates could also live off the rich farmland of southern Pennsylvania, destroy the railroad bridge across the Susquehanna River and threaten the state capital at Harrisburg. A victory on Northern soil would allow Lee to menace Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, DC. Perhaps most important of all, such a victory might bring formal recognition and much needed assistance from the governments of Great Britain and France. Lee further realised that the capacity of the Union to wage war was virtually limitless. The Confederacy had seized the initiative. Now, it had to utilise that initiative to its fullest.

Following the abortive Peninsula Campaign, McClellan had been demoted in favour of General John Pope, who had established and quite probably embellished his reputation as an Indian fighter in the West. During the campaign of the Second Manassas, Pope may have been willing to fight, but Lee and his capable subordinates James Longstreet and Thomas J. ‘Stonewall’ Jackson made him appear a rank amateur. Confederate cavalry raided Pope’s headquarters at Manassas, stealing his dress coat and $350,000 in cash. Then Longstreet and Jackson completed the rout on the old battlefield of Bull Run. When Lincoln swallowed his pride and recalled McClellan, the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac gave a mighty cheer. To a man, they loved ‘Little Mac.’ This time, though, McClellan did not march his troops in Virginia. He headed northwest into Maryland to intercept the invading rebels.

The Maryland Campaign

The Respective Commanders

The Campaign

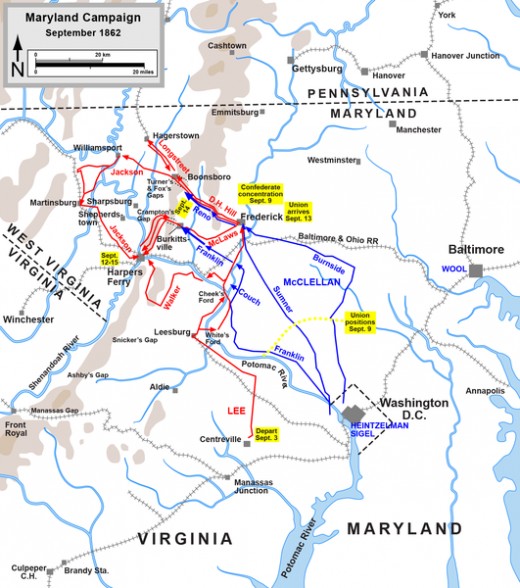

As the Confederates advanced towards the town of Frederick, Maryland, the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry lay between Lee and his supply base at Winchester, Virginia. It might also sever his line of communication with Richmond via the Shenandoah Valley.

Discounting one of the principles of command, Lee divided his army in the face of an enemy of superior strength and sent Jackson to capture Harpers Ferry. Lee counted on McClellan’s caution, confident that Jackson could complete his task and re-join the main army before Union troops arrived in overwhelming numbers. By the 12th September, the entire Army of Northern Virginia could concentrate at Hagerstown, Maryland, and continue into Pennsylvania.

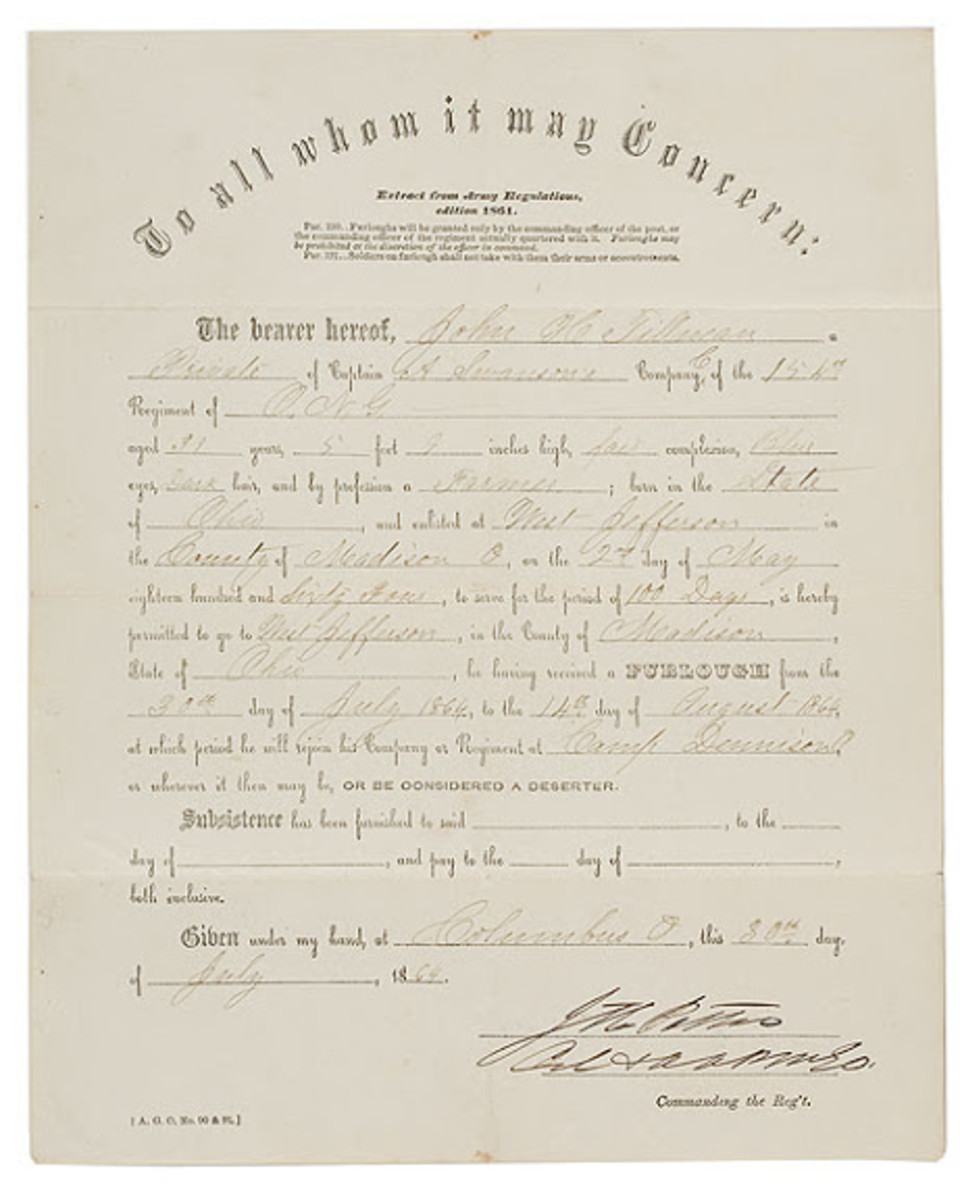

While Jackson dealt with Harpers Ferry, Longstreet’s corps headed for Hagerstown on the 10th September. Three days later, as the bulk of McClellan’s army reached Frederick, a private from an Indiana regiment noticed an envelope lying on the ground. Inside there were three cigars and a copy of Special Order 191, which Lee had issued on the 9th September. The order detailed the dispositions of Confederate troops, and it was soon in McClellan’s possession.

Lee’s entire army was now in great peril. If McClellan moved swiftly eastward through the passes in South Mountain, he might interpose his army between Longstreet at Hagerstown and Jackson at Harper’s Ferry. His larger force could then crush these separate elements one at a time.

Unaware that Special Order 191 had fallen into McClellan’s hands, Lee had already begun to worry that the capture of Harpers Ferry was taking too long. He knew that McClellan was at Frederick, and the movement of the Union force, although ponderously slow, still proceeded at a disturbing pace. Even with the knowledge of Lee’s predicament, McClellan wasted several precious hours and did not start toward the South Mountain passes in earnest until the morning of the 14th.

Events now seemed to be developing rapidly, and Lee could feel his control of the situation slipping away. He ordered Longstreet to send troops from Hagerstown to defend Turner’s and Fox’s Gaps and Jackson to dispatch a force from Harpers Ferry to guard Crampton’s Gap further south. Their delaying actions could buy precious time for Lee to gather his scattered forces. Inevitably, though, McClellan would force his way through the gaps, and Lee issued orders on the night of the 14th to abandon the Harpers Ferry positions in preparation for a general withdrawal to the safety of Virginia.

In the early hours of the next day, as Union troops marched ever closer, Lee finally received some good news. A message from Jackson stated that Harpers Ferry would fall on the morning of the 15th. Lee cancelled his original order and instructed his forces to concentrate near the town of Sharpsburg. Longstreet moved, and Jackson rapidly departed Harpers Ferry, leaving General A.P. Hill’s Light Division to deal with captured booty and nearly 12,000 Union prisoners.

Battlefield Dispositions

Where Was The Battle Fought?

Battlefield Location

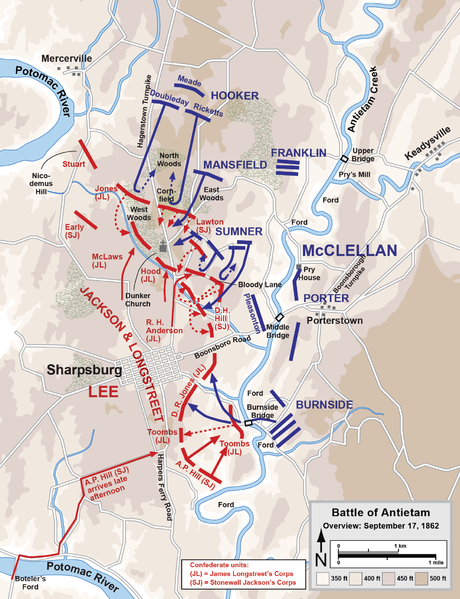

The above map shows where America's bloodiest battle was fought. Incidentally the battle is sometimes referred to as the Battle of Sharpsburg.

The Order Of Battle

- Antietam Union order of battle - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

And the Wikipedia page showing the Union order of battle. - Antietam Confederate order of battle - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Wikipedia page showing the Confederate order of batte.

Dispositions

Believing he might yet salvage his campaign, Lee chose to make a stand along a low ridge which overlooked Antietam Creek. General J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry screened the left flank of the Confederate line, which was anchored by General John Bell Hood’s division on a forested area called the West Woods and around a whitewashed Dunker Church, which stood adjacent to the Hagerstown Turnpike. General D.H. Hill placed five brigades in the rebel centre, across the Boonsborough Pike. The division of General D.R. Jones held a mile of the Confederate line, which ended along high bluffs on the west side of Antietam Creek above the lower bridge, one of three stone spans which crossed the stream. By the evening of the 16th, most of Jackson’s troops had arrived from Harpers Ferry and doubled the size of Lee’s force to about 36,000.

At midday on the 15th, McClellan had assembled 75,000 troops east of the Antietam. Both sides had placed artillery on the surrounding high ground, and sporadic firing occurred on the 16th, while McClellan refined his plan of attack. Two army corps, under Generals Joseph Hooker and Joseph K.F. Mansfield were placed on the Union right and ordered to make the initial assault, with the corps of Generals William B. Franklin and Edwin V. Sumner available to exploit any significant gains. General Fitz-John Porter’s corps took up positions in the Union centre along the Boonsborough Pike, and the corps of General Ambrose Burnside was positioned on the left near the lower bridge. McClellan’s plan was simple. If Hooker and Mansfield made significant gains, Burnside would attack the Confederate right flank and perhaps push on into the town of Sharpsburg. Finally, Porter’s troops would assault the Confederate centre in support of either flank attack. In typical fashion, McClellan had squandered opportunities to attack the much smaller Confederate army on the afternoon of the 15th and again on the 16th. When battle was finally joined on the 17th, Lee was able to utilise his interior lines. Shuffling reinforcements to areas of heavy fighting, he stymied several Union breakthroughs. McClellan failed to coordinate his attacks and committed his reserves in a piecemeal manner, negating his numerical superiority.

The Battle Of Antietam On Film

Dunker Church: Then And Now

Bloody Lane

Highly Recommended Links

- Antietam Eyewitness Accounts

More eyewitness accounts, this time from both Union and Confederate soldiers. - An Artilleryman At Antietam

Read the firsthand account of the battle, written by Lieutenant George Breck, a gunner with the 1st New York artillery. - Civil War Battle of Antietam

Watch an interesting animated history of the battle. - The Battle of Antietam Summary & Facts | Civilwar.org

The official Antietam website powered by the Civil War Trust, who dedicate themselves to saving Civil War battlefields.

More Battlefield Literature

The Battle

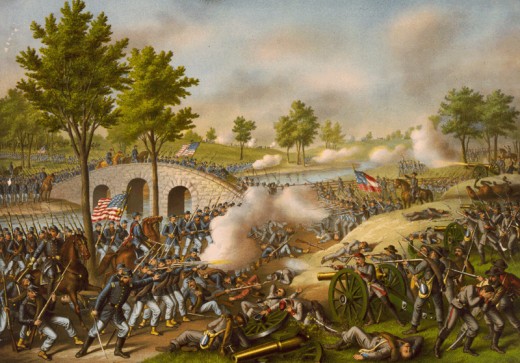

At first light, Hooker’s Federals advanced down the Hagerstown Turnpike toward the Dunker Church. Artillery fire tore great gaps in the ranks of the defending Confederates, and the focus of the savage fighting became a 30 acre field of head high corn owned by a farmer named David Miller. Relieved during the night by two brigades under General Alexander Lawton, Hood’s Texans were cooking breakfast when the fighting began. A desperate Lawton called for help, and Hood’s shock troops sent Hooker’s spearhead reeling back more than 400 yards. Both sides committed additional reinforcements and the dead and wounded began to pile up. Some accounts relate that the bloody cornfield changed hands up to 15 times.

More than 90 minutes after Hooker’s opening attacks, Mansfield assaulted the Confederates over the same ground. As his right was torn apart by Confederate artillery, Mansfield was mortally wounded. One Union division, commanded by General George Greene, managed to reach the rocky ground before the Dunker Church, but no other units appeared to take advantage of the gain, and Greene’s men were isolated and pinned down.

At approximately 9 am, Sumner himself led two divisions from the vicinity of the East Woods, about half a mile from the ragged Confederate line. In response, Jackson deployed reserves, some just off the march from Harpers Ferry and others transferred from the rebel right near the stone bridge, to spring a trap along the edge of the West Woods. During the march, the second Union division, under William French, lost contact with Sumner and veered away. A single division of 5000 men, commanded by General John Sedgwick, continued, stumbling into the trap set by Jackson. The crossfire of nearly 10,000 Confederate muskets cut down half of Sedgwick’s strength in a mere 20 minutes. Jackson counter-attacked but was repulsed by Sedgwick’s artillery. The third Union attack of the morning had gained nothing, and scores of dead and wounded littered the ground around the cornfield, the Hagerstown Pike and the Dunker Church. By 10 am, the Confederate left had held, battered but unbroken.

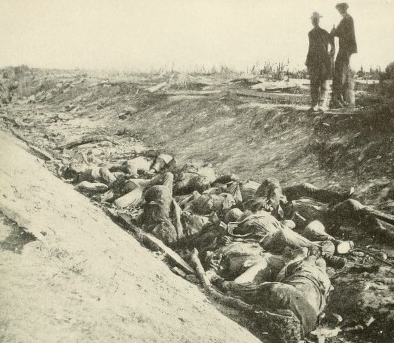

The fighting now shifted southward, where D.H. Hill had taken advantage of a sunken road, which had been worn down by years of wagon traffic and now offered a natural defensive position. When French’s division had marched away from Sedgwick, it had become engaged with troops from three brigades of Hill’s division, which had pulled back from the fighting around the Dunker Church. A spirited battle erupted on the left of the sunken road. The famed Irish Brigade assaulted the Confederates, many of whom were from North Carolina and Alabama in the sunken road around 10:30 am, suffering 540 dead and wounded before falling back. Still, the Union attacks continued. Exhausted, the Confederates began to falter when a pair of New York regiments managed to flank the sunken road and pour deadly fire down the length of the trench and a misunderstood order resulted in an entire rebel brigade abandoning its positions.

Confederate bodies were heaped two and three deep in the sunken road, which came to be known to history as ‘Bloody Lane.’ Once again, the Union army stood on the brink of a decisive victory. A patchwork defence slowed the Union tide, which had reached up to 600 yards beyond the sunken road. One more push with fresh troops from his angle reserve might win the day for McClellan, but the commander hesitated and then ordered his troops to hold their positions.

From morning until mid-afternoon, Union troops further south had been attempting to take the lower bridge across Antietam Creek. While some of his troops found places where the stream could easily be forded, the corps commander, General Ambrose Burnside, was determined to take the bridge that would eventually bear his name. It was defended by only 400 Confederate riflemen from Georgia and South Carolina. After four hours of fruitless attempts to capture the bridge, Federal troops from New York and Pennsylvania charged across and gained the west bank.

Throughout the morning, Lee had stripped his right of troops to support those hard pressed areas on his left and centre. Now, in spite of his slow progress, Burnside was in position to sweep the woefully inadequate Confederate defenders aside, capture Sharpsburg, and cut off the entire rebel army’s avenue of retreat. He waited, however, for two precious hours, consolidating his hold on the west side of the creek. When Burnside finally got moving around 3 pm, he made sluggish progress. An hour later, he was only half a mile from the town. At the precise moment when he was needed the most, A.P. Hill and his Light Division appeared in a cloud of dust, bowling down the road from Harpers Ferry. His footsore soldiers had covered the 17 miles to the scene of the fighting in seven hours and many had fallen out of the ranks due to exhaustion. The charge of the Light Division stopped Burnside’s advance cold, and he retired toward the creek. By 6 pm, the Battle of Antietam was over. Lee was too battered to take the offensive.

The casualties from America’s bloodiest day were appalling. The Army of the Potomac counted 12,410 dead, wounded or missing, while the Army of Northern Virginia had lost 10,700. Throughout the day on the 18th September, Lee stood his ground. McClellan declined to renew the fight and did not pursue the Confederate columns when they withdrew across the Potomac.

Battlefield Bodies

Why Was Antietam The Bloodiest Battle In American History?

Aftermath

In the wake of the Battle of Antietam, President Lincoln became convinced that the outcome was enough of a victory to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves in territory then in rebellion against the United States. The document transformed the war from an effort to save the Union to one of liberation and the perpetuation of freedom. European governments, which had abolished slavery themselves, were dissuaded from supporting the Confederate cause.