The Benefits of Psychopathy in Crime

Being 'good' and being 'successful' are often merged together as an inevitable and inseparable rule of human nature. In fiction, the hero always succeeds because they are moral, but in actuality, one doesn't have to be 'good' or moral to be a successful soldier, spy or CEO. This leads to the topic of criminality: are psychopaths better equipped for crime due to their predisposition for ruthlessness and lack of remorse? Perhaps such characteristics are beneficial for a criminal behaviour.

Aharoni ( as cited in Dutton, 2012) surveyed over 300 inmates in prisons across America and calculated their criminal competence by comparing the number of crimes they had committed with the number of non-convictions. So if an inmate had a higher number of crimes committed than convictions, they would be considered more competent than someone who has been convicted for all of their crimes. Interestingly, Ahroni found that levels of psychopathy predicted criminal competence, suggesting that psychopaths can be more successful criminals. However, this largely depends on their level of psychopathy, those with extremely high levels where just as unsuccessful as those with low levels, but the inmates with a moderate level were the most accomplished criminals. This leads us back to Ray's model of life success (see this article) which claims that too much or too little reduces functionality, but if an individual can reach the optimum level of psychopathy, they can be functional in life and potentially in crime.

The PCL-R is one of the most famous diagnostic tools for psychopathy, and as most research into psychopathic characteristics is conducted on criminals, it provides a valuable insight into traits beneficial for a criminal career. Superficial charm and pathological lying grants psychopaths the seemingly supernatural ability to charm their victims into submission, such as con-men who thrive on these abilities; and a lack of empathy removes the guilt associated with such exploitation. A proneness to boredom and impulsivity provide a possible explanation for psychopathic crime but such behaviours, along with irresponsibility, may be a great weakness.

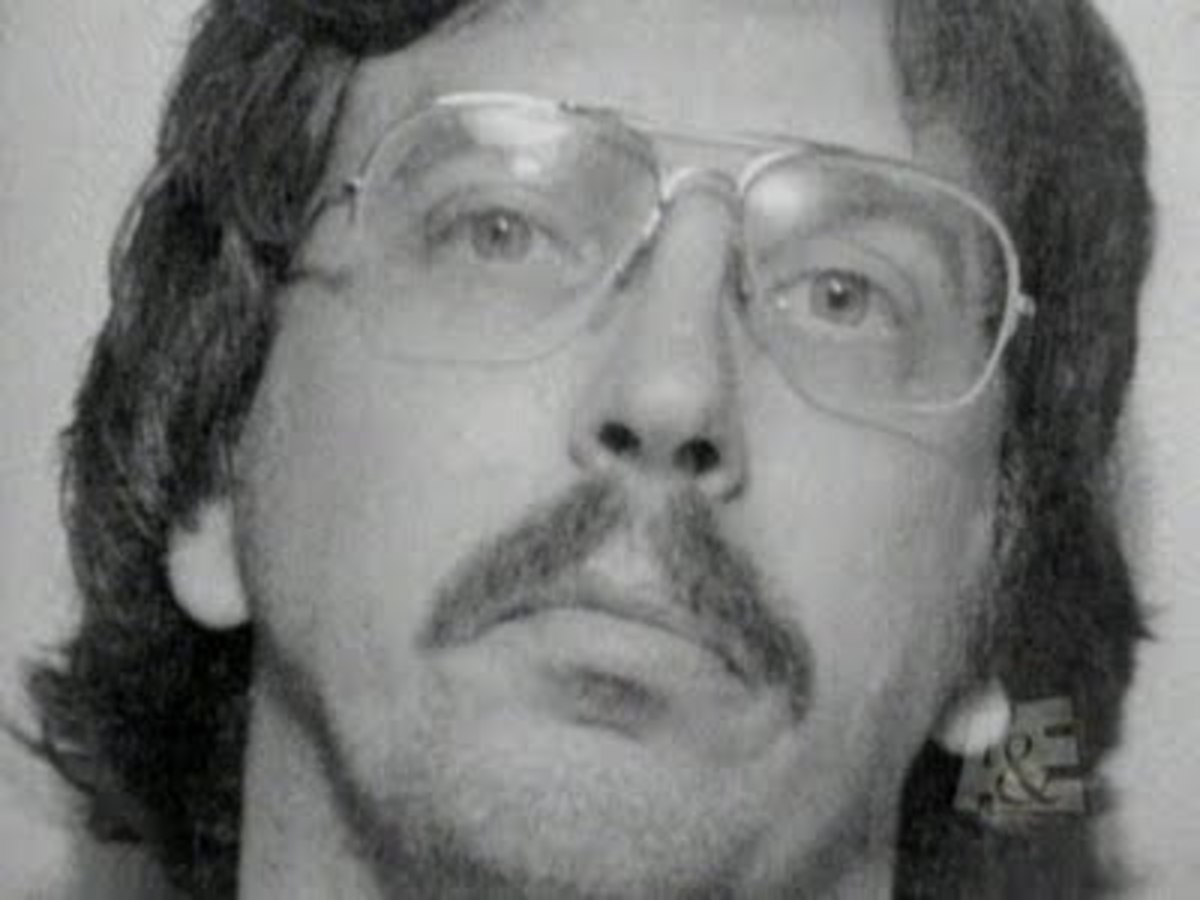

A famous example of these characteristics at play is the hitman Richard Leonard Kuklinski. He worked for the American mafia and performed many roles for the criminal organisation involving a large variety of crimes, from money laundering to contract killing and was nicknamed 'The Iceman'. Kuklinski's wife and children were unaware of his double life as a mafia hitman, suggesting he had brilliant skills of manipulation and superficial charm. He claims that he would kill anyone who would insult or try to testify against him, he was abusive to his wife and children and was also an avid gambler, suggesting impulsivity and proneness to boredom. After his lengthy criminal career, he began to become less pedantic when disposing of evidence (irresponsibility), which eventually brought about his imprisonment.

Dutton (2012) argues that a "con artist and secret agent are two sides of the same coin" so why is it that some turn to crime whilst others do not? Behaviourists may blame the likes of Kuklinski on parental figures, his parents were abusive and his father murdered Kuklinski's brother, perhaps his own violent behaviour can be boiled down to imitation of his main role models during childhood. However, the inheritance of violence may also be genetic; Christiansen (1977) studied monozygotic (mz - identical twins) and dizygotic (dz) twins and found evidence to suggest that criminality is partially genetic. Mz twins had an average concordance rate of 28% whereas dz twins had only 10.5%. The mz twins had a higher concordance rate suggesting that there is a genetic influence on criminality.

However, the concordance rates were still low which implies that biological explanations do not, with 100% certainty, determine an individual's likeliness to commit crime. The diathesis stress model proposes that behaviour is determined by a combination of the two; some are genetically predisposed for certain behaviours but environmental factors affect whether these genes are 'activated'. Needless to say, a combination of biological and environmental factors influence behaviour but what, specifically, makes a psychopath become a "con-man" or a "secret agent"?

According the the PCL-R, criminal versatility, juvenile delinquency and poor behavioural controls are all psychopathic behaviours, suggesting an innate predisposition for crime. Characteristics such as pathological lying, manipulativeness and a lack of empathy provide useful tools for a career in crime, yet can also be beneficial in a different context. All these traits can also be useful in corporations or in the military. If environmental factors such as upbringing can cause criminality, child protection policies could reduce juvenile delinquency. Our contemporary society is defined by increasing life quality and is marked by the introduction of such child protection laws, these laws can prevent youths from offending. Thus leading young psychopaths along a career path more beneficial to society.

Even if psychopathic traits can be beneficial for a career in crime, they are especially damaging to the victims of these crimes. Ronson (2011) claims that "psychopaths are to blame for this brutal, misshapen society" which is supported by Hare and Babiak (2006) who argue that "both male and female psychopaths commit a greater number and variety of crimes than do other criminals. Their crimes tend to be more violent... general behaviour more controlling, aggressive, threatening, and abusive". Subjectively, psychopathy is both useful and damaging which makes it difficult to quantify to what degree, if any, psychopathic traits are beneficial.

However, as Dutton and McNab (2014) argue, if psychopaths have the optimum level of psychopathy they can be functional. If for instance, an individual has low levels of impulsivity and high intelligence they could become a very successful surgeon, soldier or criminal mastermind.

Mcnab and Dutton (2014) claim that "you don't need to be a good psychopath to be successful". They suggest that success is not always something that is defined by society, but by individuals. They also propose that success or functionality of a psychopath is largely determined by a combination of their individual personality traits and the environment. They use the example of how intelligence and predisposition to violence can affect success and functionality in different fields of work (see figure 1).

Psychopathic

| High Inteliigence

| Low Intelligence

|

|---|---|---|

Violent

| Functional successful (eg. special forces, criminal mastermind)

| Dysfunctional unsuccessful (eg. low-level thug, enforcer)

|

Non-violent

| Functional successful (eg. lawyer, surgeon, CEO)

| Dysfunctional unsuccessful (eg. petty criminal)

|

Figure 1. Dutton and Mcnab (2014)

Psychopaths, just like everyone else, are neither 'good' nor 'bad', beneficial or damaging; instead, they are a combination of the two and the extent of their usefulness is largely determined by individual personality and behaviours. Certain psychopathic traits can be useful for individuals or organisations to achieve their goals yet other characteristics such as irresponsibility can be damaging. Psychopaths are portrayed as evil creatures that are not human due to their shallow emotions, but this stereotype is unfair. They can be beneficial, research suggests that they can even be more moral than the rest of us (see this article). Although psychopaths may differ from 'normal' people, in many ways, just like anyone else they are capable of becoming serial killers or war heroes, business leaders or ordinary human beings.

References

Babiak, P. , Hare, R. (2007). Snakes in suits: when psychopaths go to work. Published New York, Regan Books.

Christianson, K. O. (1977). A review of studies of criminality among twins. Mednich SA, Christianson KO: Biosocial Bases of Criminal Behavior. New York, Wiley.

Dutton, K.. (2012). The wisdom of psychopaths: lessons in life from Saints, spies and serial killers. Published London, William Heinemann.

Dutton, K. , McNab, A. (2014) The Good Psychopaths Guide to Success. Published online, available at https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/The to_Success.html?id=FEmG AwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp read button&redir esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=f

Ronson, J. (2011) The psychopath test: A journey through the madness industry. Published London: Picador.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2020 Angel Harper