- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

The Hays Guards: The Story of Company K of the Sixty Third Pennsylvania Volunteers (Part Four)

This is part four of a six-part series. To read part one, click here. To read part two, click here. To read part three, click here

Desertion in the army was a problem during the Civil War. Some statistics suggest that as many as 5000 men deserted from Union forces every month. Company K itself had six desertions. On 12 December 1863, the same day as the Battle of Fredericksburg, Privates Stewart Hodge and George Mulholland deserted. They had been with the regiment since mustering in in August of 1861. Three draftees also deserted in 1863 between September and November; Jacob Barnhart, Lemuel Kemp and Davenport Riley.

In the early days of September 1863, the regiment received orders to begin marching south. During this march south, the veterans had a good laugh at the expense of the draftees. A number of the new soldiers had insisted on packing everything they had brought for the march south and soon found their packs cumbersome. Eventually the draftees were discarding all but the bare necessities from their packs and were carrying the same items as the veterans.

The Sixty-Third forded the Rappahannock River once again on 16 September and made temporary camp a few miles from the town of Culpeper, Virginia. Since Culpeper was considered a hotbed of secession and its citizens hated anything to do with the Union, soldiers from the Army of the Potomac were ordered not to visit the town. Confederate guerillas roamed the woods in the area, making it unsafe for any soldier to venture from camp.

The regiment stayed near Culpeper for about a month. In October, General Lee’s army was spotted trying to cut off the rear of the Union’s army, which made it necessary for the regiment to retreat back across the Rappahannock. On 13 October, members of the regiment who were on picket encountered Confederate cavalry at Auburn Creek, Virginia and a skirmish broke out. Other skirmishes would take place over the next few days, but there were few casualties in the regiment. Company K's First Lieutenant Thomas W. Boggs was wounded and later discharged because of those wounds. The troops of the Third Corps received a boost to their morale on 15 October when General Daniel Sickles visited them in his new carriage. The troops of the Sixty-Third were then moved to Fairfax Station, Virginia. They continued their pickets and patrols in the surrounding area until the first week of November.

Early on the morning of 7 November, the regiment was given orders to move along the Orange and Alexandria Railroad and assist in the rebuilding of parts of the railroad that had been destroyed by fighting. The regiment was then sent to Kelly’s Ford, where they assisted Major General William French’s forces in battle with the Confederate troops. The Sixty-Third entered the Battle at Kelly's Ford briefly, but suffered a casualty when Captain Timothy Maynard of Company B was shot through the bowels as he offered water to a wounded rebel officer.

On 8 November the troops under Major General French’s command met up with the rest of the Army of the Potomac, which had taken Rappahannock Station five miles north of Kelly’s Station at Brandy Station, Virginia. Over a thousand Confederate soldiers were killed, wounded or captured, whereas the Union had casualties numbering just over 400. For a few weeks, the regiment remained on the farm of John Miner Botts, located just outside Brandy Station.

On 26 November, the Sixty-Third was part of a group of soldiers sent across the Rapidan River to assist the Third Division at Locust Grove, some woods near Jacob’s Ford. Major General French had made a stupendous blunder and had sent a division of his corps into a dense growth of trees blindly. The Union troops surprised a corps of Confederate soldiers as well as themselves, and in the skirmish that ensued, several men were lost in a lively fight.

Over the next few days, an icy rain fell and chilled the men. Because the enemy was extremely close and strongly entrenched at Mine Run, Virginia, Union soldiers were not allowed to kindle fires and many became sick. Some froze to death or lost limbs to frostbite. On top of that, they were sleep deprived because two mornings in a row, the 29th and 30th of November, the Army of the Potomac was roused at three in the morning and marched to the frontlines, expecting engagements that never came.

The reason these assaults were never made was because Major General Gouvernor Warren deemed that the Confederates were firmly entrenched and had been moving to counter any attack by Union Troops. General Warren decided it was better to risk being court-martialed for disobeying orders then to send the troops in his command to their deaths. The freezing weather and the dwindling supply of provisions were also factors in this decision.

On 1 December 1863, the Army of the Potomac retreated from Mine Run. In their wake, they left destruction as they burned houses and outbuildings and destroyed roads for amusement. Disheartened, the army stumbled into their old camps at Brandy Station on 3 December. The soldiers were weary, worn out and disheartened, but eager to rest in their comfortable camp for the winter. In January of 1864, a limited number of leaves of absences and furloughs were granted to the veterans of the Sixty-Third. Visits from Northern Ladies’ Aid Societies and high ranking officials helped to raise morale. Talent shows for the soldiers were organized, and entertainment was brought from as far away as New York City and Philadelphia.

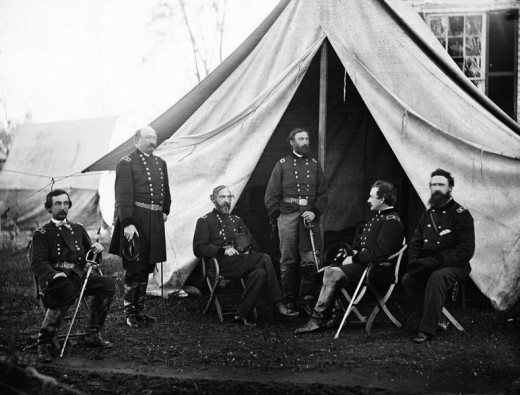

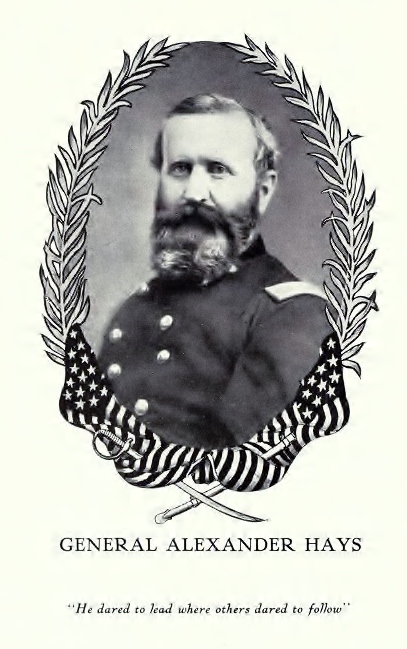

In March 1864, reorganization of the Army of the Potomac occurred and the decimated Third Army Corps was disbanded, much to the chagrin of the Sixty-Third Pennsylvania and the remains of other regiments that made up that particular hard-working corps. The soldiers of the former Third Corps were allowed to keep their red patches, but many voiced their displeasure at the heroic Third Corps being disbanded. A few showed their displeasure by setting up a small cemetery in the camp and erecting a tombstone dedicated to the Third Corps, which they felt had been “killed in action.” The Sixty-Third was reorganized into the Second Brigade of the Third Division of the Second Corps. The only joy that came of this reorganization was that they were once again under the command of General Alexander Hays.

The men moved into new quarters in camp after the reorganization. They were brought under review several times before leaving camp finally on 26 April 1864.

(Author’s note: One of the men of the PA 63rd, John D. Wood, was my great-great grandfather. I do not know what happened to any of the other men of the regiment nor do I have biographical information past what I have listed for some of the other men in this series of articles. If you have information you would like to share on any of the men listed in any part of “The Hays Guards: The Story of Company K of the Sixty Third Pennsylvania Volunteers” please do not hesitate to leave a comment or contact me via my family tree website. I do edit this series with genealogical information from others as I get it. I would also like to offer my most profound appreciation to my distant cousin and collaborator, William Bozic for his insights and edits to this series. I thank him immensely for the time and effort he has put in to making this work what it is.)

Recommended Reads

Works Referenced

63rd Pennsylvania Infantry. Civil War Index: Primary Source Material on the Soldiers and the Battles. 2010. Online at http://www.civilwarindex.com/armypa/63rd_pa_infantry.html

63rd Pennsylvania Regiment. Pennsylvania Civil War Volunteers. 2012. Online at http://www.pacivilwar.com/regiment/63rd.html.

Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War and of the Rebellion Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of Several States , the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources. The Dyer Publishing Company: Des Moines. 1908.

Civil War Battle Fields. Civil War Trust. 2011. Online at www.civilwar.org/battlefields

Hawks, Steve. 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. Civil War in the East. Hawks Interactive. 2012. Online at http://www.civilwarintheeast.com/USA/PA/PA063.php

Hays, Gilbert A. Under the Red Patch: The Story of the Sixty-Third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers: 1861-1865. Sixty-Third Pennsylvania Volunteers Regimental Association: Pittsburgh. 1908.

National Park Service. Battle of Mine Run. Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. Department of the Interior. 2012. Found online at http://www.nps.gov/frsp/mine.htm

National Park Service. Battle of Rappahannock Station. Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. Department of the Interior. 2012. Found online at http://www.nps.gov/frsp/rapp.htm

Tighe, Adrian. The Bristoe Campaign: General Lee's Last Strategic Offensive with the Army of Northern Virginia - October 1863. Xlibris: Bloomington. 2011.