- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

The Hays Guards: The Story of Company K of the Sixty Third Pennsylvania Volunteers (Part Three)

This is part three of a six part series. To read part one, click here. To read part two, click here.

The purpose of the Gettysburg campaign on the part of Confederate General Robert E. Lee was to draw fighting away from the ravaged fields of Virginia as well as play to the peace-loving Northerners. His hope was that if he could win a battle in the North, the Union would give up fighting and let the Confederacy be. He also was hoping to procure badly needed supplies for his troops from the farm fields of Pennsylvania. Lee was also interested in disrupting Union supplies and gaining support from European powers. Because of this, he traveled north with his army. His intent was on capturing Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, but they met upon Union troops outside of Gettysburg instead.

Union soldiers were waiting for him. For a time, the Pennsylvania Sixty Third, as part of the Third Corps of the Army of the Potomac, was engaged in watching the movement of the Confederate Army as Lee’s troops made their way to Gettysburg. They continued to march to the defense of the city, while keeping an eye on their enemy’s troops.

The men of the Sixty-Third did not see much combat the first day because they were ordered to be available for picket. They could hear the sounds of the cannons but did not see much of the action until the following day. They spent an uneasy night upon the picket line. There were a few fights during the night as Union and Confederate pickets spotted each there, but for the most part it was a quiet night.

The Sixty-Third was stationed to the left of the battlefield on 2 July 1863, just west of and behind the Joseph Sherfy House, which would see much fighting in the battle in the Peach Orchard section of the battlefield. After a morning of skirmishing with the enemy, the Confederate army opened fire with cannons. For two long hours, the regiment and much of the Third Corps under Corps Commander Major General Daniel Sickels was exposed to a terrible and constant fire of artillery from the southern troops. Then suddenly men came rushing towards them in an advance. Men were fighting in hand to hand combat, which became quite intense as the soldiers defended their state’s land. Eventually the regiment was ordered to fall back and yield the field. This was at five in the afternoon, after having been engaged in the battle since nine in the morning. That night, they were ordered to the picket line and posted near Little Round Top, to the south of Gettysburg

The next day, the Third Corps was posted between Little Round Top and the Peach Orchard, where they witnessed Pickett’s desperate charge. From here, they were ordered to move double quick to protect the Union artillery from the Confederate charge. However, as soon as they came into position, they heard cheering as the Confederate troops retreated. The battle was over. The day was 3 July 1863.

Feeling inspired, General Hays grabbed up three of the Confederate flags that his men had captured and offered one each to his two aides, a Captain Cotts and a Lieutenant Shields. The three men mounted their horses and triumphantly rode to the line with the flags, which they had allowed to drag in the dirt. They let out a cheer at the still retreating Confederate army before returning with the flags, handing them back to their Union captors. Out of the 33 Confederate flags that were captured by Union soldiers, the men under Hays’ command had taken 22. Seven of those were never turned in to the Army, as they had been secreted away by men who wanted them as souvenirs.

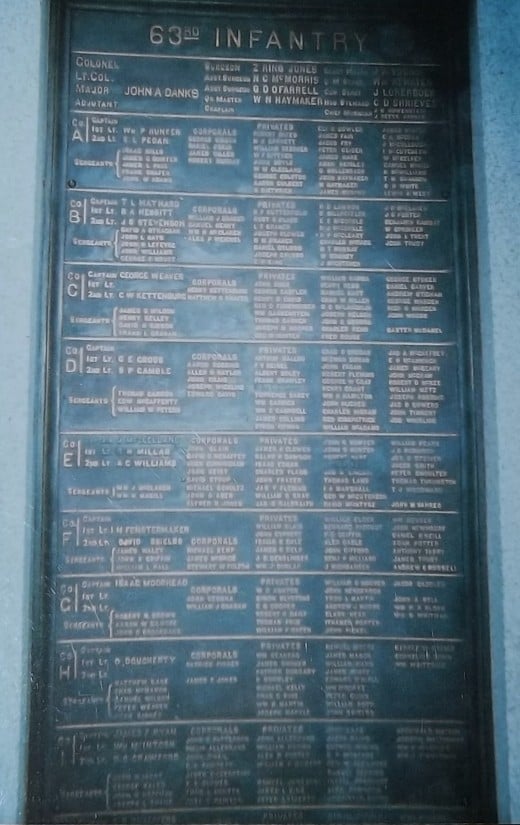

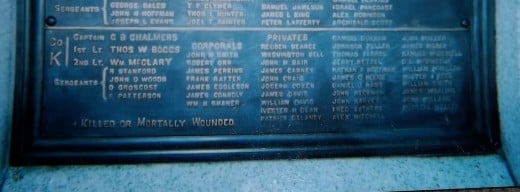

Though battle-weary after three days of fighting, the troops of the Sixty-Third remained on the battlefield to bury the dead as well as tend to the wounded soldiers.One man from the Pennsylvania Sixty-Third was killed outright; Corporal David Stoup from Company E. 29 others were wounded, some mortally, and 4 were found to be captured or missing, though only one of Company K was injured, Private Walter Reed. In their retreat, the Southern army had abandoned some of their dead and their wounded, and the Union took it upon itself to take care of those casualties.

The Sixty-Third also assisted in overseeing the retreat of Lee’s men, a feat that took several days. Some wanted to go after the tattered Confederate army, including President Lincoln, but General George Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, decided it was best not to attack the retreating army but to take care of the wounded men that were left as a result of the battle. Some sources speculate that had Meade gone after Lee immediately after this battle, the war would probably have ended then, as Lee’s troops were too weak to continue fighting. However, Meade allowed the enemy to escape back into Virginia via the Appalachian mountains, making the war drag on for two more years. Other sources concur with newly appointed commander of the Union Army of the Potomac General George Gordon Meade's astute decision not to risk his exhausted army in a hasty fight with the Army of Northern Virginia.

During the retreat of the Confederates from Gettysburg the Sixty-Third received news of General Ulysses S. Grant’s victory over the Confederates at Vicksburg. There was much rejoicing, as Gettysburg and Vicksburg were two substantial wins for the Union cause.

The Sixty-Third stayed at Gettysburg until the 14th of June, by which time Lee's army had crossed the Potomac back into Virginia. The regiment then moved south, for now the Army of the Potomac had decided to act. By 23 July 1863 the regiment had made its way to Warren County, Virginia. Here, Union forces tried to push back the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia through the Blue Ridge Mountains at Wapping Heights, also know as Manassas Gap. This battle was small compared to previous battles the men had seen and there were relatively few causalities. After the battle the Union army retreated back to their familiar camp grounds six miles from Warrenton, Virginia. Here the men were assigned to picket duties once more.

Late July through August 1863 the regiment received 300 new soldiers, all of whom were draftees. There was a bit of uneasiness amongst the soldiers, as the veterans had heard stories about draft-dodgers and those who had been paid to take the place of those drafted. The veterans also felt that these draftees were beneath them, as they waited to be drafted rather than enlist. The new conscripts, as the veterans called them, were considered dodgy, and one story states that one even had made a walking speakeasy by which the draftees could buy booze.

It was while they were stationed on this duty on the line of the Rappahannock River that the veterans each donated a day's pay to buy a carriage for General Sickles. He had lost his leg when a cannon shattered it during the Battle of Gettysburg and then men thought so highly of him that they wanted to pay a tribute to him.

The Sixty-Third remained in camp and did not see action until October, when they participated in the Bristoe Campaign.

(Author’s note: One of the men of the PA 63rd, John D. Wood, was my great-great grandfather. I do not know what happened to most of the other men of the regiment nor do I have biographical information past what I have listed for some of the other men in this series of articles. If you have information you would like to share on any of the men listed in any part of “The Hays Guards: The Story of Company K of the Sixty Third Pennsylvania Volunteers” please do not hesitate to leave a comment or contact me via my family tree website. I do edit this series with genealogical information from others as I get it. I would also like to offer my most profound appreciation to my distant cousin and collaborator, William Bozic for his insights and edits to this series. I thank him immensely for the time and effort he has put in to making this work what it is.)

Recommended Reads

Works Referenced

63rd Pennsylvania Infantry. Civil War Index: Primary Source Material on the Soldiers and the Battles. 2010. Online at http://www.civilwarindex.com/armypa/63rd_pa_infantry.html

63rd Pennsylvania Regiment. Pennsylvania Civil War Volunteers. 2012. Online at http://www.pacivilwar.com/regiment/63rd.html.

Battle of Gettsyburg: Day 2. Military History Online. 2012. Online at http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/gettysburg/getty24.aspx

Bozic, William. Civil War Battlefield Tour - A Photographic History into the Regiments of John Denver and William W. Wood. 2005. Online at http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~kelleywood/westpennsylvania/Civil%20War%20Tour/civilwarbattlefieldtour.html

Brann, James R. Defense of Little Round Top. Civil War Trust reused with permission from History.net. 1999. Found online at http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/gettysburg/gettysburg-history-articles/defense-of-little-round-top.html

Davis, Kenneth C. Don't Know Much About History: Everything You Need to Know About American History But Never Learned. Perennial: New York, 2003.

Donald, David. Divided We Fought: 1861-1865. The MacMillian Company: New York. 1952.

Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War and of the Rebellion Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of Several States , the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources. The Dyer Publishing Company: Des Moines. 1908.

Civil War Battle Fields. Civil War Trust. 2011. Online at www.civilwar.org/battlefields

Hawks, Steve. 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. Civil War in the East. Hawks Interactive. 2012. Online at http://www.civilwarintheeast.com/USA/PA/PA063.php

Hays, Gilbert A. Under the Red Patch: The Story of the Sixty-Third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers: 1861-1865. Sixty-Third Pennsylvania Volunteers Regimental Association: Pittsburgh. 1908.

Tindall, George Brown and David Emory Shi. America: A Narrative History. Volume 1. 5th Ed. W. W. Norton and Company. New York. 2000.

Shotgun's Home of the American Civil War. 2003. Online at http://www.civilwarhome.com/