- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

The Lessons of the Japanese Interment for Today

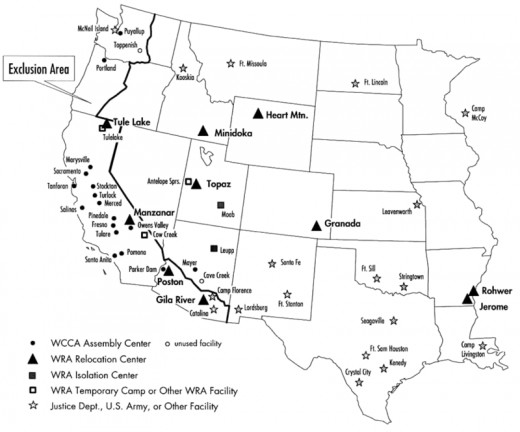

During the Second World War, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, some 110,000 Japanese-Americans were interned on the US West Coast, after being forcibly removed from their homes. They would be kept in camps for years, until 1944 - or even into 1945 - with the exception of those who were released for agricultural labor or to join military units, ironically defending a country and the liberties which were denied to them. After the war, they still faced discrimination. Future US senator Daniel Inouye, stopping in San Francisco after losing an arm from fighting in Italy and with a chest bedecked with ribbons and medals upon his U.S army uniform, was denied service with the words "We don't serve Japs here", from a barber. His tale was just one of many. Although some amends would later be made with cash grants from the US government, the wounds caused by the war were still deep/

To a certain extent, the internment of the Japanese Americans during WW2 is no longer controversial, so unanimous is its condemnation. Personally, I have never heard of any serious contemporary intellectual defense being mounted in defense of the policy undertaken by the US government towards its Japanese American citizens during the Second World War. The only citation of such an attempt was to claim that in doing so the US was protecting the security of the Japanese Americans from possible violence, a weak defense at best, and one which could easily have been solved in measures that did not themselves cause so much harm. I believe that today the argument put forth in such a situation would nearly unanimously be the same as with any other Americans - - to watch suspicious individuals as national security necessitates, and to respect the civil rights of US citizens, instead of preventively detaining an entire group for no greater purpose than that they were Japanese. Hence, to mount any defense of the US government seems foolish, and instead the question should aim to answer: what went wrong, and why?

To start first, of course the event was motivated by wartime paranoia and long-standing ethnic prejudice from other Americans towards the Japanese immigrants. Such prejudice against other ethnic groups, always a common theme in American history, was thus naturally easy to exploit come wartime. Divided from American society by exclusionary limitations which prevented many Japanese from assimilating, Japanese were then accused of being incapable of being assimilated and then imprisoned, a vicious paradox. The same did not happen to Americans descended from Germans or Italians, despite these two nations being also part of the war against the United States. This prejudice must stand first in any depiction of the misfortune which befell the Japanese-Americans, and despite our hopes for a more tolerant and changed America, is doubtless something which rests with us until today.

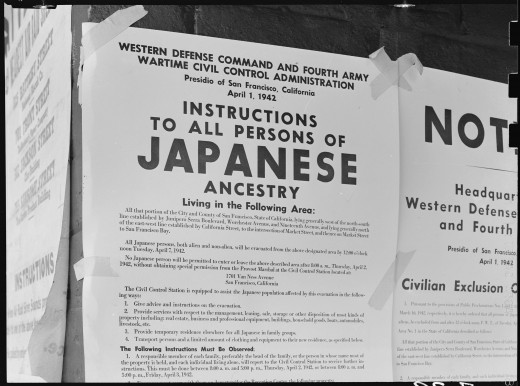

As easy as it is to see these problems of ethnic prejudice and wartime paranoia, the incident of the Japanese Americans also demonstrates a terrible tendency of humanity to enjoy downplaying and mischaracterizing events to improve our own guilty conscience - - indeed, the preceding line in this paper might demonstrate exactly such a phenomenon, avoiding the usage of the word “tragedy” or a word of similar ilk to prefer the dry, colorless, and thoroughly neutral “incident”. Americans so too, in addition to never referencing the Japanese precisely, would go so far as to deceive themselves - - or at least to tell a breathtaking twisting of the truth - - that the Japanese Americans were “refugees”, who they were generous in taking care of. American language constantly changed in such a way to attempt to comfort themselves. Thus by the time of the Presidential proclamation upon the matter, “excluded enemy aliens,” became “evacuated people,” and internment camps stopped being viewed as such and instead as “community centers” and “wartime homes.” Americans seemed well capable of exercising dismal doublethink concerning the deportees, at once writing about their apparent patriotism in saluting the American flag just days before Pearl Harbor with the “Pledge of Allegiance” photo by Dorothea Lange, and yet seeming to not find any disjuncture between this and their deportation, done supposedly for national security reasons.

Perhaps the most dismal of all are the economic causes which led to Japanese-Americans undergoing such a fate. With up to $200,000,000 of property left behind, and the need often to sell it at firesale prices, obvious opportunities for usury existed. At the same time, in Hawaii, where Japanese made up 35% of the population, they were not interned : in America it was profitable to intern them to steal their property, while they were too vital as part of the labor force in Hawaii. Some restitution was made post-war, but still much was lost. Unfortunately, this economic incentive is something which will always exist in the oppression of a minority group.

The only hope which can be marshalled from the experience of the Japanese Americans in the Second World War is that they will serve as a warning clarion towards the future, concerning the dangers of popular opinion, ethnic divisions, wartime paranoia, and mealy-mouthed language which seeks to obscure our crimes and to turn reality upon its head. Unfortunately, the drivers and motivations which saw them stripped unjustly of their civil rights will always remain at the heart of the soul of man, and the institutions which exist to guard our rights and liberties have always been as fallible as ourselves.

© 2017 Ryan Thomas