- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

The Spanish Civil War

Background

In the 1920s and 30s Spain was prey to chronic political instability and social unrest that would pave the way towards a brutal and bloody civil war. At the beginning of the twenties Berbers in the Rif region of Spanish Morocco rebelled against colonial rule. Led by And el-Krim, they inflicted a severe defeat on the Spanish at Annual in 1921. Partly in response to setbacks in Morocco, in 1923 General Miguel Primo de Rivera formed a government under King Alfonso XIII. Over the following two years, Spanish and French forces crushed the Rif revolt. The Spanish Army of Africa, which consisted of Spanish Foreign Legion and Moroccan troops, emerged as a battle hardened force under officers such as General Francisco Franco.

In 1930/31 mounting unrest in Spain led first to the deposition of Primo de Rivera and then the overthrow of the monarchy. However, the democratic republic born of this peaceful revolution degenerated into a fierce political battleground, with fascist, anarchist, socialist and monarchist movements all in contention. In 1934 a full scale workers’ revolt in the northern province of Asturias was crushed by the army.

Two years later a general election saw a Popular Front government sweep into power, the government was essentially a coalition of liberal and left wing parties. Over the next few months there were many outbreaks of violent disorder perpetrated by both left and right wing groups.

The Theatre Of War

Franco

Advance From Africa

On the 17th July 1936 the Spanish Army of Africa launched a rebellion to overthrow the Popular Front government. At first though, it seemed like this rebellion was doomed to end in failure. Its most experienced forces were Foreign Legionnaires and Moroccans. The main reason why this rebellion seemed destined to fail was the fact that the navy was stoutly loyal to the government, meaning of course that the troops could not cross over to the mainland.

The head of the African forces, General Francisco Franco requested assistance from both fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. The arrival of German transport planes at the end of July allowed Franco to fly 15,000 troops across to Seville in just 10 days; it was also the first airlift in history. With air cover provided by Italian bombers, other troops were ferried by boat across the straits. The Army of Africa marched north to Badajoz and west to Toledo, massacring thousands of militiamen and suspected loyalist sympathisers in the process. At Toledo on the 28th September the Army relieved a Nationalist garrison in the Alcazar fortress, which had been under siege for 10 weeks.

The Popular Front

The Nationalists

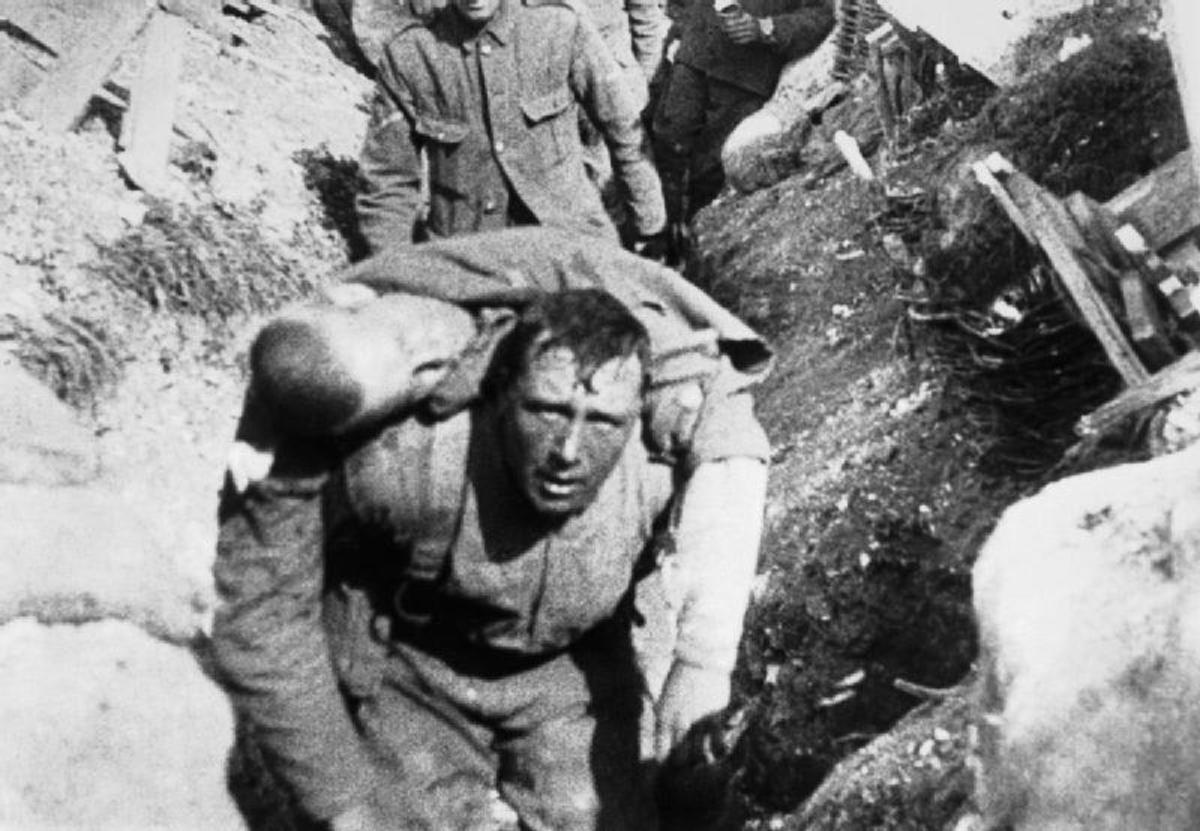

Characterising The War

The division of Spain between the Popular Front’s Loyalist Republicans and Nationalist rebels was complex, both politically and geographically. The Republicans included Basque and Catalan separatists, and every shade of left wing group from moderate socialists to communists, anarchists, and Trotskyists, all often bitterly hostile to one another. The Nationalist side ranged from Catholic conservatives to fascists and monarchists, but was held together by the dominant personality of Franco, who had gradually imposed himself as undisputed leader. Right from the outset, the war was marked by massacres and atrocities carried out by both sides. Although the killings made by the Nationalists were more systematic and claimed a far heavier toll in lives. Despite Republican forces being made up primarily of irregular militias, there was little guerrilla warfare. The style of combat was conventional and often static in the manner of World War I, with entrenched infantry confronting one another for long periods on immobile fronts. The ‘modern’ element in the fighting (aircraft and tanks) came mostly from foreign forces, some 50,000 Italians and 12,000 Germans, as well as contingents from Portugal, were sent to fight for the Nationalists. A much smaller number of military personnel sent by the Soviet Union made a vital contribution to the Republican cause, organising air and armoured forces. Some 40,000 foreign volunteers fought for the Republic in the International Brigades, organised by the communists. Britain, France and the US followed a policy of non-intervention, imposing an arms embargo that, in practice, favoured the Nationalists.

Madrid Under Attack

Defence Of Madrid

By October 1936, it seemed like the war was drawing to a swift end as Nationalist forces advanced rapidly towards Madrid from two directions. From the south came the Army of Africa, with another army led by General Emilio Mola advancing from the north. The first arrival of Soviet military supplies was followed on the 8th November by the first detachment of International Brigade troops.

By this time, the Nationalists were already in the Madrid suburbs; their presence forced the government to flee to Valencia, leaving General Jose Miaja in command. Madrid soon came under heavy artillery and aerial bombardment, but remarkably the city’s defences held out. One International Brigade, the 11th, a seemingly bedraggled collection of makeshift militias, which included anarchists, communists and women’s brigades, fought the Army of Africa to a complete standstill. Madrid remained under siege though, for the duration of the war.

On The Offensive

Preparing To Fire

Guernica

A Writer At War

Guadalajara And Guernica

In February 1937 the International Brigade held Franco’s Nationalists in desperate fighting in the Jarama valley, east of Madrid. Italian general Mario Roatta decided to attack towards Guadalajara, intending to join up with Franco’s forces. The initial advance on the 8th March, spearheaded by over 100 light tanks supported by artillery, broke through the thinly held Loyalist line, but the Italians were hampered by snow and sleet, for which they were ill prepared. Franco remained passive though, allowing the Loyalists to transfer forces from the Jarama front. These included the Garibaldi Battalion, largely composed of anti-fascist Italians, who found themselves fighting an Italian civil war on Spanish soil. Four days later, on the 12th, the Loyalists mounted a counterattack, deploying newly arrived Soviet tanks that outgunned the Italian armour. At the same time Loyalist aircraft carried out ground attack missions to devastating effect, and the Italians were driven back in disarray. Guadalajara was a small defensive victory for the Loyalists and thus gave them a timely boost in morale and also severely dented the prestige of fascist Italy.

In spring 1937 the Nationalists sought to push into the northern regions of Spain, namely the Basque area, who supported the Republic because it offered them regional self- government. General Mola launched a campaign against the Basque country, threatening to raze it to the ground ‘if submission was not immediate.’ The Basques put up a brave fight, but in late April they were falling back towards Guernica, a market town of symbolic importance as the ‘cradle of Basque culture.’ The German Condor Legion under Wilhelm von Richthofen was carrying out air attacks in support of the Nationalist offensive- officially attacking military targets, but expressly ‘without regard for the civilian population.’

On the afternoon of the 26th April the Condor Legion struck at Guernica. They might have been delivering a blow against Basque morale, or they might have been seeking to destroy a bridge to block the withdraw of Basque forces. Either way, the effect was devastation. The German bombers went in first, followed by transport planes that had been roughly adapted for bombing missions. In wave after wave of ‘shuttle’ attacks, dropping a mix of incendiaries and 550Ib bombs, they destroyed two thirds of Guernica’s buildings. Basque spokesman Father Alberto Onaindaia, who arrived at Guernica at the same time as the aircraft, described seeing German fighters actually strafing civilians. ‘The planes descended very low, the machine gun fire tearing up the woods and roads, in whose gutters, huddled together, lay old men, women and children.’ Hundreds of civilians were killed; the bridge said to be the primary target of the raid was not hit. Reports from foreign journalists who witnessed the aftermath ensured that Guernica would synonymous with the ruthless bombing of a civilian population.

The Americans Who Went To Fight In Spain

Nearing Victory

More On The Spanish Civil War

The Latter Stages

By the winter of 1937 the Nationalists had overrun the Basque country and were preparing a decisive offensive against Madrid. To forestall this attack, General Vicente Rojo launched an offensive against the Nationalist held city of Teruel. The attack achieved complete surprise, trapping a Nationalist garrison inside the city. Franco responded as the Loyalists had hoped by transferring forces to the Aragon front. The fighting took place on bleak, rocky terrain during one of the coldest winters on record. Many soldiers on both sides froze to death. On the 8th January, after house to house fighting, Teruel fell to the Loyalists, but they were themselves threatened with encirclement as the major Nationalist forces began to arrive. Amid recriminations between rival political factions, the Loyalists achieved a fighting withdraw under aerial and artillery bombardment, once more worsened by the Nationalists growing material and numerical superiority.

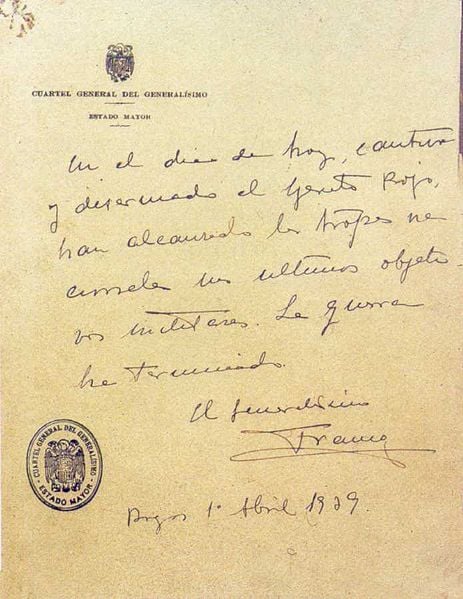

In summer 1938, facing almost certain defeat, the Loyalists launched a major offensive across the Ebro River, hoping that, if they demonstrated their ability to fight, the western democracies might yet come to their aid. Under General Juan Modesto, troops crossed the river by boat on the night of the 23rd and 24th July, the rest of the force crossing on pontoon bridges the following day. By the 1st August they had advanced 25 miles, but the Nationalists held a strong position at Gandesa. Both sides suffered heavy casualties in frontal assaults on entrenched positions. Nationalist artillery and air strikes by German Stuka dive bombers wore down the Popular Army, the remnants of which were driven back to their start point by mid-November. A Nationalist victory in the war was now a formality; which was officially completed by the 1st April 1939.

The Official End Of The War

Evacuation

More On Franco's Relationship With Hitler

- World War II: Hitler and Spain

This is a hub I wrote exploring the relationship between Hitler and Franco' Spain. I also look into how much Spain really participated in World War II.

Aftermath

The defeat of the Republicans allowed General Franco to install a right wing dictatorship in Spain that ended only after his death in 1975.

For the Republicans of course, defeat was a catastrophe. Some 50,000 Republican soldiers were executed, while many more were held prisoner for years and used as slave labour. A few escaped capture and maintained a low level guerrilla campaign into the 1950s. About half a million Republicans fled across the border into France when the war ended. Many thousands were still being held in French internment camps when France fell to the Germans in 1940. Consequently, many were handed over to the Nazis and met a tragic end in concentration camps.

Despite support from Germany and Italy in the Civil War, Franco kept Spain neutral during World War II. He entered negotiations with the Nazis, meeting Hitler at Hendaye in October 1940, but the two sides failed to agree terms for Spain’s entry into the war. Germany nonetheless reaped invaluable experience from the war in Spain, which allowed its armed forces to practise close air support, the operation of tanks in coordination with aircraft, and tactical bombing.