The Relationship between Transportation System and FDI into ASEAN Countries

Introduction

As various researches including Aitken and Harrison (1999) and Tsai (1994) have shown that foreign direct investment (FDI) has contributed significantly to economic growth, more and more economists and policy makers have paid closer attention to the determinants of FDI inflows into a country in order to find a way to attract more high-quality FDI projects to their countries. As for countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), FDI has become an important source of capitals, technology transfer, know-how transfer, access to foreign markets and stronger international economic cooperation. Over the past decade, although there was a considerable fluctuation in FDI inflows, generally, an upward trend can be seen across ASEAN nations. According to the World Investment Report 2014 compiled by the

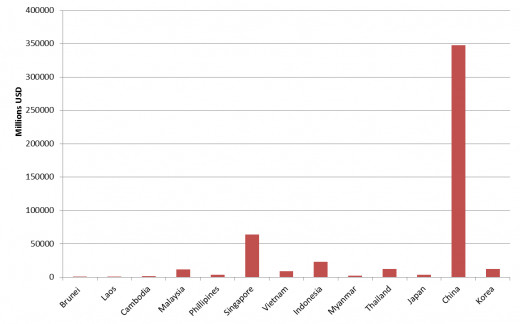

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), FDI inflows to ASEAN countries rose by 7% to reach USD 125 billion. Singapore, the regional economic giant, has consistently remained the most attractive FDI destination in Southeast Asia, accounting for more than half of the FDI inflows into the region. After ASEAN countries entered into the Regional Comprehensive Partnership (RCEP) with six countries, including Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand, FDI from these countries make up more than 40 per cent of FDI into the region.

In the past, research on the determinants of FDI inflows has concentrated chiefly on conventional factors such as macroeconomic variables, political environment, labor, natural resources and the ease of doing business, and there exist only a limited number of researches exploring the role of transport infrastructure in FDI attraction. However, with the advance of the globalization process, the importance of transport infrastructure has been underscored as transport infrastructure connects countries around the world and facilitates the movement of humans and goods. Such research as Wheeler and Mody (1992) claims that transport infrastructure also stimulates FDI inflows into a country by reducing the cost of doing business, saving time spent on transporting goods and products, improving a location’s accessibility and thus enhancing the company’s competitiveness. As a result, countries with reliable transport infrastructure such as modern road systems, international airports, and commercial water port and so on are believed to have a competitive advantage in attracting FDI. Moreover, Seetanah and Khadaroo (2007) also found evidence that the inflow of FDI capitals also simultaneously fostered the development of a country’s transport infrastructure to meet the demand of foreign investors.

Within this context, this research aims to determine the relationship between an improved transportation infrastructure system and the FDI inflow into a country, and whether this relationship is simultaneous. The author employed a cross-countries panel dataset covering ASEAN Plus Three countries (10 ASEAN countries plus China, Japan and South Korea) over the period of 2004-2013. This study is expected to contribute its empirical results for ASEAN Plus Three countries along with existing economic literature.

Literature review

Determinants of FDI inflows and transport infrastructure quality

Numerous researches have tried to figure out the determinants of FDI inflows into a country. Dunning remains one of the most influential authors on FDI literature. Based on the investors’ investment intention, he defines three types of FDI. The first type is market-seeking FDI companies, which want to find a new market and their products will serve the local needs. For this type of companies, characteristics of the local markets such as local taxation, demographic, market size and market potentials are very important. The second type of FDI refers to resource-seeking FDI companies. These companies invest abroad to take advantage of the resources not immediately available at their home countries, for example, low-cost labor, natural resources, raw materials or lax environmental regulations. The third type of FDI is efficiency-seeking FDI companies which move their operation in foreign countries to improve the efficiency of doing business. From this analysis, Dunning also groups determinants of FDI inflows into a country into three broad groups, namely ownership specific advantage, location-specific advantage and global advantages (Dunning, 1993).

According to a research by Ergogan and Unver (2015), determinants of FDI inflows can be classified into main categories relating to financial, demographic, economic, political and social factors. Utilizing a dynamic panel dataset encompassing 88 countries from 1985 to 2011, he finds out that variables such as the rate of urbanization, social security spending, per capita GDP, market size and corruption have statistically significant impacts on FDI inflow into a country. His study employs both static and dynamic methods, and the dependent variable is represented by three different measures which are percentage of FDI in GDP, FDI value added and transferred FDI from one country to another. Interestingly, this research also establishes that previous FDI levels also have significant impact on a country’s current FDI level (Erdogan and Unver).

In the article “Determinants of FDI in BRICS Countries: A panel analysis”, Vijayakumar, Sridharan and Rao examine the drivers of FDI flows to Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, five fast-growing emerging economies, using annual dataset spanning a 33-year period, from 1975 to 2007. They aim to use panel data analysis with three different techniques – common constant, fixed effects, random effects – to eliminate the problem of endogeneity within the model investigate. Their controlled independent variables consist of GDP, industrial production, workers’ wages, trade openness, exchange rate and infrastructure index. They find out that market size and infrastructure positively and significantly influence FDI inflows while labor cost and inflation rate negatively impact FDI inflows, leading to the suggestion that policy makers should focus on enhancing the investment climate to attract higher FDI level into their localities (Vijayakumar, Sridharan and Rao).

Dedicating specifically to uncover factors affecting FDI inflows into ASEAN countries and characteristics contributing to an attractive investment destination for United States’ firms, Uttama explores distinguishing features of ASEAN countries and important economic events occurring in the region such as the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the establishment of a free trade area, the passing of ASEAN Investment Area agreement, and so on. He also uses a panel country-level dataset and the gravity model to test two hypotheses that whether countries with similar size and relative factor endowments, high trade costs and low investment costs, bringing in more horizontal FDI and whether countries with different relative factor endowments, and low trade costs and investment costs bringing in more vertical FDI. He concludes that GDP level, trade cost back to the home country, distance between home and host country positively and significantly affect FDI into ASEAN, whereas skill difference, investment cost, and trade cost to host country negatively influence FDI (Uttama).

Relationship between FDI and transport infrastructure

On the relationship between FDI and transport infrastructure, in recent years, researchers have paid more attention to the role of transport infrastructure and separated its influence on FDI from that of infrastructure in a more general sense. In the article “Transport Infrastructure and FDI: Lessons from Sub Saharan African Economies”, Seetanah and Khadaroo assess how transport infrastructure adds to the relative attractiveness of a nation and how incoming FDI also helps to improve a country’s current transportation system. His research focuses on 30 countries in the Sub–Saharan African nations from 1984 – 2002. He argues that since transport infrastructure is essentially public goods provided by the government, the “free-riding” effect allows foreign investors to effectively share this resource without hurting the existing users. He develops a model with FDI as the dependent variable and natural resource intensity, market size, labor cost, human capital, political instability, openness and transport infrastructure as explanatory variables and uses dynamic panel data regression approach. He concludes that along with natural resources, market size, trade openness communication infrastructure, transport infrastructure clearly boosts FDI inflow, while the positive and significant lagged value of the dependent variable implies that FDI also confirms the presence of dynamism and endogeneity in FDI modeling (Seetanah and Khadaroo).

Applying a similar approach, Lichao explores the contribution of transport infrastructure in attracting FDI in East China, West China, and Middle China using fixed effect panel data method to evaluate data from 28 provinces from 1995 to 2008. He establishes that transportation system improvement plays an important role in driving FDI to a region, with the West and Middle Region witnessing a greater impact than the East Region. Moreover, the existence of transport infrastructure spillover effect indicates that the development of transport infrastructure in one province also benefits its neighbors (Lichao).

Methodology

As described above, there has been limited empirical work dedicated to studying the relationship between transport infrastructure and FDI inflows in ASEAN plus three countries, and most models ignore the feedback effect from the FDI inflows to transport infrastructure improvement. The presence of a reliable transport system makes a location appear more lucrative to foreign investors by lowering transportation costs, reducing wear and tear of company’s vehicles, ensuring the safety of goods during transportation and saving time for the company. On the other hand, the incoming FDI capital might improve the condition of transportation system in a country by providing incentives for local government to improve the location’s transport infrastructure, bringing in the necessary capitals, technologies and even consultancy. In addition, some foreign investors might even directly take part in big infrastructure projects by cooperating with the local government through public-private partnership or other type of partnership. Some local governments also negotiated with foreign investors to grant them investment only when the investors also help to improve the local infrastructure. Hence, the simultaneous relationship between FDI and transport infrastructure is worth considering.

In this paper, the author builds a model reflecting this relationship. Independent variables which go into each equation are chosen based on the previous literature review research. In order to capture the simultaneous relationships between FDI and transportation, a set of two simultaneous equations is specified as followed:

FDIi = β0+β1Trans + β2Res + β3Size + β4Trade + β5Education+β6Corruption + β7X + εi

(Seetanah and Khadaroo, 2007)

Where:

- FDI: FDI inflow to a country

- Trans: Transportation quality

- Res: Natural resource rent as a percent of GDP

- Size: Market size

- Trade: Trade openness

Since the simultaneous equation model suffers from simultaneity bias and cannot be easily estimated, a two-staged least squares technique will be employed instead. Two-staged least square is a modification of the ordinary least square technique, using two regressions for estimation. In the first stage, instrumental variables are used to obtain ordinary least squares predictions. In the following stage, the predicted values of the first regression will be utilized to generate the coefficients of variables of interest var.

In the equation, FDI denotes FDI inflows into a nation compiled by World Bank. Trans refers to the transport infrastructure in a country, quantified by the total length of road in a country. This data is collected by AJTP Information Center, and various research such as Lichao (2011), Seetanah and Khadaroo (2007) to esimate the quality of transport infrastructure. Res refers to the level of natural resources endowed for a country, estimating using the total natural resources rents as a percentage of GDP. Size means the market size of a location, representing by its GDP per capita. Trade embodies the openness of an economy, measuring by the proportion of trade in a country’s total GDP. Education measures the quality of labor and is quantified using the secondary school enrollment. Based on the previous literature review and others such as Scaperlanda and Mauer (1969), Zheng (2009), these variables are expected to have positive impact on FDI inflow. Corruption variable is also included to investigate what kind of impact corruption has on FDI inflow in ASEAN Plus Three countries. X encompasses a list of controlled explanatory variables including population, corporate tax, area and other type of infrastructure, specifically communication infrastructure (measuring by the number of Internet users in a country). The sign of the remaining independent variables are open to empirical findings. β0 is the constant and εi is the error term.

One difficulty facing with a cross-sectional statistical analysis is the presence of unobserved heterogeneity characteristics among nations. There are other unique features about each country that influences its FDI inflows and transport system and we do not have control over, nor could we ever observe all of them. Omitted variable bias will make the OLS estimate no longer consistent. The adoption of a two-staged least square allows us to eliminate omitted variable bias, assuming those variables are uncorrelated to the other independent variables in the equation.

FDI inflows into ASEAN +3 countries in 2013

Results

Data description

The main source for the data used in this analysis comes from the World Economic Indicator compiled by World Bank. The statistics for transport infrastructure for ASEAN, China, Japan, and South Korea are provided by AJTP Information Center. Corruption index is developed by Transparency International, an organization committing to combat corruption around the world. Due to the limited availability for data for the countries in the region, the dataset only spans over the period of 10 years, from 2004 to 2013; hence there are 130 valid observations for analysis.

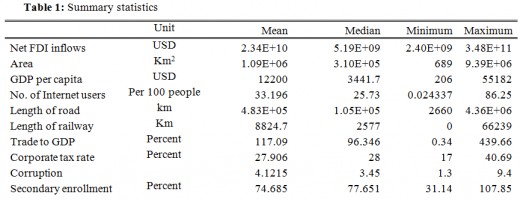

Table 1 summarizes the summary statistics of all variables. It is worth noticing that Singapore appeared to be the most attractive destination for FDI among ASEAN nations, but the total length of roads in Singapore is quite modest due to its small size. However, except for Singapore, FDI inflow and transport infrastructure variable tend to positively correlate. Japan is both an “importer” and “exporter” of FDI; therefore, the net FDI inflows into the country varied considerably over time with negative net inflows in 2006 and 2011. Among 13 nations in the dataset, China dominates in terms of FDI inflow, attracting $ 347 billion in 2013, up 18% compared to 2012. Although the economic recession in 2008 hit the region quite hard, FDI inflows into most countries in the region recovered very quickly after that.

Regarding trade openness, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia and South Korea has the highest trade to GDP ratio, meaning that trade accounts for a big proportion of these countries’ GDP. The average GDP per capita during the researched period was $12,200 with Singapore, Japan and Brunei having the highest GDP per capita. As for corruption measure, the mean score was 4.1, a pretty low score falling into the category of highly corrupted countries according to the guideline published by Transparency International. Some countries such as Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, and China are known for being highly corrupt. Singapore and Japan are the only two countries having a relatively good record of having low level of corruption.

Result

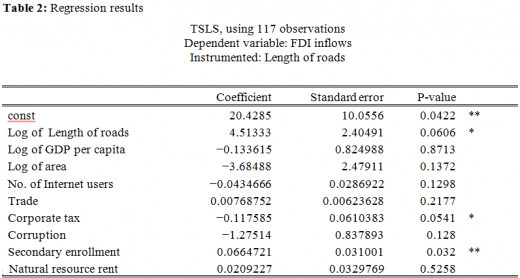

The two-staged least squares technique is utilized to examine the previously specified model. Table 2 presents the regression results. In order to test for the consistency of the estimation to determine whether the endogenous and exogenous variables are valid instruments in the regression, the author conducted the Hausman test to investigate whether two-stage least square or ordinary least square is a better specification for this model. The test statistic for this test - Chi-square – has a value of 32.9. Since the p-value for the test statistic is significantly small, we can safely reject the null hypothesis that ordinary least square estimates are consistent; or in other words, estimation by means of instrumental variables is required. This supports our expectation that there exist an endogenity problem in the model, and transport infrastructure and FDI inflow exhibit a simultaneous relationship.

The result provides interesting insights about the relationship between the dependent variables and other independent variables. Transport infrastructure variable, representing by the log of length of role is statistically significant with the expected positive sign. Empirically speaking, improved transport infrastructure in a country associates with better higher FDI inflows; and higher FDI inflows also create the condition for stronger transport infrastructure development. This finding is consistent with previous research such as Asiedu (2006), Wheeler and Mody (1992).

Corporate tax rate has a significantly negative impacts on FDI inflow, meaning that holding other things constant, countries with higher tax rate will attract fewer FDI capital. Research shows that while the impact of taxation on FDI inflow remains ambiguous (Aldaba, 2006), when firms already narrow down their potential investment destinations with fairly similar investment conditions, tax incentives play a major role in their final decision. Since most countries in the dataset possess similar characteristics in their investment environement, they compete fiercely with one another to provide foreign investors with the most compelling tax policy to draw investment. Another variable that also has the expected sign and is statistically significant is education variable. The result suggests that if everything else equals, countries with higher labor quality will receive more FDI.

Conclusion/Discussion

In the paper, the relationship between transport infrastructure and FDI inflows is tested. Evidence suggests that countries with better transport system and transport infrastructure stand a better chance of attracting FDI. The results also conclude that corporate tax rate and education are also the determinants of FDI inflows into ASEAN plus three countries.

Despite still having some mixed results, the empirical study can still provide some guidance for policy makers as to what should be paid attention to when designing economic policy that also make a country’s investment environment more attractive to foreign investors. Investing in improving the transportation infrastructure will help a country to bring in more FDI, which in turn helps to improve the existing infrastructure. Emphasis should also be placed on providing workers with better training and education. This not only helps the companies to save the cost of doing business but also helps local workers to have high pay and better employment benefits. Besides, when competing with similar location to call for FDI projects, tax incentives may provide a competitive edge, although there is no evidence that the advantage will last in the long run.

Would you consider investing in an ASEAN country?

7 Things you need to know about ASEAN

References

[1] Aitken, Brian and Ann Harrison. "Do Domestic Firms Benefit from Foreign Direct Investment? Evidence from Venezuela." American Economic Review (1999): 605-618.

[2] Aldaba, Rafaelita. "FDI Investment Incentive System and FDI Inflows: The Philippine Experience." International Symposium on “FDI and Corporate Taxation”. 2006.

[3] Arrelano, M. and S. Bond. "Some Tests of Specification for panel data:Monte Carlo Evidence and an application to employment equations." Review of Economic Studies (1991): 277-297.

[4] Asiedu, E. "“Foreign Direct Investment in Africa: The Role of Government Policy, Institutions and Political Instability." World Economy (2006): 63-77.

[5] Canada, Transportation Association of. "Performance Measures for Road Networks:A Survey of Canadian Use." 2006.

[6] Dunning, J. H. Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy. Harlow, Essex: Addison Wesley publishing Co., 1993.

[7] Erdogan, Mahmut and Mustafa Unver. "Determinants of Foreign Direct Investments: Dynamic Panel Data Evidence." International Journal of Economics and Finance (2015).

[8] Goodstein, E. "Jobs and the Enviornment: The Myth of a National Trade-off." Economic Policy Institute (1994).

[9] Johansson, Tulin. "The Interactions Between Economic Growth and Enviornmental Quality: A Comparison of the TVA Region with the United States as a Whole." TVA Rural Studies (2001).

[10] Levinson, Arik. "An Industry-Adjusted Index of State Environmental Compliance Costs." National Bureau of Economic Research (1999).

[11] Lichao, Zhu. The role of Transport Infrastructure in Attracting FDI in China: A Regional Analysis. 2011. <http://www.scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/bitstream/handle/10635/29522/Zhu%20Lichao.pdf?sequence=1>.

[12] Scaperlanda, A. and L. Mauer. "The Determinants of US Direct Investment in the EEC." American Economic Review (1969): 558-568.

[13] Seetanah, Boopen and Jamel Khadaroo. "Transport infrastructure and FDI: lessons from Sub-Saharan African. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa." United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2007.

[14] Tsai, P. "Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment and its Impact on Economic Growth." Journal of Economic Development (1994): 137-163.

[15] UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2014. New York; Geneva, 2014.

[16] Uttama, Nathapornpan. "Foreign direct investment in ASEAN countries: an empirical investigation." 2005ETSG (European Trade Study Group) Conference. 2005.

[17] Vijayakumar, Narayanamurthy, Perumal Sridharan and Kode Rao. "Determinants of FDI in BRICS Countries: A panel analysis." International Journal of Business Science and Applied Management 5.3 (2010).

[18] Wheeler, D. and A. Mody. "International investment location decisions: The case of U.S. firms." Journal of International Economics (1992): 57-76.

[19] Zheng, P. "A Comparison of FDI Determinants in China and India." Thunderbird International Business Review (2009): 263-279.