What Should We Do About Forest Fires in the USA?

Evolving management philosophies

Many centuries ago, Native Americans practiced firestick farming in our forests, in order to increase natural food plants for populations of game animals like deer and elk. During cool moist weather, they set fire to the understory.

This had an interesting side benefit. These fires burned mainly in the duff (dried leaves and other forest litter), and consumed fallen tree branches. This practice decreased the load of easily burned fuel, and prevented highly destructive fires during hot dry weather the following Summer.

The European-Americans who came later did not understand the ecology of fire. This led to tragedies. Loggers in the Midwest were keen on maximizing lumber production. They did not understand the long-term need to burn the logging slash (mainly sawed off tree limbs) in a safe and timely fashion. The result: mega forest fires, which killed thousands of people.

The worst forest fire in the history of the USA was the Great Peshtigo Fire of 1871 in Wisconsin and Michigan. It burned 2400 square miles and killed more than 1200 people. The causes were drought, high heat, and especially land use practices that did not take fire danger into account.

A safe method for disposing of logging slash is to move the tree limbs into one (or more) manageable piles in the cleared area. Then cover most of the pile with plastic, and let the wood dry out. Return in the Fall shortly after after the first good rain. Poke a hole in the plastic at the top of the pile in the center. Add kerosene. Light it with a match. Then babysit your slash burn, shovel in hand. I know about this, because I've done it.

The same principle applies to trees that you've cleared to create either farm land or a railroad right-of-way. Of course, people back then did not have clear plastic sheets to work with. However they could have taken reasonable precautions if they had known about the danger.

Anyway, Peshitigo and other mega-fire tragedies in the upper Midwest was the historical impetus for the US Forest Service policy of aggressive fire suppression through the middle of the 20th Century.

It seemed like a good idea at the time. But there were unintended consequences.

Example: The population of the keystone tree species in Sequoia National Park decreased. Why? Because periodic small fires in the past conferred a survival advantage on Giant Sequoias over competing tree species with thinner bark.

Moreover the larger load of fuel on the ground gradually led to bigger and more destructive forest fires over time.

These days, we have a much greater understanding about the ecology of fire. Even though the zillions of tourists who flock to Yosemite every Summer don't appreciate it, there is now a controlled burning program in this iconic National Park.

I'm not saying that fire suppression is always a bad thing. Many big forest fires are man-caused.

Some examples. A careless driver flicks a half-burnt cigarette out his window into the forest. People using chainsaws without spark arresters to cut dead-and-down trees for firewood sometimes contribute to the fire hazard. There's also deliberate arson.

If we laid off all of the ground crews, our precious forests would receive a huge overdose of fire, which would dramatically increase particulate air pollution in some areas, endanger people in nearby communities, increase soil erosion, create horrendous eyesores, and destroy millions of board-feet of merchantable timber.

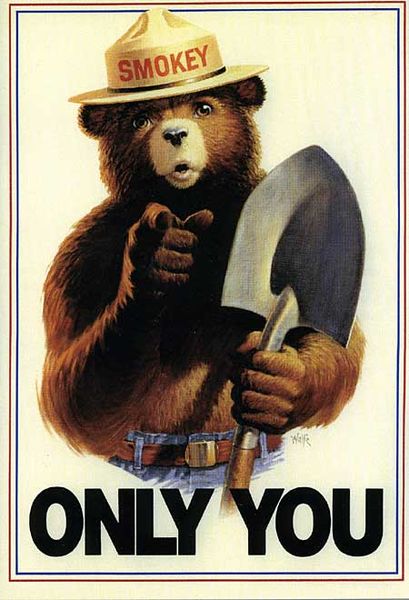

Many years ago, Smokey Bear was the symbol of healthy forests. His famous motto:

"Only you van prevent forest fires."

However the underlying theme was: All forest fires are bad. In light of our present understanding about fire ecology, Smokey's message is out of date. Some lightning strikes should be allowed to continue burning, unless they get out of hand. Some forest areas can even benefit from controlled burns. First and foremost, we need to protect the lives and property of people who live in or near our forests. We need to strike the proper balance between total fire suppression and letting Nature do its thing. We are striving for a balanced fire management policy. And that effort is a work in progress.

Timber Stand Improvement

When the funding is sufficient, TSI is almost a no-brainer for many district rangers in the Forest Service. Why?

In places, the density of young trees is too high. Such dog hair thickets are more vulnerable to fire than mature stands of timber with wider spacing between trees. Dog hair thickets are also more vulnerable to Bark Beetles. A few years after the insects kill the small-diameter trees, they dry out to become over-sized matchsticks.

The solution? Do a thinning operation. When the young trees are farther apart, they are less tempting to Bark Beetles, and less vulnerable to fire. And since the competition for water and sunlight is less, they grow more quickly. Sometimes the ranger district will hire a TSI crew for the Summer. At other times, they'll take competitive bids on these projects.

My understanding is that TSI is often underfunded when Federal budgets are tight. In that respect, it's similar to funding for public libraries, when counties struggle with budget crunches.

What's the most productive approach to forest fire management?

The nuts and bolts of fire fighting

Many years ago, during one of my seasonal jobs with the Forest Service, we flew in by helicopter to put out lightning strikes on the Kern Plateau, just South of the High Sierras in California. The contrast was interesting.

We were transported by expensive sophisticated machines. Then we put out the relatively small fires, using low-tech tools, like shovels and Pulaskis. The latter is similar to an axe, but the head of the tool has an axe blade on one side, and a small hoe blade on the other side.

In retrospect, this effort was probably overkill. Lightning tends to strike trees on ridge tops during small storms, which make the ground wet. And the slow-moving ground fire burned downhill.

In contrast, fires that burn uphill preheat and dry out the fuel above the fire. This is why forest fires travel faster in the uphill direction.

This is also why crews on the ground fighting a large fire, will typically start their fireline at the base of the fire, and then progress up the flanks.

If necessary, air tankers will drop water on the uphill head of the fire, in order to slow it down, and buy time for the crews on the ground. Fire retardants like DAP (diammonium phosphate) may be added to the water.

In building a fireline, ground crews--and bulldozers when they can get in--will cut the brush and trees, and then scrape the duff layer down to bare mineral soil. This prevents the fire from spreading along the ground.

On very hot dry windy days, there is sometimes a risk that the fire will travel in the treetops, and jump across firelines. This extremely hazardous situation is called a crown fire.

Wind is another risk factor for people who fight wildfires. Even when the terrain is flat. Suppose that the fire starts when the wind is blowing in one direction. Then at 3pm, the wind suddenly changes direction, and 'pushes' the fire away from its previous direction of spread. A formerly safe flank can instantly become the new head of the fire. And crews working there may need to evacuate quickly.

That's why it's important to keep tabs on what the wind is doing. If the fire is a multi-day project, the crew leaders should become aware of the local daily wind patterns, so that they can be proactive about the safety of the people they supervise.

After the fire has been completely surrounded with fireline, it is said to be contained. However that's not necessarily the end of the story. For example, asmoldering pine cone could roll downhill, and start a secondary fire below the fireline.

For this reason, shallow trenches may be added to reinforce the lower part of the fireline. With luck, they will catch any smoldering pine cones or smoldering logs that roll down the hill.

After containment, the mop-up phase begins. This involves water, elbow grease, shovels, and lots of dirt.

The most dangerous wildfires in the USA are in the hilly chaparral country (dense chest-high shrubs and bushes) of Southern California. In a worst case scenario, a wildfire there can advance faster than a man can run.

Copyright 2013 by Larry Fields