Will China Stumble into the Middle-income Trap?

What is the Middle-income Trap?

According to World Bank’s classification, low-income economies include countries with GNI per capita of $1,045 or less in 2014; middle-income economies, encompassing lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income economies, are those with a GNI per capita of more than $1,045 but less than $12,736; high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $12,736 or more. Based on this definition, as of July 2015, high-income group, middle-income group and low-income group included 80, 104, and 31 countries and territories respectively[1]. Middle income-trap refers to the situation where developing countries manage to move out of low-income status to reach middle-income status; however, once getting there, these countries have difficulty to move up to the high-income bracket.

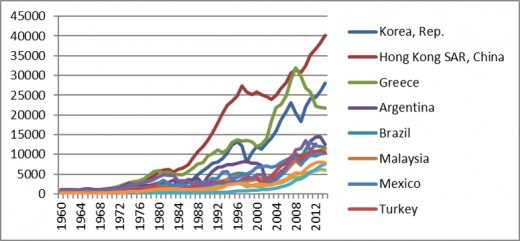

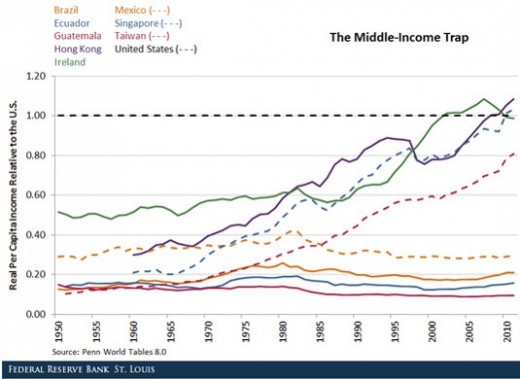

Middle-income trap phenomenon is of great interest to economists because it defies conventional economic growth models, such as the Solow growth model and convergence theory, which state that low-income countries will develop faster than high-income countries, and consequently, all countries will eventually have similar levels of GDP per capita[2] (Barro, 1997). However, according to a study by World Bank in 2012, among 101 middle-income economies in 1960, only 13 had escaped the trap to join the rank of high-income countries by 2008. In fact, these “escapees” are so rare that these economies including South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, etc. are called economic miracles. The very existence of the middle-income trap challenges the theory of convergence and raises the question why some countries are able to make the necessary jump to move up and why some countries are doomed to get trapped.

Conspicuously from the chart, although in the 1960s, these countries had a similar level of income per capita, half a century later, only South Korea, Hong Kong and Greece have safely secured the high-income status. Some Latin American countries for example Venezuela, Argentina, and Brazil fluctuated around the upper-middle income and high – income threshold, but recent economic and political developments in Latin America cast doubt on their abilities to maintain their growth momentum and move forward[3]. For the other middle-income countries, not only do their absolute per capita incomes stagnated, but their per capita incomes relative to the United States’ also languished.

What Causes the Middle-income Trap?

Rising Wages

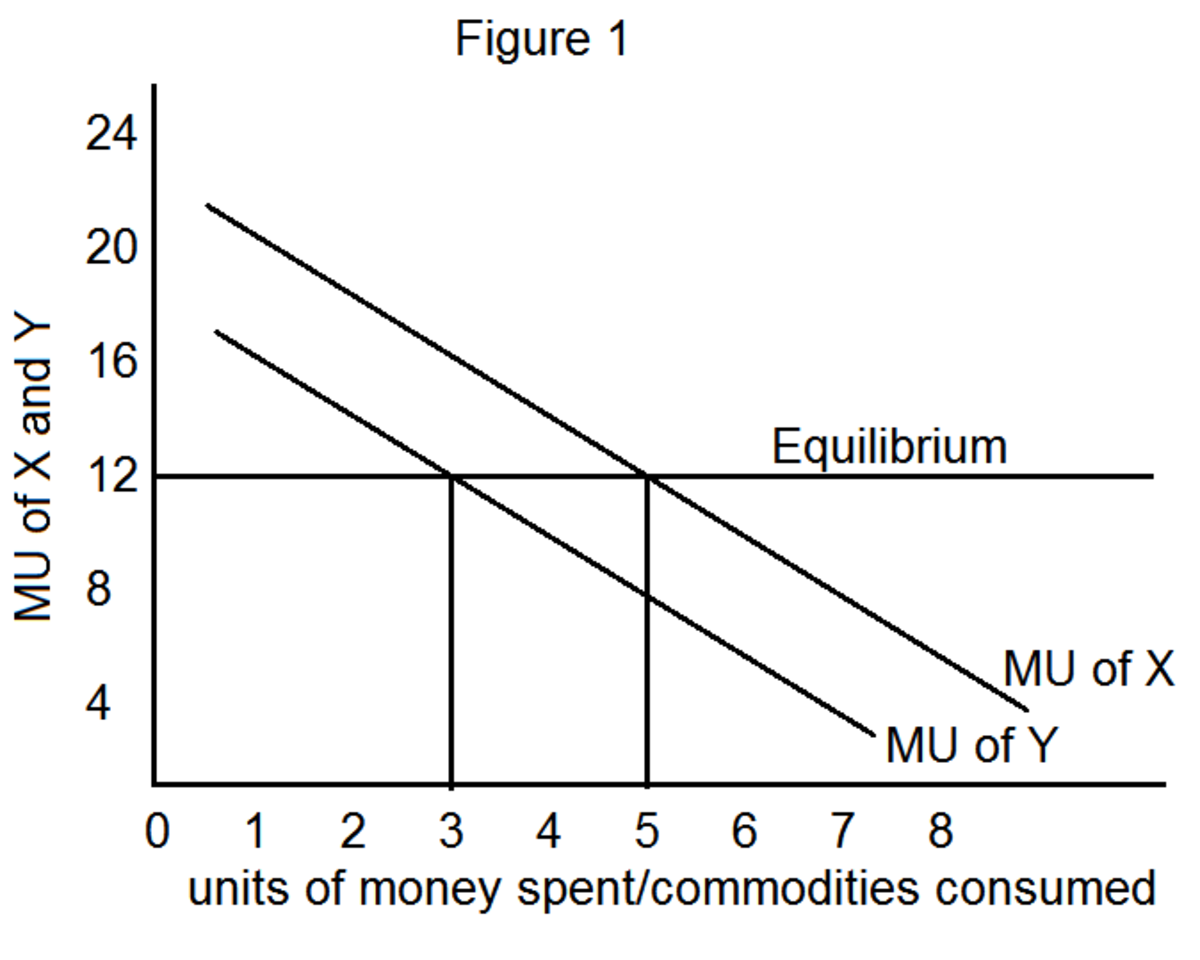

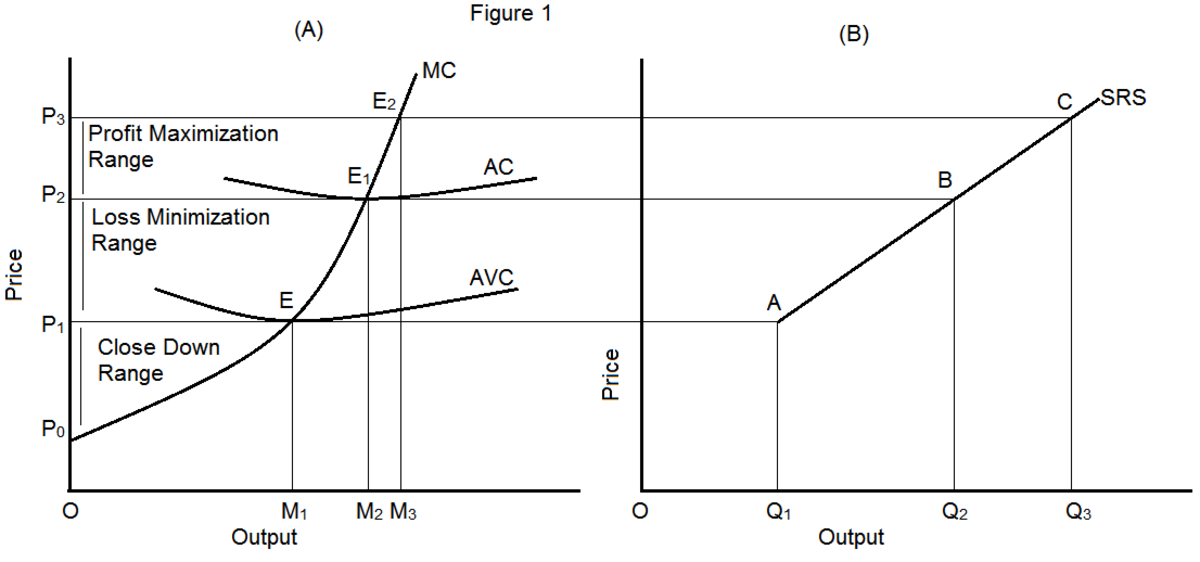

As low-income countries open up their economies to integrate into the global market, investors from developed countries swarm in to invest in these countries to take advantage of the low labor costs and abundant natural resources. The foreign-invested capitals give low-income economies a much-needed initial boost to grow their economies, build up basic infrastructure and improve their people’s living standards. Nevertheless, most newly-developing countries find their rising affluence later poses a problem for them to continue competing as low-cost, labor-intensive nations: they are stuck in a difficult situation in which they cannot compete with either lower-cost countries in terms of cost or high-income countries in terms of productivity and added value.

End of Catch-up Period

The neo-classical growth models developed by Solow (1956), Koopmans (1965) hypothesize convergence property. For example, according to Barro (1997): “If all economies were intrinsically the same, except for their starting capital intensities, then convergence would apply in an absolute sense; that is, poor places would tend to grow faster per capita than rich ones.” Hence, poorer countries will finally catch up with richer nations. There are several reasons explaining for this hypothesis. For example, lagging countries can enjoy higher marginal productivity for every invested unit of labor and capital, receive more foreign investment capitals and assistance, and benefit from knowledge spillover and technology transfer from developed countries. The catch-up period is characterized by high economic growth and major structural changes in developing countries. Unfortunately, if these countries fail to move forward from the imitation period to innovation period, transforming from technology-importers to technology-exporters, they will perpetually fall behind developed countries and the global competition. According to a research by Abdon, Felipe, and Kumar (2012)[4], if a country wants to avoid the middle-income trap, it needs to acquire certain comparative advantages expressed as (i) producing more products and (ii) producing products of higher quality and more sophisticated technology. These characteristics set countries apart, and those fail to acquire these capabilities will end up losing their growth momentum of catching up and remain in their income bracket.

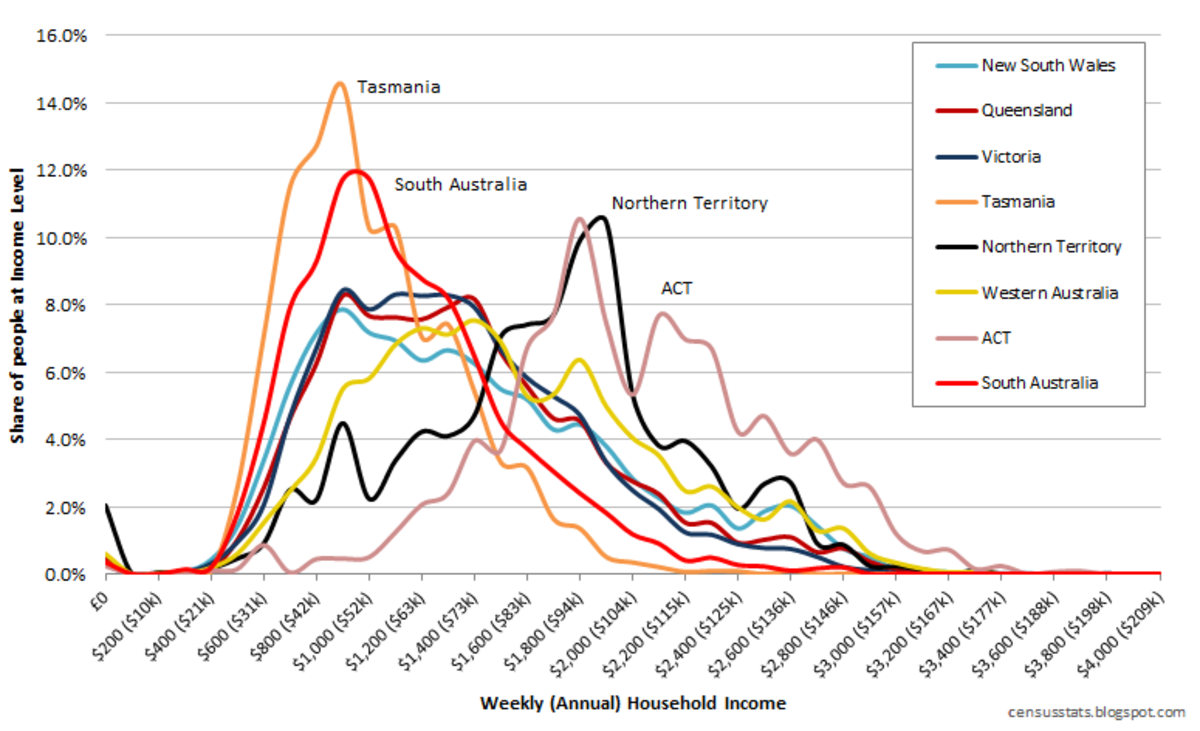

Income Inequality

In the article “Will income inequality cause a middle-income trap in Asia?,” Akio Egawa employed a cross-country empirical approach to analyze the relationship between income inequality and the risk of tumbling into the middle-income trap. He concluded that income inequality, which is an inevitable consequence of fast growth, could slow down economic growth and trigger the trap (2013)[5]. Studying the economies of Taiwan and South Korea, Tibor Scitovsky pointed out that the relatively equitable income distribution in these two countries induced domestic consumption, which in turn propelled investment, creating employment opportunities and opportunities for innovation and improved productivity (1985)[6]. Hence, it is unsurprising that Taiwan and South Korea are two of the few countries that managed to escape the middle-income trap and join the league of high-income countries.

Institutions

According to Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2005)[7], generally, market-supporting institutions will enhance economic growth. Good institutions such as adequate property rights, proper intellectual rights, better rules of law, etc. are fundamental of comparative growth for a nation because they give stakeholders economic incentives to distribute their resources and maximize their interests, thus also maximize national aggregate interests.

The Case of China

Overview of China Economic Growth

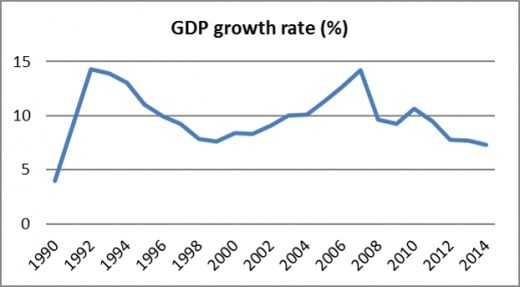

Since China initiated its bold economic reform and implemented market-opening policies at the beginning of the 1980s, the country’s economy has made tremendous progresses, making it the second largest one in the world. In 2014, its GDP reached USD 10.3 trillion, ranking 2nd after the United States, but its GDP based on purchasing power parity actually exceeded that of the United States, ranking 1st in the world. The country’s growth rate over the period from 1990 – 2010 averaged 10%/year, and growth rate has remained above 7% for all years. However, since then, China’s economy showed signs of slowdown, remaining at 6.7 percent in the first quarter of 2016, the weakest growth since the first quarter of 2009. As for GDP per capita, similar to that of middle-income-trap victim countries, although China’s GDP per capita improved over the period of 1960 – 2014, elevating it to the status of an upper middle income country, China is still quite far from breaking the high-income threshold.

Yueh L. (2013)[8] argued that much of China’s economic growth is powered by capital accumulation, labor accumulation, factor reallocation, and “catch up” mechanism representing by transfers of knowledge and technology. Other factors explaining China’s growth include high saving rate, low inflation rate, trade and export openness, increased foreign direct investment and low exchange rate.

In your opinion, will China fall into the middle-income trap?

Will China Stumble into the Middle-income Trap?

China entered the rank of middle-income country in around 2007 – 2008 (Woo, 2011), the years its annual growth rate peaked at around 14%. However, since then, its growth rate continually declined, and for the first quarter of 2016, the economy expanded year-on-year by only 6.7%, the lowest rate since 2007 (some sources claimed that the actual growth rate was only 6.3%)[9]. At the same time, China’s debt as a percentage of GDP over the past 10 years showed an increasing trend, reaching 41.14% as of 2014.

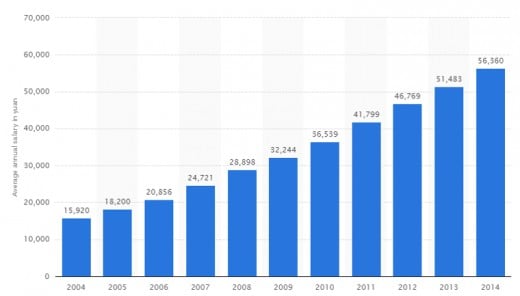

Within this context of Chinese economic slowdown, the question arises whether China manages to escape the trap or meets the same fate that befell many other fellow middle-income countries. One point worth noticing is that wage rate in China steadily increased, averaging 23%/year over the period of 2004 – 2014, and workers in China began to demand higher wages and benefit and better working conditions. Real wage growth has outpaced growth in labor productivity. Consequently, some investors started transferring their investment out of China to invest in lower cost countries such as neighboring ASEAN countries, Bangladesh and even African countries.

Next, income inequality is on the rise in China. China’s Gini coefficient, a commonly-used measure of income inequality has risen sharply over the past three decades, from 29.11 in 1981 to 46.9 in 2014, among the most unequal countries in the world. The economic reform process in China benefited certain political elite group and state-owned enterprises, giving these groups priority over access to political power and market and thus resulting in large state – private sector wage disparity. In addition, Chinese government’s developmental policies also favored some regions such as the coastal provinces, while the interior provinces and mountainous areas received little attention and preferential treatment. Moreover, income inequality between the rural and urban areas was also pronounced. If Chinese government was not able to address this problem, income inequality can lead to massive internal migration within the country, resource misallocation and under-utilization, and social unrest.

Last but not least, as China’s economy expanded and its people’s income grew, concerns about China’s institutions and development models were raised more frequently. The more developed a country becomes, the more freedom it needs to power its growth through changes, knowledge and innovation. In the early stage of catching up, stimulating growth was in the interest of the ruling elite. However, in the long run, the ruling elite might want to discourage further growth by halting growth-stimulating policies for fear of losing their privileges. Consequently, Chinese hybrid economic model might become an obstacle to China’s further economic growth, trapping the country in its current middle-income status.

In this hub, I also detailed some other problems of China's economic transition process.

Conclusion

Wishing to avoid the middle-income trap, in its 13th five-year plan, China has shifted its economic focus to emphasizing domestic market and consumption, clean energy and high technology as well as allowing more competition in national monopoly sectors. If the state government is willing to adopt further economic reforms to foster sustained growth, China can hope to become one of the lucky escapees.

What is middle-income trap?

References

(1) http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups#Lower_middle_income

(2) Barro R., Determinants of Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Empirical Study, MIT Press, 1997

(3) https://www.bbvaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/LatinAmerica_Economic_Outlook_2T15-vf.pdf

(4) Abdon, Felipe, and Kumar. 2012. “Tracking the Middle-income Trap: What Is It, Who Is in It, and Why?”, Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection

(5) Egawa, A. 2013. “Will income inequality cause a middle-income trap in Asia?”, National Institute for Research Advancement, Japan, and Visiting Fellow, Bruegel

(6) Scitovsky, T. 1985. “Economic development in Taiwan and South Korea: 1965-81”, Food Research Institute Studies, Vol. XIX, No.3

(7) Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S. and Robinson, J. (2005). Institutions as the fundamental cause of long-run economic growth. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (pp. 385-472). Amsterdam: Elsevier

(8) Yueh, L. 2013. What drives China’s Growth?. CGC Discussion Paper Series No. 17. University of Oxford.

(9) http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-04-20/china-economic-growth-actually-6.3pc-says-analyst/7341026