Architecture Plan Copying: The Large-Format Camera, Printer, and Plotter

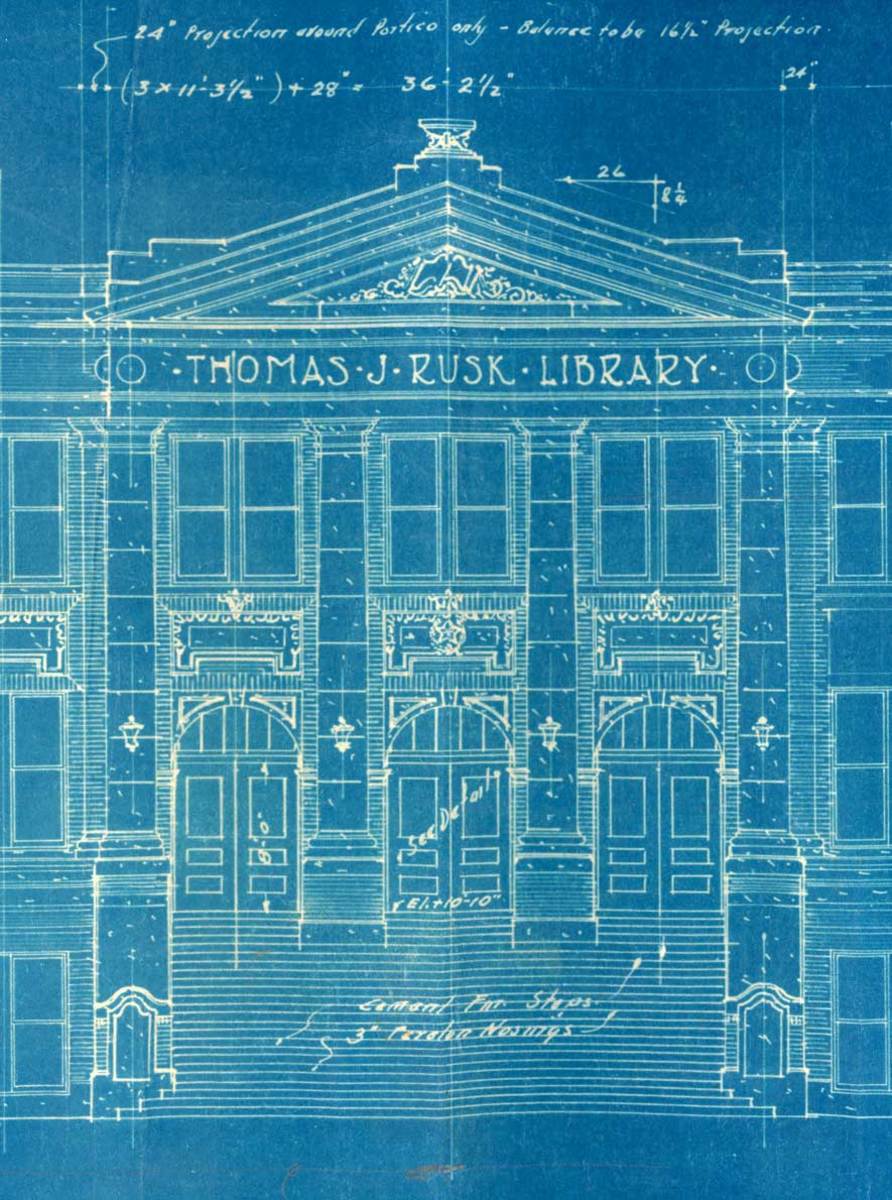

Printing from architectural originals

In my history of reprographics, as explained to me by Ewan Tallentire of Denver's Albion Repro & Graphics, I've covered in Part One the overall timeline of advances in reprographics, as well as types of paper used for originals. In Part Two I explained the advances in the types of paper used for copies. Now let's look at what's happened in large-format printing in the last hundred years or so (I won't go all the way back to Johannes Gutenberg, though some of the pages printed then were certainly large.) Let me tell you about large-format printers, plotters, and the occasional giant camera.

Diazo, photography, and xerography theory

Part Two already discussed the diazo process of printing: you shine light through the original onto a chemically prepared sheet of paper, then develop the image with ammonia. This was the printing method for blueprints, paper sepias, and bluelines.

Photography is similar in that the image falls (by way of a lens) on a sheet which gets developed, but of course the chemicals are more complicated. This printing method used giant cameras and Photomylars.

Xerography is a method of lighting the original over a plate with a static charge on it. The shadowed areas hold the charge, the lit areas dissipate it. The charged areas then attract toner (which is not ink; it's a mix of carbon and polymer), which gets transferred onto and fused onto a sheet of paper (read Wikipedia if you want the really technical details.) This is the standard printing method today, and it uses bond paper.

Side note: xerography in the Soviet Union

An interesting article about perestroika mentions how once the Soviet Union started opening up, one of the changes was the availability of copiers. Previously, you needed official permission to copy things (though dissidents found ways to publish things themselves, leading to the word "samizdat" ("self-published") becoming known in the West. With perestroika, a Western word became a verb in the Soviet Union - xeroxing!

Architectural printers: giant cameras

There's not much else to say about diazo process machines; except to compare them to today's printers, which I will do shortly. First, let me tell you about printing with a giant camera.

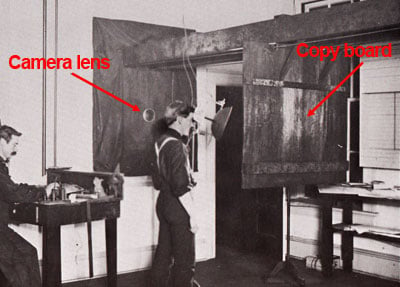

Photomylar was a polyester film with photographic emulsion on it, and it was literally printed like a photographic print, except that it was poster-sized, and the camera was room-sized. Did you know the word “camera” comes from the Latin root for “chamber”, referring to the room between the lens and the film? So you could say that all cameras are by definition room-sized. But the camera in the reprographics shop where Ewan worked, really was. That was why it didn't really look like a camera (neither did the camera for the Rocky Mountain News in the picture below); it didn't have a box around it to shut out unwanted light because the room it was in took care of that.

The camera in Ewan's shop stood about 8 feet tall and was about 10 feet wide. It was about 30 feet from the camera lens to the end of the metal beams that held the big piece of glass called the copy board. The camera had two doors; an opaque one and a glass one. The original would go on the copy board, and the film would be vacuum-formed onto the opaque plate door.

The lens would be set to take the picture at 50%, and the negative would be exposed. Then the opaque door got opened, the glass door got closed, the Photomylar got taped onto the copy board, and a light box was rolled into place behind the negative to expose the Photomylar at 200% (in case you weren’t paying attention, 50% x 200% = same size as the original.)

The shop also had a darkroom for developing the prints. The negative and prints were developed with the same developer, fix, and wash bath as regular photographic film and prints, but the tray was much larger.

The most impressive thing about the camera is what happened when it hadn’t been used for years and nobody wanted to buy it. It was sold for scrap metal, but first it had to be taken off its mountings. You'll have to imagine the giant camera crashing to the concrete floor when the last bolt was loosened. Ewan got a video of it, but I have to wait to see if a friend can put it in web-compatible format.

Room-sized camera

Architectural plotters vs. printers

Now we get into the modern printers. And plotters. Aren't plotters printers, you may ask? Well, sort of. A plotter is to a printer as the printer on your work desk is to the office copier down the hall. It's a cheaper machine used to print one copy of a file at a time; these days, the purpose is usually to check a drawing before printing many copies. Printers cost more than plotters (these days, about 10 times as much as a comparable plotter) and go faster. They're used for printing in volume.

Plotters and printers really aren't that distinct since a plotter of today works easier and better than a printer of a few years ago. (You could probably say the same for desk printers and office copiers.) Most of these machines are made by a few companies, which tend to specialize in either plotters or printers. The major players for plotters are Canon, Ricoh, and HP; for printers there are Xerox, Oce, KIP, and Ricoh. Ewan had some recommendations based on his experience with these companies; I'm planning a separate article about that.

Architectural plotters: what are they?

Plotters came about when architects started working on computers with CAD. The first plotters were pen plotters – literally a pen held over the paper and spatially directed by the computer. They were fun to watch as the paper moved back and forth while the pen drew a circle; the pens drew one way and the paper moved at 90 degrees to that direction. See the video below for a pen plotter in action (it's not large-format, so only the pen moves, not the paper. But you get the idea.)

The pen plotter worked faster than drawing by hand, but not all that much faster. It was precise IF the computer had the right information. And it was overcome by the next generation rather suddenly. Ewan tells of making deliveries of pen plotter pens to customers 10 times a week in the early 1990s. Yet by 1995 the shop was hardly selling pens anymore. By 2003 if you mentioned pen plotters, people would say, “Oh, yeah, I remember pen plotters.”

Today it seems pen plotters are making a bit of a comeback for artists seeking a different look for printouts. (And just for fun, here's a video of a Lego block pen plotter!)

The next step for plotters was the black-and-white inkjet type. Today those first inkjets seem slow, but they were ten times faster than pen plotters. This was the point at which T-bond paper (see Part One) was developed as a cheap(er) way to see a drawing on a big piece of paper instead of a small computer screen. It made sense to check whether your drawing was correct before investing in vellum prints and a full set of copies.

Plotters are still inkjet, but now they print in color, which is important for some kinds of maps and landscape drawings.

Pen plotter entertainment - just watch this pen plotter demonstrate what it can do

Architectural printers: recent advances

Printers are for mass production. Their prices have dropped greatly in the last few years, but they probably won’t replace plotters in small offices unless the price drops a lot more. Large companies can afford their own printing facilities. But though it's possible, it's not yet common for every independent architect or small contractor to have a printer. The speed and ease of use have improved, but not as much as the price.

Over the last 100 years, machines that shone bright light on blueprints or bluelines, then exposed them to ammonia vapor, became more automatic, but stayed the same in theory even into the 2000s. Meanwhile, over the last 20 years, the printers that brought the xerographic process to large-format printing improved greatly.

The major improvement (that has changed the reprographics industry!) in recent years was printers being able to print from digital files. Suddenly it was easy to print out only the pages needed, saving both paper and money. The capability has been there for a few years, but it's really taken off only since 2008 or so, when the recession forced contractors to look at every way possible to cut costs, so sending the plumbers courtesy copies of pages they really didn't need, went by the wayside.

Architectural printers: performance of blueline machines vs. analog vs. digital printers

Let's look at how printer performance has changed. Ewan was working in reprographics back when the only option for construction sets was bluelines, and the machine wasn’t very automatic. Staff had to carefully line up the original with a sheet of blueline paper, feed the two into the machine together, pull them out and separate them, then stack the original in a pile while feeding the copy into the developer. Then run through the pile all over again for the next set.

The science of motion study was needed to do this repetitive process well. Ewan learned to do it left-handed because the rest of the staff was left-handed – with that set-up, they could trade out the work if one was called away to other tasks. Ewan held the shop record for running 1500 prints in one 8-hour day; about 3 prints a minute.

Later, the shop got some analog copiers (printers that copied to bond but without making a digital image, like office copiers of two or three decades ago). With a good operator in constant motion, the analog copiers could run 4 prints a minute.

Digital printers aren't much faster if you're scanning one copy of an original. But if you're working from a file, a digital printer such as Ewan's KIP 5000 can do 8 prints a minute - twice as fast as just a few years ago. (It's a long way from the slap-slap-slap speed at which an 8.5x11 printer can spit out paper, but it gets more impressive when you look at how many square feet are coming out.) And there isn't any physical labor involved, or really even supervision. You just click the mouse, then go do something else until the printer's done.

Architectural printers: space required

Today’s printers also save a lot of space. The machines themselves may or may not be smaller than older machines (especially if you have one of the add-ons that folds or staples for you), but they can print 10 sets of 20 sheets already in order, in no more space than the machine itself takes up.

Analog bond copiers could print 10 copies of the page that was fed in, but then the operator had to take the sheets and stack them in 10 piles. In the right pile. In the right order. Turned the right way up. You had to have detail-oriented workers to run a reprographics shop! Also, to do that job, the shop would need table space for 10 poster-sized piles of paper.

Blueline machines had all those disadvantages and one more; the original also had 10 times the potential for damage, as it went through the printer once for each copy.

Who uses architectural printers?

Assuming you had the money to buy it, would buying a printer save your business money?

The future of reprographics

As technology speeds up some aspects of duplicating, it introduces problems that never existed before. Now reprographics shops have to deal with architectural software instead of all originals being on paper. AutoCAD dominates the market for drafting software, and with each new version, compatibility issues create problems that could have long-term effects on architectural record-keeping. But overall, the software, the printers, and the supplies seem to be moving to more standardization and interchangeability, which is good news for the average architect.

A couple decades ago, when Ewan started in the industry, a small reprographics shop needed blueline printers, some system to print on Photomylar, and a plotter. Now a shop needs less hardware (probably just a printer, a scanner, a plotter) but more software (on-line plan rooms and FTP sites, while perhaps not yet essential, are becoming common).

As in-house printing comes within reach for many small architect firms and contractors (though there are hidden costs that I plan to cover in another article), many reprographics businesses have had to close or focus on the customers with a need for special expertise. For instance, you'd probably seek out a professional for a complex printing job, for building your own house, or for ancient, fragile, originals. There are still such shops out there, but their number has declined.

The industry of reprographics is changing greatly, but the function of reprographics isn’t going anywhere for now. People still want solid copies for record, and though emailing files works for many purposes, computers and construction sites just don’t go well together. Until there are screens tougher and more dust-resistant than paper, that can show 24x36 plans at full size and good resolution, there will be a need for architectural copying. So it's nice to know that the industry has come a long way from the days of copying construction plans by hand.

Previous articles in the series

- Architecture Plan Copying: A History of Reprographics, or, Why Blueprints Aren't Blue Now - Part One

Timeline of reprographics paper and machines used; details on the types of paper used by architects for drawing originals. - Architecture Plan Copying: A History of Reprographics, or, Why Blueprints Aren't Blue Now - Part Two

Details on how and why the types of paper used for making copies have changed.

Related article

- In-House Blueprint: Comparing Xerox, KIP, and Oce Printers

Comparison of Xerox, KIP, and Oce printers based on 18 years of experience in wide-format printing