Tengu - Heavenly Dog with a Nose for Trouble

What is the Tengu?

Unlike some other characters and creatures in Japanese folklore, the Tengu is a purely supernatural being. It has a complex origin and seems to have been the combination of a Chinese spirit (Tiangou) and a demonic bird of prey. In its original Chinese form, it was a canine monster resembling a comet or a meteor, hence its name, 'heavenly dog'.

Over the centuries, Japanese ideas about the Tengu changed until it transformed into a manlike being with bird characteristics, and even its beak became a long red nose!

I first became interested in this strange creature when I borrowed a book from the children's section in my local library, entitled 'Dragons, Unicorns and Other Magical Beasts' by Robin Palmer. It features a retelling of a Tengu story.

I borrowed this book many times from my local library. Years later, the library was selling off old books and I was really lucky to spot a copy, in good condition because it was from the reference library at another branch. It features a short 'dictionary' of magical creatures, and quite a few retellings of folklore about them, including a story about the Tengu.

You can get this only as a used book, as it was published in 1966 by H. Z. Walck, Inc. The one I have is by Hamish Hamilton, London, published in 1967, with a different dust jacket illustration.

Origin of the Tengu

The first recorded reference in Japan is in the Nihon Shoki (720 AD) where the appearance of a shooting star (called a 'heavenly dog') was followed by a military uprising. You can see a later artist's interpretation of this early Tengu, in the next section below.

The association between comets or shooting stars (meteors) and disasters on Earth shows a remarkable similarity to ideas in Europe during the Middle Ages. There, comets and shooting stars were thought to be evil omens predicting the downfall of kingdoms. The most famous example is probably the sighting of Halley's Comet before the Battle of Hastings in which King Harold died (as recorded on the Bayeaux Tapestry). His people, the Anglo Saxons, lost the battle and were conquered by Duke William of Normandy and his army, so that England was ruled by the Normans for centuries afterwards.

The Tengu in Japanese Folklore

A Creature of Change

Like the kitsune (fox), the Tengu had the ability to take on human shape, but unlike the kitsune, its shape changing powers had limitations. It always kept its wings and beak, which was rather a give away!

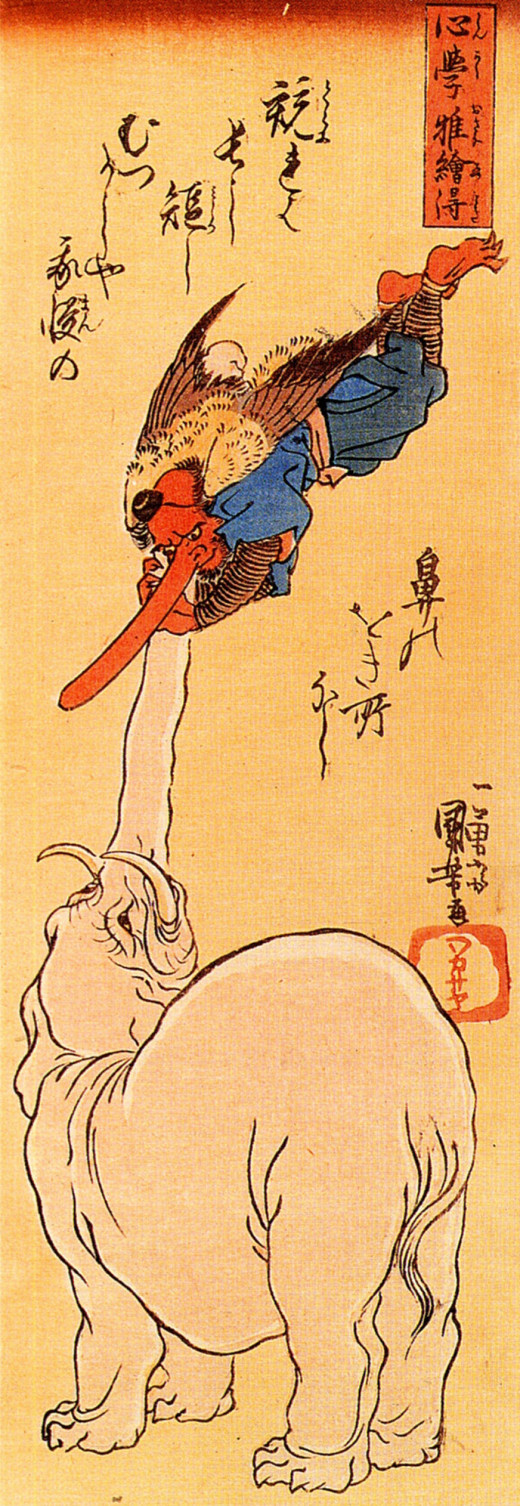

Over time, the beak became transformed into a long nose, and the Tengu was depicted as more human, as in the illustration here.

Early satires in Japan featured drawings of priests, showing them with long Tengu beaks instead of noses, as a comment on priestly moral standards. This may be why a particular caste of priests, the yamabushi, became associated with these strange creatures.

In turn, paintings of the Tengu came to portray them as as men with long noses who wore the characteristic garments of the yamabushi priesthood, such as the little black cap worn on the top of the head. The one being caught by an elephant here is wearing such a cap.

Enemies of Buddhism

Dangerous Spirits

Buddhism in Japan taught that the Tengu were dangerous demonic forces. Minamoto-no-Takakuni, also known as Uji Dainagoft, who lived from 1004 to 1077 AD, wrote a large work called the Konjaku Monogatari, consisting of many volumes. In these, he collected tales from India, China and Japan. In these stories, the Tengu appear as enemies of Buddhism. They often disguise themselves as priests and nuns as they conduct a campaign of harassment, abducting priests whom they then strand in the middle of nowhere, possessing women to try to seduce priests, and robbing Buddhist temples.

One of their troublemaking activities was aided by a type of fan they carried, made of feathers, called the ha-uchiwa (leaf fan). They used this to stir up strong winds.

Later, in the 12th and 13th centuries, Tengu became identified with the ghosts of priests who had fallen by the wayside in their moral or religious duties. They continued to possess women to further their evil aim, and also inflicted the royal family. In fact, the Emperor Sutoku, who first was deposed by his father and then suffered defeat in battle against a later Emperor, swore as he died that he would haunt Japan, and returned to do so in the form of a monstrous Tengu.

As Buddhists, such spirits could not go to Hell, but they could not go to Heaven either, given their bad behaviour. They were filled with enormous pride, so a person who is full of their own importance is still described as 'becoming a Tengu'.

Tengu as Ghost - Spirits of the Dead

Sasaki no Kiyotaka was forced to commit suicide for giving the Emperor bad advice. Here, his spirit has returned as a Tengu to harass the living, and confronts Iga no Tsubone, in Tsukioka Yoshitoshi's painting, Mount Yoshino Midnight Moon (1886),

As time wore on, the outrages committed by these creatures grew worse as they also kidnapped young boys. Although most of their victims were eventually returned, many were mad (in a state called 'Tengu Kakushi', which means "hidden by a Tengu") or half dead. But the story that follows tells of a young man who was luckier than the rest.

Saburo and the Bored Tengu

A Story from Dragons, Unicorns and Other Magical Beasts

This story comes from the book I mentioned at the start of this article. The summary here probably does not do it justice, but I hope it gives a flavour:

Twin cedars grew tall and close to each other in a valley between two mountains in Japan. Villagers called these Tengu trees and gave them a wide berth, but a young man, Saburo, was brave and curious. His grandmother had told him of the creatures who roosted in the trees and he wanted a closer look.

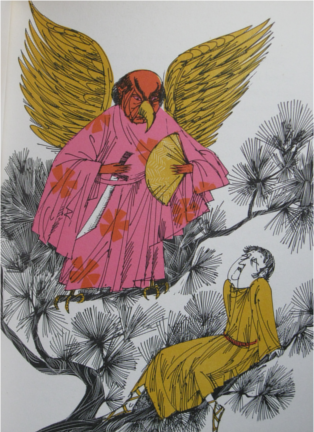

One evening, as he crossed the valley, he was seized and carried up into the top of one of the trees. His kidnapper was a Tengu, complete with feather fan, robe, and wings. The creature's skin was red and he had a large curved beak in place of a nose. He had noticed Saburo's scrutiny of the trees where his people perched, and wished to examine the young man more closely.

Saburo decided to be polite and bowed to the creature as best he could as he clung to the branches. The Tengu, who also wore a sword, boasted how he could kill Saburo by rending him with his beak and claws or running him through with the sword. The creature was bored, with young children to raise, and wanted excitement. Sometimes he got that by setting fire to people's houses and watching them running around to put the fire out.

Saburo said he shouldn't do that. Instead, he, Saburo, would tell stories he had heard from his grandmother. The Tengu decided to spare him for now and gave him the power to fly so that he could help carry the children to the Tengu's palace at the top of the mountain. At the palace, there was no sign of a wife or mother. Food appeared by magic and after the children - small versions of himself - were put to bed, their father asked for a story. Saburo told one after another, some comedies, some ghost stories, some about the adventures of heroes.

At last the Tengu let Saburo sleep, but the young man was worried. His stories would not last forever, no matter how well he spun out the details. He remembered the threats to kill him. But when he tried to escape from the palace, he felt an overwhelming desire to return to his sleeping mat.

Next day, he and the Tengu took the children down the mountain and then they flew off together. At first, Saburo enjoyed seeing the world spread out beneath him. But as they flew for hours, he became very tired. By the time they came to rest on the two cedars, Saburo was so exhausted he could hardly hang onto the branches. The Tengu was amused and told the young man that they would fly twice as far tomorrow.

This went on for days. As Saburo began to run out of stories, he decided he must speak out. One night he told the creature to let him go home tomorrow. He had to see his grandmother to learn more stories. The Tengu said he would consider it, but Saburo must tell another tonight. Fortunately, the young man had saved a very exciting story in the hope that the Tengu would be keen for him to go home and learn more.

Next day, the Tengu said they would set fire to a house. Saburo refused and said he would fly home and never return. This amused his captor because Saburo was not afraid of him. He agreed to let Saburo return home every night as long as the young man flew with him every morning and told stories in the afternoons. He knew Saburo would not be able to resist the compulsion to return that he had placed upon him.

That evening, Saburo was allowed to return home, and his family were overjoyed to see him again. His grandmother told him more stories and asked him to stay, but he knew he would not be able to help himself. Next morning, he went back to the cedar trees and was carried up into the air. But each evening, he returned and learned more tales. Eventually his grandmother's stock of stories ran out, but by then, Saburo and the Tengu were good friends.

As the Tengu children grew up, the young man was allowed more time at home, but he always returned to the twin trees to visit, until he was an old man.

Tengu as Warriors

Sojobu and the Hero

By the 14th century, the Tengu progressed beyond the harassment of priests and kidnapping of boys. Instead, they came to be seen as highly skilled in warfare. This was not because of their early association with comets or shooting stars that foretold human conflict. Instead, it is probably due to involvement in the legend of the great hero, Minamoto no Yoshitsune. When he was still a boy, his father was assassinated by a rival clan. His own life was spared, providing that he went to Mount Karama to become a monk. But while he was there, he met Sojobu, the Tengu spirit of the mountain, who taught him to fight so that he might inflict his revenge.

In early forms of the story, this was the demonic creature's way of causing more death and destruction to humanity, but in later versions, Sojobu befriends the boy because he feels sorry for him. Other stories of helpful Tengu who taught people to fight duly followed, and the image of the Tengu began to be rehabilitated.

Mellowing with Age

The Tengu Becomes an Uncertain Friend

Maybe the Tengu's helpful attitude to the hero Minamoto no Yoshitsune began the change but, with the dawning of the modern age, a transformation began to take place. By the 17th century, these beings began to be seen not as enemies of Buddhism but as its friends and protectors. Now they acted almost as police, to punish priests who did not live up to the moral standards required of Buddhists. A distinction began to form between some Tengu who were still bad and others who could be loyal servants. Yet country people continued to honour customs designed to head off trouble, such as making offerings of rice cake or fish to Tengu, or using mackerel as a protective (and smelly!) charm against them, since they were believed to hate this fish with a vengeance.

The Tengu as Buffoon

Losing its Fearsome Image

Over the centuries many stories were handed down by word of mouth until they were finally collected and transcribed by Japanese folklorists. These stories tend to describe Tengu as fools who are easily tricked by human beings.

By the late 19th century, they could be portrayed as figures of fun, as in this illustration where two of them, delivering post (mail) collide in mid-air, breaking their very long noses.

These Tengu have come a very long way from the fierce bird of prey and war-like heavenly dog of early times, or even the dangerous demons who targeted Buddhist monks in particular.

The Modern Tengu

Reborn in Modern Media

The Tengu has had a new lease of life in modern day fiction such as the children's novel shown here and in Japanese cinema, animation, trading cards and video games. You can see an early silent movie animation below.

Tengu at the Movies - A Silent Movie based on a Traditional Story

In this black and white silent animation from 1929, you can see an adaptation of a traditional story about the Tengu. Although there are only Japanese captions and a music soundtrack, the tale isn't too difficult to follow, especially since the story is available in print on the Internet.

A man with a large boil on his face encounters the Tengu and manages to appease them by entertaining them. As a reward, they remove the boil. Later, he tells his tale to another man, also inflicted with a boil, who tries to win the same boon, but the Tengu are annoyed by his ineptitude and instead they inflict a suitable penalty.

There are various kinds of Tengu in Japanese folklore and It is interesting to see the different ones in this film, with the long nosed human looking yamabushi priest as the leader, complete with ha-uchiwa (leaf fan), bird-men as the standard members of the group, and tiny little ones who serve refreshments!

More Information - Some useful websites

- Tengu - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A useful article, which has a more detailed description of its origin. - Charles C Goodin article

Tengu: The Legendary Mountain Goblins of Japan

Related Material

Are you interested in Japanese folklore or mythology?

If so, you might be interested in my article on the kitsune (fox): Kitsune: Guardian, Lover or Trickster

And please let me know what you think about this article.