24 Reasons Why the "Golden Age" of Japanese Film Really WAS Golden (Part I)

Introduction

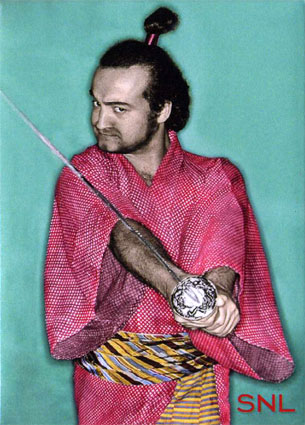

When you hear the words “Japanese movie,” what images come to mind? Probably you think of lovably fake-looking monsters (e.g., Godzilla), or sword-flashing and -clashing samurai… even if only the funny one played by John Belushi on TV. Or perhaps you instantly think: anime, such as Miyazaki’s acclaimed feature-length cartoon Spirited Away (2001). I’m writing this series of hubs as a protest against this unfortunate stereotyping of a great national movie tradition. Don’t get me wrong: I really like Japanese monster movies, samurai films and “Japanimation.” But all these popular genres should properly be perceived as mere parts of a much larger and grander national film heritage.

The Japanese movie industry, from around the mid-1920s to the mid-1960s, established a tradition of quality cinema that, in everything but budgets and box office, was the equal of Hollywood. Badass rebel heroes and gorgeous women, thrilling action flicks and three-handkerchief tearjerkers, slice-of-life dramas and dark tales of tortured psyches, eerie horror and delightful comedy… the Japanese had it all! And for a while, Japan was the most prolific producer of films on earth. Only a small percentage of its total output, however, ever reached Western shores, and of those films, only a handful ever escaped the “art house” theatre circuit to enter popular culture. So almost the entire output of one of the great filmmaking nations remains terra incognita to the average American film buff, and that’s a tragedy… particularly since a lot of this treasure is available on home video.

For this five-part Hub series, the 24 films I’ve chosen belong to the period, lasting approximately a decade and a half (1949-1965), that most film scholars would consider the richest in Japanese Cinema history: the “Golden Age.” During this time, three great generations of filmmakers were turning out classic films on an almost monthly basis. The oldest generation consisted of middle-aged directors whose careers had begun in the 1920s or early 1930s, but who made their strongest films in the 1950s (e.g., Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi, Mikio Naruse and Shiro Toyoda). There was a slightly younger generation that had directed their first works during World War II or slightly later, and which brought a new humanistic philosophy to the Japanese screen (e.g., Akira Kurosawa, Keisuke Kinoshita, Kon Ichikawa, and Masaki Kobayashi). Finally, by the turn of the 1960s, there appeared an even younger group whose formative experience had been Japan’s defeat, and who offered the audience a new ironic tone and a penchant for sex and violence (e.g., Shohei Imamura, Hiroshi Teshigahara and others).

1. Late Spring (Banshun) (Director: Yasujiro Ozu, 1949)

This film, widely regarded as the first of Ozu’s final period (1949 – 1962), not only stands as that director’s most perfect work, but served as a kind of template for all that was to become distinctive and great in Golden Age Cinema. The intelligent script, the obsession with visual style, the polished but subtle craftsmanship, the excellent acting and, above all, the prevalence of character and atmosphere over plot – all these traits appear time and again in the era’s pictures. Setsuko Hara plays a delightful young single woman named Noriko who deeply loves her professor father, a widower (Chishu Ryu), and doesn’t want to marry and leave him. The father, determined that his daughter should be married, pretends that he himself wants to re-marry. This masterpiece includes one of the most haunting sequences of any Japanese film. In this scene, father and daughter attend a performance of a classic Noh play, and Noriko, catching sight of a woman in the audience she thinks her father wants to marry, is consumed with jealousy. Hara powerfully conveys to the viewer the daughter’s complex emotions without a single word of dialogue. In many ways, this is the ideal Golden Age movie.

2. Rashomon (Dir: Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

Over the years, many eloquent words have been written about this classic, one of the most famous in cinema history. Unfortunately, however, most of those words are wrong. A lot of critics still incorrectly claim that the theme of this film – which is about the possible rape of a woman (Machiko Kyo) and the definite killing of her husband, a samurai (Masayuki Mori) – is “the relativity of truth” (whatever that means). But according to Kurosawa himself, as revealed in his autobiography, the film is really about the human propensity for lying, to others and to oneself, and the equally human loathing for seeing ourselves as we really are. The superlative cast headed by Toshiro Mifune, Japan’s greatest star, as well as Kurosawa’s dramatic and dynamic style, ensure that the experience of watching it will never get old, no matter how often it is viewed.

3. Early Summer (Bakushu) (Dir: Yasujiro Ozu, 1951)

This is another masterpiece by Ozu, with Setsuko Hara playing yet another young woman named Noriko. But this Noriko is under pressure to marry not just from one parent, but from an entire extended family, consisting of her brother (Chishu Ryu), his wife and two bratty schoolboy sons, her parents, and an elderly uncle visiting from the country. If I’m tempted to call this movie my favorite Ozu work – with the possible exception of Tokyo Story (see part II) – one reason for this is that the large cast gives the director a chance to demonstrate his remarkable evenhandedness as an artist. Ozu’s films are not about men or women, or about children or old people. They’re about people of all ages and genders, viewed with equal sympathy and insight. The other reason I love this movie is because it contains perhaps the most beautiful tracking and crane shots in all Japanese Cinema – which is truly remarkable because, by the end of his career in the early 1960s, Ozu never moved the camera at all!

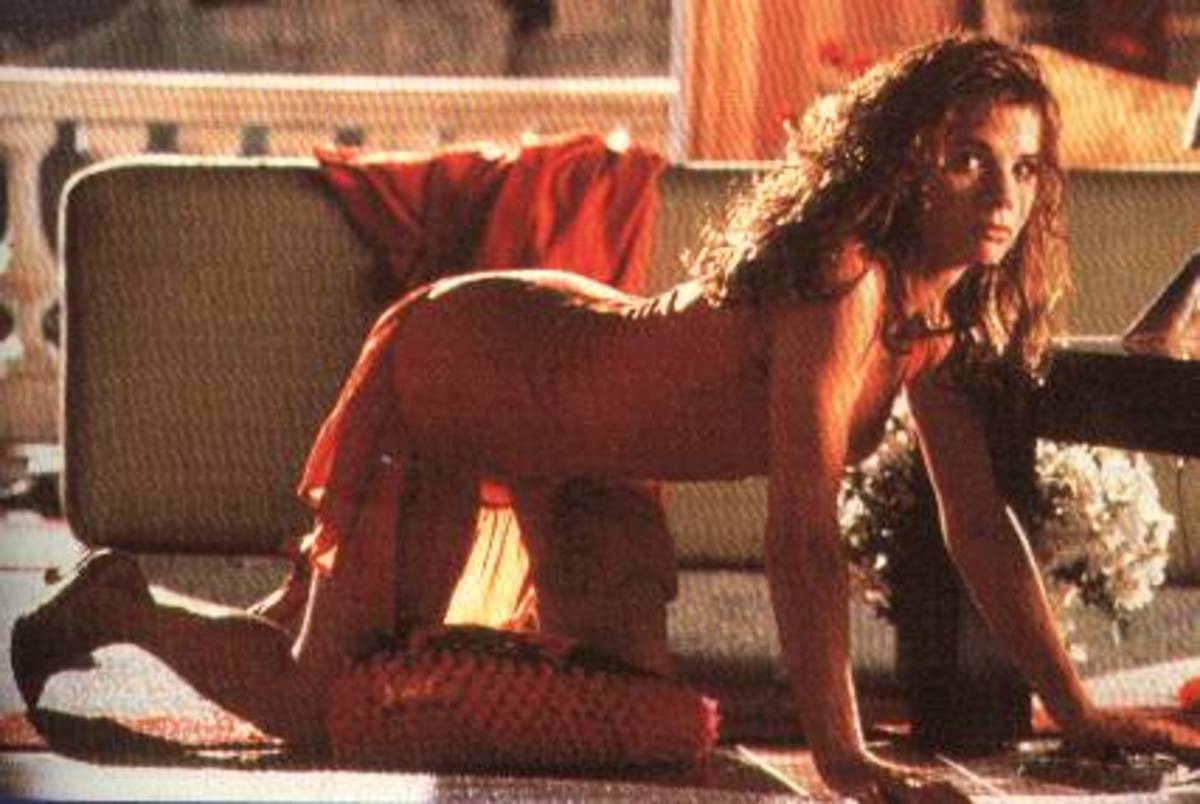

4. Carmen Comes Home (Karumen kokyō ni kaeru) (Dir: Keisuke Kinoshita, 1951)

This more-or-less wonderful musical comedy was the first feature-length color film ever produced in Japan – and though the Japanese were late bloomers as far as color was concerned, they certainly got it right the first time! Little-known master Kinoshita created a film that’s both hilarious and very pretty to look at, but with an undertone of postwar melancholy that’s never entirely concealed. The plot is about a less-than-bright girl (Hideko Takamine) from a remote rural village who returns after having made good in the city – as a stripper. The movie contrasts two clashing types of innocence: the gentle eccentricity of the village folk and the lovable silliness and pretentiousness of Carmen, who insists that her striptease act is “art.” Takamine, who is cast against type here (she usually played smart, thoughtful, modest young ladies), is utterly delightful in the title role.

(Continued in Part II)