Beethoven's Opus 73 at 200

Introduction

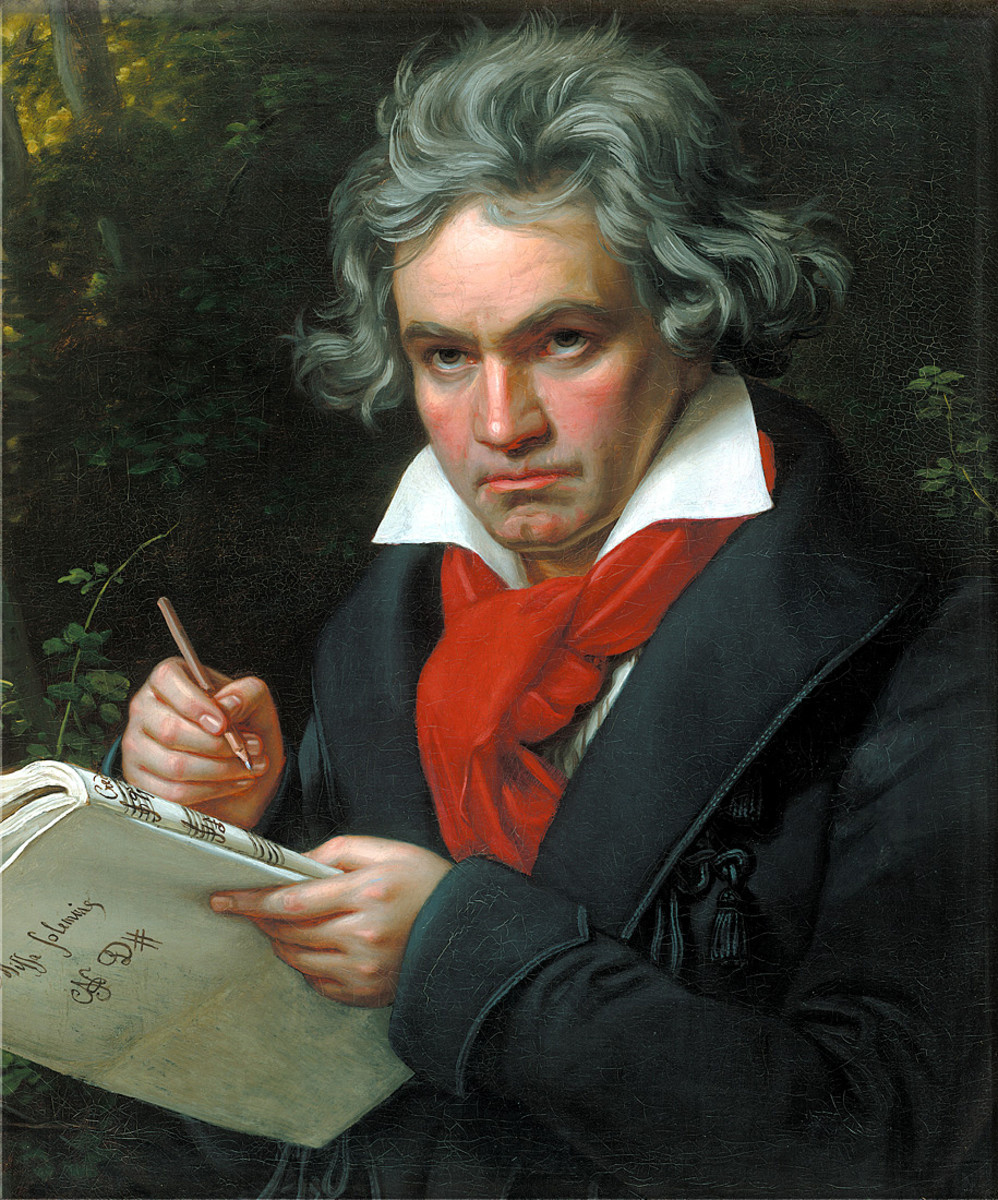

For many people interested in classical music Ludwig van Beethoven has had the reputation of being a curmudgeonly misanthrope, and yet, the second movement of the 5th Piano Concerto reveals a gentle, tender, almost wistful side of the towering genius of Western composed music.

This altogether remarkable piece of music was begun by the composer exactly 200 years ago this year, in the so-called "middle" period of the composer's career, and represents a peak of music written for the piano and orchestra, in my humble opinion.

Nick-named "The Emperor" (not by Beethoven), its full title is Piano Concerto in E Flat Major, Opus 73, and had its not too successful premiere at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig in 1811, with Beethoven himself in his last public performance at the piano. The work was given its first performance in Vienna in 1812 with Carl Czerny, Beethoven's pupil, at the piano, when it got a rather better reception.

- Classical Music for Beginners

If you've always wanted to get into classical music, but don't know where to start this little guide on building a classical music collection for beginners will help. I'm going to assume that you are an...

Development - the three movements

I. Allegro

The first movement is generally a spirited affair, marked "allegro" on the score. It starts with a long chord in the orchestra which the piano answers with a sort of cadenza. This pattern is repeated twice more, in what A.H. Sidgwick in his 1914 book The Promenade Ticket: a Lay Record of Concert-going calls "a sublime piece of comic dialogue."

Sidgwick goes on to describe this "comic dialogue" in more detail:

"Ho!" says the orchestra, on a magnificent chord [E flat major]. "Yes," replies the piano, ranging over four-and-a-half octaves, "but I am also a man of my hands: kindly listen to this little hint of what we are going to do." "Ha!" says the orchestra, on a still more magnificent chord [A flat major]. "Try once more," replies the piano, ranging over five-octaves-and-a-third; "listen carefully, and I will make my hint a little plainer." "Hoo!" says the orchestra, now thoroughly roused [B flat dominant seventh]. "I will just do a trifle more to make it quite clear that I am master," says the piano; "listen carefully; are you ready?" "Yes," answer the strings, pizzicato. "Go," says the piano, and they are off.

The movement is full of interest and the first theme has a distinctly imperial feel to it, perhaps justifying the nickname by which the concerto is commonly known.

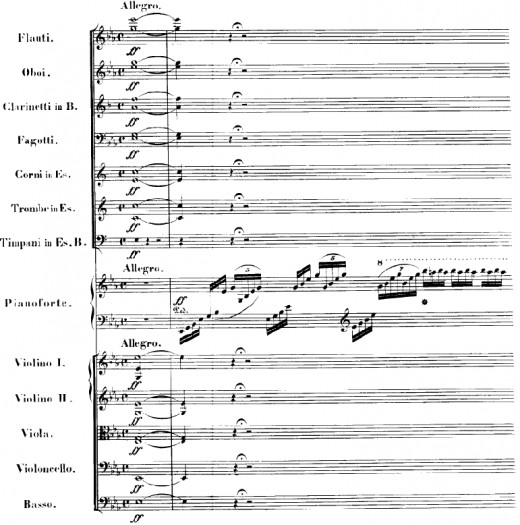

It is a long movement, lasting anything from 17 to 20 minutes, with three themes and lots of piano colourations. Beautiful, lyric notes pour from the piano, with a feeling of spaciousness underscored by the orchestra. Beethoven wrote this concerto for an orchestra of two flutes, two oboes, two B-flat clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani in E-flat and B-flat, and the usual strings. By modern standards quite small forces, but he made every note count in typical Beethoven fashion.

The third theme is played on the piano alone and it brings the movement to a highly satisfactory ending. In fact, it almost seems that the movement comes to an end, and then the solo instrument takes off on another flight again, and again, and again, until the tension becomes almost unbearable and it all finally comes to an end with a few triumphant tutti chords.

II. Adagio un poco mosso

Then the orchestra introduces the theme of the second movement, wistful, ruminative until the piano comes in, picking up and embellishing the theme with gentle pizzicato strings giving punctuation. To quote Sidgwick again:

The theme of the slow movement is beautiful, but something of a relaxation - as often happened in Beethoven's slow movements. No doubt, with the third movement coming, he had to lower the temperature. But it serves as the foundation for astonishing feats by the piano - strenuous and supple and cleanly cut, now meditative, now plaintive, now spirited. The theme is always in the background, but the piano has the front of the stage - which is only another way of saying that it is a Concerto.

The movement comes to a very quiet end, with the orchestra holding a chord seemingly interminably until it makes that famous semitone drop which after a few delicious seconds is dramatically transformed into the thrilling final movement, with no break between the two.

III. Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo

The third movement is electrifying, with dramatic, marching piano chords alternating with brief, quieter moments which only heighten the drama. Again and again the piano makes statements that are answered by the full orchestra, until the piano begins to use short runs upward with the timpani beating a quiet repetitive note, building up the tension until the final glorious chords bring the whole thing to a stunning conclusion.

Sidgwick sums it all up rather beautifully:

This, of course, is only a dull and literal sketch of the main lines of the Concerto: there is endless beauty in detail - particularly the skirmishings of the piano round the theme in the first movement, and the little broken [string] phrases hinting at the return of the theme in the Rondo [bars 319-26]. But, after all, it is a real organic structure, and one has to go first for the main themes, clean and strong and visible as the branches of a beech-tree through all the bravery of spring.

The sublime second movement

Gulda playing!

Coda - some recordings

For many years my favourite recording of this concerto was by Wilhelm Backhaus, but I have long since lost the vinyl LP, and anyway it was wearing through from having been played so much! It was a mono recording and I have not been able to locate it on CD and so have listened to other versions and love in particular the version by Maurizio Pollini with the Wiener Philharmoniker under Karl Bohm. I have also recently discovered the Artur Pizarro version with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra under Sir Charles Mackerras - a really lovely reading.

Also while doing research for this article I came across a reference to a version by Friedrich Gulda which has really captivated me. It is a video of a concert given by the late pianist at the Munich Piano Summer with the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra and the soloist conducting from the piano. It is a revelation. Sure, there are the odd dropped notes and some of the ensemble work is a little rough, most likely because the soloist had to divide his attention between the orchestra and the piano, but the enthusiasm and sheer enjoyment that all concerned seem to have in the performance make up for any imperfections. Its a lively and enjoyable performance.

Finding this performance has been a double delight for me as beside the pleasure of the performance itself, I had never heard before of Gulda, and what a revelation he has been! Seeing him perform the concerto in an outfit that made him look like jazz keyboard wizard Joe Zawinul (they have played together I have subsequently discovered) instead of the more usual tails just was great. And then to discover that the man was also a jazz enthusiast made it all the more wonderful for this jazz junky!

Copyright notice

The text and all images on this page, unless other wise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2010