Citizen Kane: Search for Identity

Citizen Kane: Search for Identity

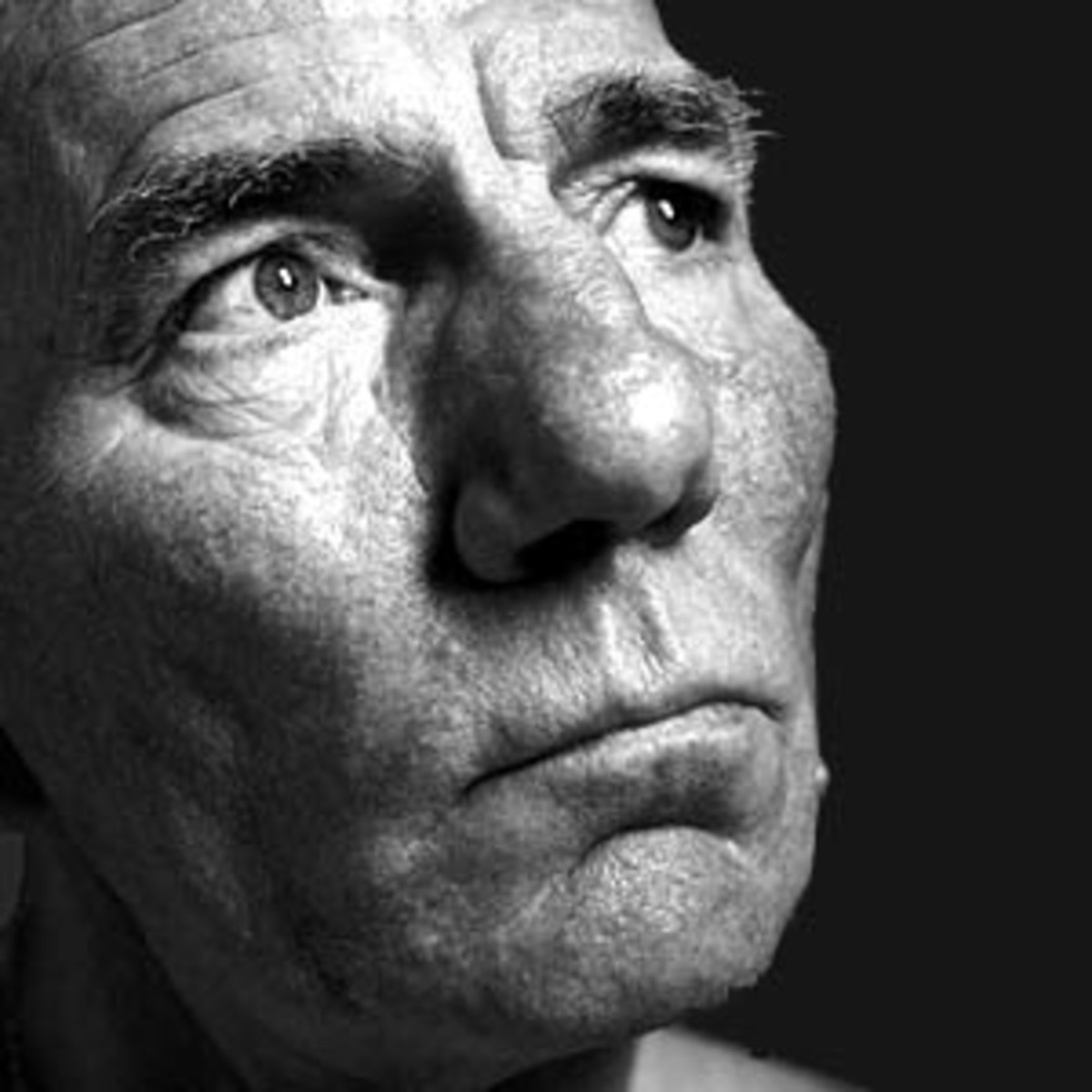

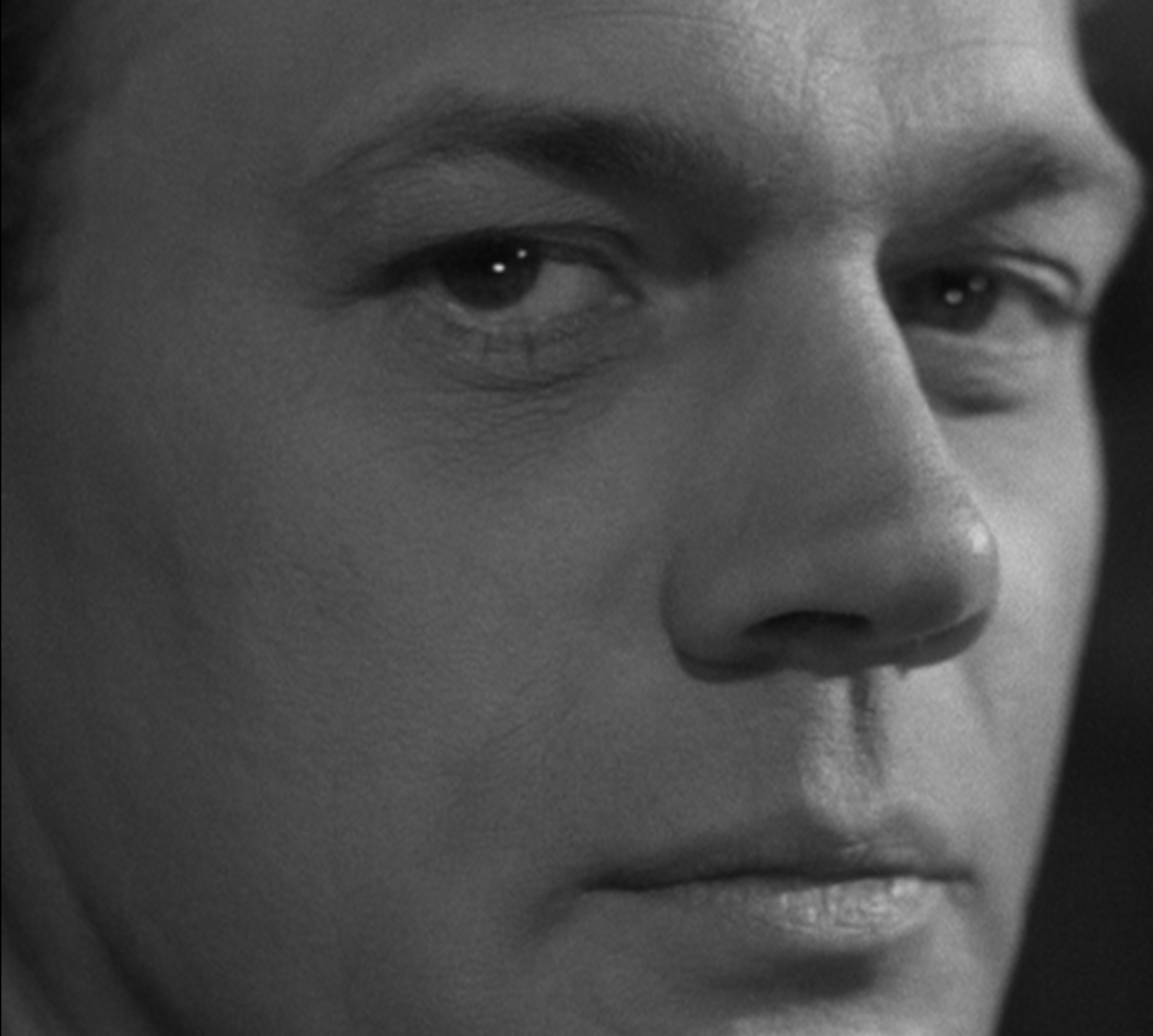

In the film Citizen Kane (1941), Orson Welles uses flashback as a form of narration, in which, while effective, can leave the viewer with differing interpretations of the film, two being, was Charles Foster Kane (Welles) the product of the environment he was sold into, and was his abusive father (Harry Shannon) really the cause of this happening? Throughout the movie, the narrations are the viewpoints of people who knew him. Kane was taken away from the family he loved, and grew a deep resentment towards everything the system he was brought up in represented, but the point is blurred by its interpretation from different points of view. In Morris Beja's article Where You Can't Get at Him: Orson Welles And The Attempt To Escape From Father, Beja’s claim is that Kane was sent away to protect him from an abusive father, grew a resentment towards every thing that might have represented power and the forces that took him away from his mothers love. In Bert Cardullo’s essay The Real Fascination of Citizen Kane, Cardullo points out that this particular story being told, is the point of view of Walter Parks Thatcher (George Coulouris), being read out of his memoirs. While both pieces bring out interesting points, one would have to believe that Cardullo holds the more accurate picture simply by pointing out the unreliability of Thatcher's testimony coming from his own biased opinion.

Orson Welles, who directed, and starred in the role of the adult Kane, shows reporter Jerry Thompson (William Alland) going through Thatcher’s memoirs trying to find information on Kane. The scene changes to a flashback of when Kane was eight years old, playing in front of his parents boarding house. The young Kane (Buddy Swan) is in his innocent years, as was America prior to becoming a world power. In Morris Beja’s article, Beja portrays young Charlie as “deprived of his mother.” The article references other works by Welles where the father is portrayed as an antagonistic figure. Beja starts out his article stating,

In Orson Welles first film, Citizen Kane, after young Charles Foster Kane pushes the adult Walter Parks Thatcher down in the snow with his sled, his mother protectively holds on to him while his father reaches for him threateningly. ‘What that kid needs is a good thrashing,’ Mr. Kane says: Mrs. Kane’s reply is that it is because he thinks that way that Charles is ‘going to be brought up where you can’t get at him’ (Beja 1).

He also notes that it is the father who is warmer to him than his “cold and calculating mother.” Beja goes on to state that Kane grew a deep hatred for Thatcher due to him being the one who stole him away from his mothers love, and how he aspired to become everything Thatcher hated.

The article continues referencing Kane’s history with women, having his own son taken from him, and changing from the idealistic crusader that he was, to become more like Thatcher himself. At a glance, this all appears to be the truth. Thatcher saw himself as a sort of savior for the boy at the time he took him away. Kane’s parents were unrefined representations of everything that Thatcher stood for, to use and exploit. The child was his banks ticket to the mine the parents had, and as he played in the snow screaming, “Go Union,” young Charlie had no idea he had been sold into that very symbol of the industrial capitalistic world that Union was to become. As the sled covered in snow at the end of the scene, Charlie too, had been abandoned. Beja references Freudian and Kafkaesque paradigms throughout the article citing works by Kafka, and Welles’ claim that as for the use of Rosebud in Kane “It’s a gimmick really, and rather dollar-book Freud.” (Beja 5) What Beja fails to address is that the narrative had been read from the memoirs of Thatcher, from Thatcher’s point of view. Nor did he explain the meaning of Welles’ quote, which he likens to Kane’s statement that he wants to become everything Thatcher hates.

What Welles actually stated was. “I’m ashamed of Rosebud, it was a rather tawdry device, it’s the thing I liked least in Kane, it’s kind of a dollar-book…Freudian gag; it doesn’t stand up very well.” (Orson Welles) Again, Beja omits the fact that this is only a relation coming from Thatcher’s point of view.

Bert Cardullo’s essay offers a different take on the scene. He immediately points out that right after Thatcher’s story about the young Kane is over; Mr. Bernstein’s (Everett Sloane) story begins, with a contradiction of Thatcher. From then on, the film shows several more conflicting viewpoints on Kane. The true story of Kane is never known. Only the public Kane is shown through newsreels.

Cardullo goes on to question the believability of Kane’s mother, Mary’s (Agnes Moorehead) actions. He asks why Welles and writer Herman J. Mankiewicz did not make the scene more believable. He states “Truth is often stranger than fiction, it is said; that does not relieve fiction of the burden of believability either.” (Cardullo 171) While Thatcher is narrating his version of Kane’s life, Cardullo notes, Welles and Mankiewicz are narrating Thatcher, so why do they leave this gaping moral hole?

Cardullo points out that this was not merely a simple oversight on Welles and Mankiewicz’s part. Rather than give the viewer a character study, they offer the study of the “experience of character.” The film is about the “dead” Kane, this gives Welles and Mankiewicz the liberty of using identification through a narrative method in a film about him. “Welles and Mankiewicz ‘clue’ us in that their film is not intended as a character study of Charles Foster Kane because he appears, on screen in Thatcher’s memory, fabricated from the very start, the unnatural product of his mother’s unnatural act.” (Cardullo 172)

A second clue as to the filmmaker’s intentions, Cardullo points out, is the fact that when Kane died, there was no one within earshot to hear him say the word “Rosebud.” The nurse comes in after hearing the noise of the breaking glass, and Raymond (Paul Stewart) was nowhere to be seen. Cardullo asks, “How is it, then, that Jerry Thompson and all his news associates know that “Rosebud” was Charles Foster Kane’s last word?”(Cardullo 174) Cardullo points out that no one but the audience knows this, as well as the fact that that was the name of Kane’s sled. Rose bud is the device used to help the audience identify with the search for who Kane was. This device brings the viewer back to Kane’s youth. Cardullo too, draws on Welles’ quote on “Dollar-book Freud,” explaining that it is a question open to interpretation, as Welles put it, a gimmick. The fact of the matter is that the gimmick works. It draws the viewer back to Kane’s childhood and compels the viewer to try to identify with him.

Morris Beja’s article raises interesting questions about Kane from a psychological perspective. However, what he is arguing against is a fictional character’s relation of another fictional character’s life. He offers analysis of why one person’s life played out, through the writings of another character in the film, where his focus should have been is on the writers and direction of the film itself, the true conscience of the work. His views on Kane, Kane’s parents, and Kane’s life hold no credence unless the article is titled, “Thatcher’s Story.”

This is where Cardullo’s essay holds more merit. Cardullo questions the use of individual narrative from a number of different characters who had different takes on who Kane was. He questions the believability of situations within the film, and the reasons the filmmakers presented it this way. He questions the motives of Kane’s mother for taking the action she did with her only son, and the credibility of the implication that his father was an unfit, violent man. Cardullo realizes that all the characters in the film are just that, characters. We see the characters as we see them because we get to know them through the eyes of the filmmakers, in the narrative present. The essay focuses on not what the film was made to represent, but why the film was represented the way it was. It questions why the film presented a dead Kane, instead of a living one and offers the explanation that Kane was a pathetic character, who did not know what was happening to him. The way the film was made, through other peoples point of view, helped the character to rise above pathos, whereas, telling the story while Kane lived, would have shown only the pathos of Kane, and nothing more.

Works Cited

Beja, Morris. “Where You Can’t Get At Him: Orson Welles and the Attempt to Esacape From

Father.” Literature Film Quarterly 13.1 (1985): 2-9. MLA International Library. EBSCO.

Web14 April 2010

Cardullo, Bert. “The Real Fascination of Citizen Kane.” Before His Eyes: Essays in Honor of

Stanley Kauffman. Ed. Bert Cardullo. University press of America: Lanham, MD 1986.

169-177

Citizen Kane. Dir. Orson Welles. Perf. Orson Welles, Joseph Cotton, Dorothy Comingore.

Mercury, 1941

Orson Welles on Citizen Kane and Rosebud [Video] 2:35. Retrieved April 14, 2010 from