Cancers & Tumors among the Underprivileged in Third-World Nations

Survivability rates are improving

Survivability rates vary widely depending on the location of the cancer, from 3% for pancreatic cancer to more than 90% for thyroid and testicular cancers. The average five-year survivor rate for all kinds of cancer is now above 50%, double what it was in the 1940’s. These statistics are for the USA at large.

Other reasonably affluent countries have similar records, most often correlating with socioeconomic advantage. A study of four types of cancer in 31 countries found that five-year survivability rates were higher in North America, Australia, Japan and Western Europe than in Africa, South America and Eastern Europe. Sixteen of the countries were able to provide data for nearly all of their population, the other 15 providing representative samples.

The report did not conclude—but I would venture—that where cancer records were more difficult to collect, cancers themselves were probably less successfully treated. This applies not only to the 15 countries supplying partial data, but to the rest of the world as well. There are approximately 200 nations, and it is likely that the 31 selected for the report are among the most affluent and the most successful at both diagnosing and treating cancers.

Survivability rates among the poorest nations

Healthcare opportunities correlate with a nation’s economic development. Countries with low per capita incomes cannot offer as high a quality of healthcare to their citizens as countries with higher per capita incomes. There are two reasons for this. First, lifespans are not as great, people dying from other illnesses and injuries, so that not as many live long enough to develop cancer. The second reason is that the necessary technology and specialized medical personnel may not be available.

In the impoverished reaches of many countries, life is hard enough that cancer is simply a self-diagnosis when nothing else seems to fit. It is considered to be a cause of death rather than something treatable. Many remote villages are accessible only by footpath or, at best, unimproved roads that are traversed only by motorcycle or the occasional crowded minibus loaded with passengers carrying produce to market and material goods on the return trip. For these people, a hospital capable of handling routine injuries and illnesses can be many arduous hours away from home, requiring a stay in a town or city at the kind graces of some distant relative or acquaintance. It also means leaving one’s crops, animals, and the rest of the family.

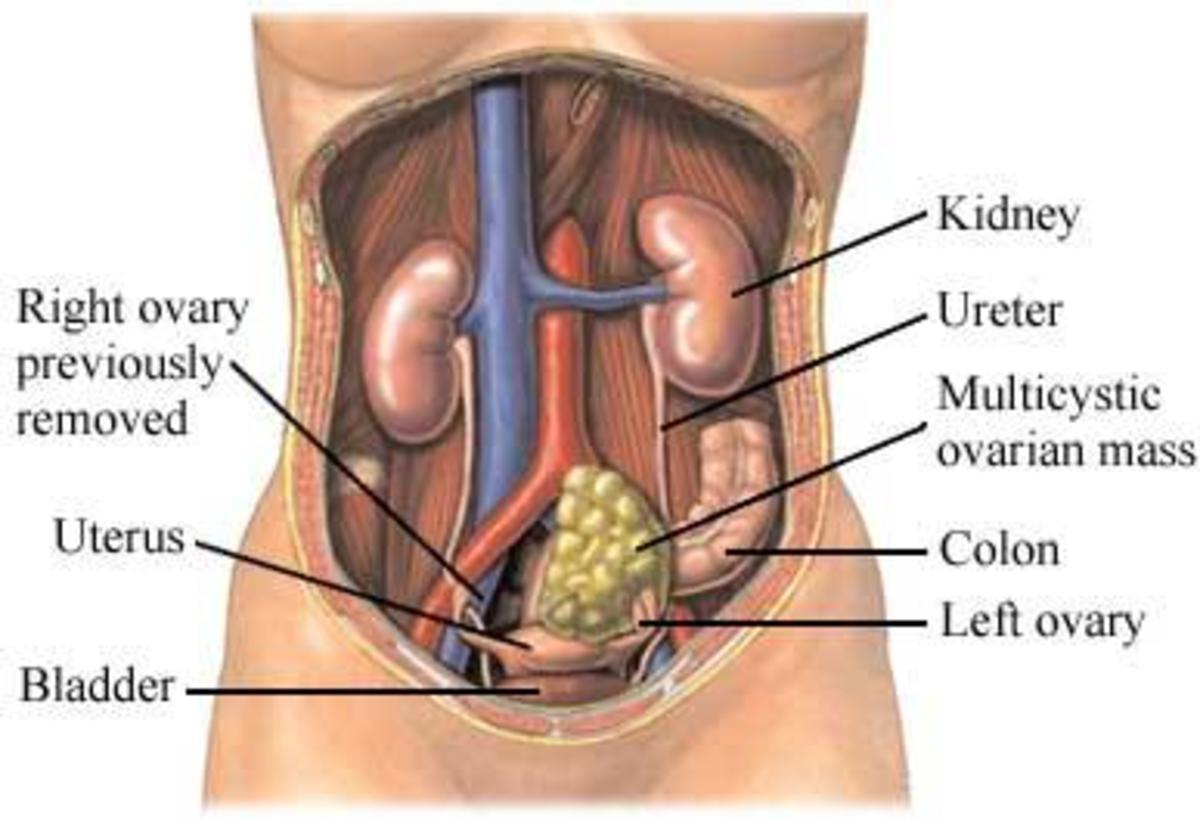

Sometimes the best a hospital in the next town can do is to provide a diagnosis. They may be unable to diagnose tumors and cancers and have to refer the patient to a hospital in a larger city that requires expensive travel by plane, train or boat. Knowing all this, poorer patients often wait until they have tried everything else and are fairly certain that the ailment must be some mortal illness. Going to a hospital at that stage for diagnosis is generally too late to do much good anyway. The doctor confirms that, yes, it is cancer. Even a benign tumor can kill if not removed. The patient goes home with the fatalism of one who knows that they are dying and that there is not much anyone can do about it. Of course, the national news may have reported that someone in the presidential family had a cancer operation, but that goes in the same category as reports that the USA used to send people to the moon. A poor farmer could never afford that.

About the poorest nations

In the year 2000, eight Millennium Development Goals were adopted by the United Nations and ratified by 189 nations, agreeing to achieve them by 2015. They all pertain to improving the quality of life for the poorest of the poor. According to 1990 statistics, 82% of the world’s population lives in countries with a per capita GNP of less than US$500 per year. Similarly, 84% of the world’s population lives in countries with the lowest quality of life in terms of life expectancy, infant mortality and literacy.

As these goals are achieved in the poorest nations, there will be more cancers diagnosed and more cancers to treat. There will be a need for more and better treatments, more oncologists and more cancer research and training programs.