Desolation

By Nils Visser

As I write this a friend has withdrawn into grief. It is not a phase of grief that can be overcome with the help and comfort of others. It is a phase of grief where one walks alone, a solitary odyssey through the mangled ruin of loss and desertion. It is not for me at this moment of time to interfere, intervene or interact, even though I can sense ache and anguish across both the physical and psychological gulf that currently separates us. All that I can do is wait by the exit, and hope that the door will open at the end of a journey through excruciating pathos, for that is not a given.

The helplessness I feel is akin to the time I watched a happy pup bound across the road towards its master and realized with sudden and bottomless horror that the pup was in the way of a speeding pick-up truck. There was time to holler out the dog’s name, time for the dog to grin happily in grateful recognition and then it disappeared under a broad front tire of the truck, half-a-surprised yelp as its final soliloquy. Yet this agonizing inefficacy of mine is a walk in the park compared to the meaningless black pit the friend is trying to make sense of.

As you may have gathered, the bereavement wasn’t a death that can be easily made sense of. It’s difficult enough to explain death as it is. On the one hand it’s as easy as cartoon figures singing about circles of life, for in the end, that’s the essence it all boils down to, our ego and sense-of-self but a brief cycle from the perspective of a wizened tree overlooking a village churchyard for over a millennia. However, for those left behind the gaping existential gap left by the departed; the resultant emptiness and dawning realization we’ll never hear that laugh again, never feel the warmth emitted by that living body again, never see that face animated by the quirks of individuality again cannot be satisfactorily filled with platitudes about natural cycles.

We want meaning, somehow the sorrow seems easier to give a place if there is some sense, some logic, something that can be understood. Some turn to religion, others seek to allocate responsibility, blaming themselves if necessary, for that is far less disloyal than blaming the departed for leaving us to cope with their absence. People try to offer consolation with remarks that the pain will fade, that it will turn into something to get used to. This is a falsehood of course, for the remainder of your life a glimpse of a familiar feature or habitual gesture in a crowd, a smell, a fragment of music or other stimuli can trigger memories and initiate an avalanche of grief. At most, we can give the loss one meaning or another, making it more bearable and take the edge off by means of acceptance, elements of closure or other, less advisable substitutes.

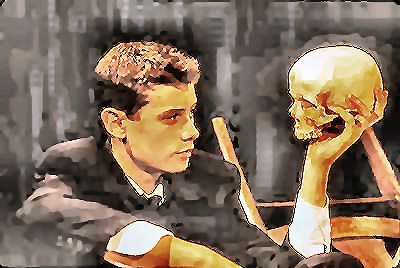

The processes involved in grief aren’t helped by our lack of definitive knowledge regarding an afterlife. Hamlet of Denmark sees our tendency to maintain a tenacious grip on life as a result of this uncertainty: “The undiscover'd country from whose bourn no traveller returns, puzzles the will and makes us rather bear those ills we have than fly to others that we know not of.” Presences may well be perceived and attributed to religious or spiritual causes but yet small nagging doubts may remain, sapping away at the surety of conviction. For how much is projection? How much is the seemingly immeasurable power of the human mind? A self-regulating entity that opens and shuts passages to allow links to be made or severed and creates scope for such subjective perception that we indeed create our own reality. Hamlet spoke of this too, of “thoughts beyond the reaches of our souls” raising doubts: “why is this? Wherefore? What should we do?” Aware of man’s “infinite….faculty” our Danish friend questions reality he previously perceived to be true vis-à-vis his encounter with the spirit of his deceased father: “The spirit that I have seen may be the devil: and the devil hath power to assume a pleasing shape; yea, and perhaps out of my weakness and my melancholy, as he is very potent with such spirits, abuses me to damn me.” In the current context that devil is, of course, the devil that houses within ourselves.

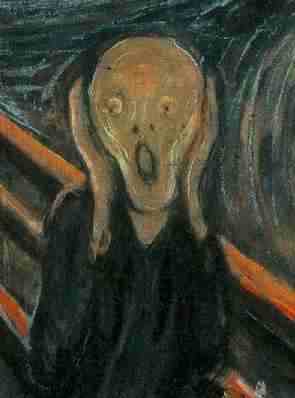

Rarely is such weakness and melancholy more on the wax than during the solitary vigil of grief I have spoken of. Therefore logic and reason are on the wane and the soul is vulnerable to strange flights of fancy that are self-destructive in nature. With no shield of rationale to ward off that which is improbable in broad daylight, these figurative birds of carrion, impervious to mercy, circle their prey and whilst crooning their hideous calls peck and peck away, leaving deep scars on an already wounded soul. This assault on the psyche by vultures that thrive on vulnerability does not occur during sleep, rather the nightmare comes as an enveloping cloud of darkness whilst one is awake and in wake. The sensation is that of being smothered, that of wanting to scream the verbal dregs from the very darkest and deepest pits of our subconscious but at most able only to utter a barely audible whimper. Full awareness of the current turmoil in contrast with the total inability to control the situation as well as the lack of apprehension to sooth oneself by repeating the mantra that the moment will pass. There seems to be no light at the end of the tunnel, seconds turn into hours, minutes into days.

I await word in the light at the end of that tunnel, word that the storm has been weathered and a soul will emerge, battered and bleeding but still intact. This is red-raw bloody grief and there is nought I can do about it, except perhaps accept that it is a path that must be walked, perhaps more often for some than others, but trodden it must be, it’s part of that circle of life, which, contrary to the message promised by advertisers, seldom resembles a rose garden.

If the above is excessively melodramatic then this is not a cheap sensationalist play at emotions, just the inability to find the words to express the mental turmoil of standing at the edge of a precipice of doom and plunging down, the ego shrinking to a diminutive size all the while. That also explains calling in the help of Will Shakespeare, for he never seems to be at a loss for an adequate metaphor to describe the scale of human emotions.

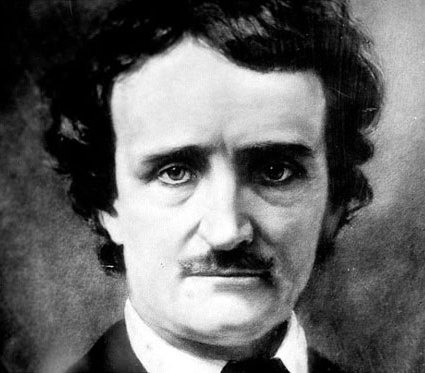

In dealing with loss and being lost, however, there is another. Edgar Allan Poe was no stranger to loss. The primary reaction to his poem The Raven is pleasing because of the alliteration and rhyme scheme introduced in the first stanza: “While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

as of someone gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door”. There is logic to be perceived there, a sensible order and therefore something that can be comprehended and understood. However, all too soon all that structural element becomes but a feeble construction barely able to protect us from the whirlpool of desperation that is overwhelming as it turns out the narrator is struggling with the death of a loved one. The narrator does this by questioning again and again the utter and dire finality of death. Will he truly never see, hear, smell, touch his beloved Lenore again? Upon which that dark raven utters only the word “Nevermore.”

Poignant as this is, a little background information takes it to a truly heart-breaking level that tells us Poe was very familiar with the cerebral quagmire of melancholy indeed. For his beloved wife Virginia Clemm showed the first signs of consumption seven years after they married. She was only twenty years old when she became ill. Poe wrote The Raven, his masterpiece on the grief that follows the loss of a loved one, three years later in 1845. Virginia died of tuberculosis in 1847, aged 25.

This means that Poe was living up to part of Hamlet´s description of the incredible composition that a human being really is. For in the `What a piece of work is man` speech the Prince of Denmark states that man can anticipate the future: “in apprehension how like a god!”

When Poe wrote “take thy beak from out my heart” he wasn’t writing about grief he had been feeling, he was writing about grief he knew was still to come. I envisage him at his writing desk composing pain yet to be as his young wife lay on her sickbed, slowly fading away. I wonder, did he read it to her when it was finished? Was the pain in the poem something Edgar shared with Virginia?

Poe knew the maze of mind’s agony my friend is in, probably resided there too often for he clearly sought to dull his senses and take the edge off the pain -exquisite pain as he called it- and as I fret I share the foreboding oppression from The Raven. Will the exit be found? Will the soul emerge intact? Or will I too plaintively ask for a beak to be taken from out my heart?