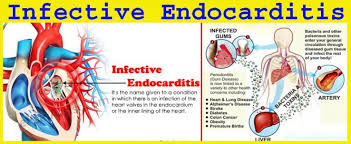

Infective Endocarditis

Mr Smith is a 69 year old male who presents to the Emergency Department with a 3 days history of confusion, lethargy, low grade fever and muscle pain. Tonight he experienced chills, fever and night sweat and called the ambulance. Donald is a known case of congestive heart failure and type II diabetes mellitus. He was recently discharged from the hospital (less than a week ago) on a 14 day course of intravenous Flucloxacillin 8g/24 hours via an elastomeric device secondary to a serious skin and soft tissue infection. His regular medications are: Novomix 30 Flexpen 32 units AM, 40 unit PM, Bisoprolol 10mg daily, Frusemide 40mg mane and 80mg middi, Lisinopril 20mg mane and Metformin XR 1g nocte.

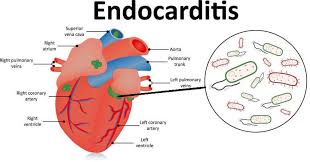

On presentation to ED, his physical examination revealed an audible heart murmur, petechiae, subungual (splinter) haemorrhages and osler nodes. His blood pressure and heart rate is normal. His temperature was 39.5 degrees Celsius and he appeared distressed with a normal respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute. He was also complaining of joint pain around left knee and ankle. The admitting doctor at the ED ordered an echocardiogram, draw two sets of blood cultures and send routine blood tests before referring him to internal medicine.

You noticed a raised WCC, increased CRP and the Gram-stain showing from the blood culture showing Gram-positive cocci in one of the two samples. You also noticed the echo report showing a mass near the mitral valve resembling a vegetation.

Various types of infective endocarditis

Right-sided IE [1]

- accounts for 10% of IE cases

- occurs most frequently in injection drug abusers

- younger patients with fewer comorbidities and less underlying valve disease versus left-sided IE

- 70% of these cases are because of S.aureus

- Signs and symptoms of septic pulmonary emboli (>50% have consistent chest radiograph showing this); pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea and hemoptysis

- Mortality rate <10%

Left-sided IE (LSIE) [2]

- Neurological complications appear in 20-40% of LSIE

- Best prevention is appropriate expedited antibiotic therapy initiation once IE is suspected (after blood cultures are obtained)

- Surgery is recommended if patient has indication for surgery and no prohibitive surgical risk

- High mortality (up to 50%)

Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis (PVE) [1]

- Risk = 1-5% within first year post-implantation and decreases about 1% per year thereafter

- Similar risks among mechanical and bioprosthetic valves; early IE risk is higher and late IE risk lower with mechanical valves

- Mortality is predicted by heart failure, S.aureus and presence of fistula or intacardiac abscess

- Comparable risks between aortic and mitral valves

- PVE within first 12 months post-surgery is mostly from coagulase-negative staphylococci or S.aureus whereas late-onset PVE has similar microbiology to NVE (native valve endocarditis)

- Surgical therapy often indicated and occurs in about 50% of PVE cases

- Medication therapy are similar in PVE and NVE with substantial differences in staphylococcal PVE

- For oxacillin-susceptible staphylococci strains; naficillin or oxacillin for at least 6 weeks duration, add rifampin for 6 weeks and low dose gentamicin for 2 weeks

Cardiovascular Device-Related IE [1]

- Most infections of pacemakers and ICDs occur only at the pocket

- 10% of pacemaker-associated infections include IE

- Best diagnosed with TEE

Here are specific organisms that cause IE [1]:

- Staphyloccus aureus (Gram-positive)

- Coagulase-negative staphylococci (causes very little acute IE, second most common PVE cause after S.aureus)

- Streptococci (Gram-positive); causes 30% of all IE and is less likely to cause acute IE

- Enterococci (Gram-positive)

- Gram-negative Bacilli

Diagnosis:

A definitive diagnosis of IE as per modified Duke’s criteria needs the presence of two major criteria or one major criteria and three minor criteria, or five minor criteria, or micro-organisms confirmed by culture or histology of vegetation , embolised vegetation, intracardiac abscess or histological evidence of active endocarditis (revealed by vegetation or intracardiac abscess). [3] Structural heart disease is a risk factor for IE since it causes turbulent blood flow. [1] The most common predisposing lesions include aortic valve disease, mitral regurgitation and congenital heart disease. [1] Other IE risk factors are prosthetic valves, prior IE episodes, invasive medical procedures, injection drug use, diabetes mellitus and kidney disease. [1]

Donald has met one major criteria and five minor criteria that confirm IE [3]:

- Vegetation or large intracardiac mass from positive echo report (Major criteria) [3]

- Predisposing heart condition (CHF)[3]

- Fever of at least 38 degrees Celsius [3]

- Immunological phenomena (Osler nodes) [3]

- Vascular phenomena (subungual splinter haemorrhages) [3]

- Microbiological proof of positive blood culture not meeting major criteria but excluding single positive culture for coagulase negative Staphylococci and organisms that do not cause endocarditis or serological proof of active infection with organisms that cause IE (Gram-positive cocci ; Staphylococcus aureus/Streptococci/Enterococci) [3]

Endocarditis is indicated by presence of Osler’s nodes, splinter haemorrhages, petechiae which are present in Donald. [4] Other endocarditis signs include Janeway’s lesions and clubbing (in longstanding disease). [3] Presence of his new heart murmur is significant of IE. [3,4] His muscle pain/arthralgia also confims IE. [4] Increased WCC and CRP and temperature>38.2 degrees Celsius confirms an infection. [5] Acute confusion is common in IE. [4] IE is suspected if fever is linked with known valvular or congenital heart disease (CHF), recent intervention of bacteremia (skin and soft tissue infection), evidence of CHF, vascular or immunological signs (splinter haemorrhages and osler nodes) and focal or non-specific neurological symptoms (confusion) and presence of new regurgitant heart murmur. [3]

Enterococci are the third leading cause of IE following staphylocci and streptococci. [1] Enterococci IE often occurs in older men with many comorbidities like Mr Trump, occurs disproportionately on the aortic valve and less commonly linked with embolic events compared to those caused by other organisms. [1] In this case, the mitral valve rather than the aortic valve is involved however. More definitive diagnostic tests are required to confirm offending pathogen.

Although Donald is an injection user (insulin), it is not intravenous drug use since insulin is subcutaneous. However he has received intravenous flucloxacillin through an elastomeric device. Despite this intravenous drug use, it is not abuse and an elastomeric pump decreases infection risks and his data and age group do not support Right-sided IE. Furthermore, the involvement of vegetation on the mitral valve leans towards Left-sided IE. IE based on a large observational cohort study is most commonly involved with the mitral valve (40%) like in this case. [1] Donald has no prosthetic valves and based on above, he has acute left-sided (mitral valve) native valve endocarditis (NVE) and should be treated accordingly. [1]

Importance of blood cultures in diagnosis

Appropriate diagnosis is important to direct correct treatment. Thus at least three blood cultures should be drawn when IE is suspected (first and last drawn at a minimum of one hour apart, preferably from different sites). [1] Other diagnostic criteria include history and physical exam. Donald has presented with acute IE with the abrupt onset of fever. [1]

Blood cultures are the most important tests because it’s vital to determine the offending micro-organism/(s) so as to direct appropriate medical treatment and provide useful prognostic information. [6] Electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, urinalysis and rheumatoid factor can assist in diagnostics and finding the complications of IE. [1] Blood and valve cultures are gold-standard for detecting IE-causing organisms but unfortunately, these tests only detect culturable pathogens and have low sensitivity especially in those previously treated with antibiotics like Donald. [7,8]

According to the modified Duke Criteria for IE diagnosis, it requires persistent positive blood culture results; 2 positives drawn 12 hours apart or all of 3 or majority of 4 positive blood culture results with the first and last drawn >1 hour apart. [1]

Unfortunately, Donald’s blood culture results only show 1 out of 2 positive which does not support Duke’s major criteria diagnostics to confirm IE organism responsible. [1] The reason behind these negative results is highly likely because of antibiotic use of flucloxacillin prior to blood-sample withdrawal. [6] Flucloxacillin treats Staphylococcal infections and is empirical treatment for endocarditis according to AMH.

Blood cultures must also be drawn 24-48 hours after antibiotics treatment initiation until they are negative. [1] Duration of treatment is counted from the time on the first negative blood cultures and usually requires continuation for six weeks after blood culture results are negative. [1]

Antibiotic choice

Presence of vegetation structure sequesters bacteria from the bloodstream thus requiring long durations of therapy. [1] Parenteral antibiotics are preferred over oral as we need a sustained and reliable antibiotic blood levels. [1]

Mr Smith has had one positive blood culture for Gram-positive cocci which narrows it down to Staphyloccus, Streptococci or Entrococci. [1] The history of serious skin and soft tissue infection when discharged from hospital treated by flucloxacillin indicates he was being treated for a Staphylococcal infection. High in-hospital and 1-year mortality IE is most commonly caused by viridians streptococci. [6] Staphylococcal aureus is the causative agent in 50% of all IE cases and is the leading cause of acute IE and tends to involve the mitral valve more frequently than the aortic (like in this case). [1,6] S.aureus is known for malignant IE course and often requires early surgery for successful eradication. [6] The presence of fever and raised WCC and CRP indicate that there is still active infection not adequately managed by β-lactamase resistant antibiotic flucloxacillin which may suggest the presence of other offending organisms.

Enterococci are the third leading cause of IE following staphylocci and streptococci. [1] Enterococci IE often occurs in older men with many comorbidities like Mr Trump, occurs disproportionately on the aortic valve and less commonly linked with embolic events compared to those caused by other organisms. [1]

Mr Smith has factors linked with poor prognosis like left-sided IE, heart failure, large vegetation mass and immunocompromised status due to his diabetes. [1] Thus, he will need longer duration of antibiotic therapy and parenteral form is preferred. [1]

TREATMENT

Treating blood-culture negative endocarditis (BCNE) depends on the likely or causative pathogen if known. [9] Antibiotic therapy must be instituted as soon as possible to minimize valvular damage.

BCNE Empiric treatment is IV benzylpenicillin (Penicillin G), flucloxacillin and gentamicin for NVE in this case. [9] In those with prosthetic heart valves or intracardiac devices, vancomycin and gentamicin are the recommended empiric choice plus cefepime or an antipseudomonal carbepenem. [9] Directed therapy is dependent upon causative BCNE organism. [9]

For NVE, empiric treatment is mostly vancomycin. [10]

Definitive diagnosis will direct appropriate treatment and many laboratories in Australia can use pan-bacterial PCR assay to get an amplified 16SrRNA region of the bacteria to obtain the offending organism though valve analysis. [9,11] Though this method is not without limitations, it is useful where there’s high suspicion of a particular cause of BCNE (blood-culture negative endocarditis) with positive or ambiguous serological test results like in this case. [9] Furthermore, molecular detection methods are also beneficial in patients who’ve received antibiotics like Mr Smith which caused bacterial DNA levels to persist at levels below that detectable by culture. [9] I would recommend more blood tests and laboratory tests to confirm definitive diagnosis.

His treatment options for NVE are as follows:

Due to the presence of Gram-positive cocci, penicillins G (benzylpenicillin) and V (phenoxymethylpenicillin) being highly active against these organisms should be used for treatment. [3] However both of these are β-lactamase labile. First generation Cephalosporins can be used due to their excellent Gram-positive and modest Gram-negative activity. [3]

Staphylococcal aureus [1,3];

- Cloxacillin or nafcillin/oxacillin 2g IV q4hfor 4-6 weeks with or without gentamicin 1mg/kg IV/IM q8h for 3-5 days versus vancomycin 15mg/kg IV q12h for 4-6 weeks with gentamicin for 3-5 days or cloxacillin or oxacillin for 4-6 weeks with 3-5 days gentamicin and rifampin for 6 weeks or vancomycin for 4-6 weeks with 3-4 days gentamicin and rifampin for 6 weeks

For Streptococcus [3];

- Penicillin (amoxycillin or ampicillin or penicillin G) or ceftriaxone for 4 weeks or, Penicillin (amoxycillin or ampicillin or Penicillin G) or ceftriaxone with gentamicin or netilmicin for two weeks or vancomycin for 4 weeks with gentamicin for 2 weeks

For Enterococcus [1];

- Enterococcus spp. Susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, gentamicin and vancomycin are treated with Ampicillin 2g IV q4h (4-6 weeks) plus gentamicin 1mg/kg IV/IM q8h (4-6 weeks) OR penicillin G 18-30 million U IV per 24 h (4-6 weeks) plus gentamicin 1mg/kg IV/IM q8h (4-6 weeks). [1]

- In penicillin/ampicillin allergy, modify above to vancomycin 15mg/kg IV q12h for 6 weeks plus gentamicin 1mg/kg IV/IM q8h for 6 weeks. If β-lactamase production is evident, ampicillin-sulbactam 3g IV q6h plus gentamicin 1mg/lg IV/IM q8h for 6 weeks. [1]

Based upon limited definitive data of offending organism, a potential antibiotic regimen that targets all the above three above organism could be [1,3, 9,10]:

- Vancomycin 15mg/kg IV q12hfor 6 weeks plus gentamicin 1mg/kg IV q8h for 6 weeks

- Where vancomycin or an aminoglycoside is used, we need to monitor drug levels to ensure adequate dosing and prevent toxicity because gentamicin and vancomycin both increase nephotoxicity and ototoxicity. [1]

- Antibiotic treatment should continue for 6 weeks after blood culture results become negative. [10]

However due to the toxicities and resistance linked with vancomycin and aminoglycosides, the use of prolonged gentamicin (>3-5 days) is linked with increased toxicity and we want to minimise toxicity where possible. Furthermore, the Swedish Reference group for antibiotics (SRGA) suggested using aminoglycosides in combination with β-lactam antibiotics in endocarditis to be limited to resistant cases where β-lactam monotherapy is insufficient or the organism is non-resistant to aminoglycosides. [12] Data is conflicting as far as the safety and efficacy of prolonged aminoglycosides in endocarditis for up to 4-6 weeks. [12,13] Research have also reported that ceftriaxone could be a safer equipotent alternative to gentamicin in certain endocarditis types. [13]

Risk factors for developing fungal endocarditis include immunosuppression, parenteral nutrition (from previous hospitalization), broad-spectrum antibiotic regimens and cardiovascular surgery and peripheral emboli and large vegetations are commonly found. [11] There is high mortality and antifungal therapy with surgery is a choice treatment. [11] We need to watch for epidemiological clues, serologi and molecular techniques and blood cultures to identify other potential IE organisms like Legionella, Mycoplasms, Chlamydia, Mycobacteriia and viruses. [14]

β-lactam antibacterial effects are time-dependent (related to time in which free unbound drug concentration is maintained above the minimum inhibitory concentration; fT>MIC). [15] Maximising fT>MIC increases therapeutic effectiveness and minimizes drug resistance risk and bactericidal activity at infection site is necessary for cure. [15] fT>MIC of 100% in plasma is reported to have microbiological and clinical cures by retrospective analysis of clinical data. And p-concentrations of four to fivefold the MIC throughout dosing interval, is vital for maximal bactericidal effects in critically ill people. [15]

Conclusion of Treatment Choice for Donald: According to the information we have so far and mitral valve involvement, the most likely suspected organism could be Staphylococcal aureus and treatment for methicillin susceptible strains of S.aureus (MSSA) involves naficillin/oxacillin (β-lactam antibiotics that’s β-lactamase resistant) 2g IV for 4-6 weeks and gentamicin can be added for 3-5 days at 3mg/kg/day in 2 or 3 divided doses if needed. [1,3] In MRSA-IE, vancomycin monotherapy for 6 weeks with target vancomycin troughs of 10-16mcg/dL is the treatment choice. [1]

The Danish endocarditis treatment guidelines recommend Penicillin-G as a treatment of choice for IE from streptococci and penicillin-susceptible staphylococci. [15] It can also be used to treat penicillin-susceptible enterococci at MIC≤8mg/L as a substitute to ampicillin and gentamicin which are the first-line recommended treatment. [15] Hence, Penicillin-G could be a treatment option instead of naficillin/oxacillin so as to target all three possible IE organisms. [15]

Empiric antibiotic treatment depends on the most likely infecting organisms and is guided by clinical history and physical examination data. [17] Three to five blood cultures should be obtained within 60-90 minutes or over a few hours followed by correct antibiotic regimen infusion. [17]Brusch et al. reported that NVE has frequently been treated with Penicillin-G and gentamicin for synergistic streptococci coverage whereas those with intravenous-drug use history are treated with naficillin and gentamicin for methicillin-sensitive staphylococci. [17] MRSA and penicillin-resistant streptococci changes this empiric treatment to substitute vancomycin instead of penicillins. [16]

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is an important tool to guide antibiotic therapy especially in critically ill people. [15] TDM and subsequent dose-adjustments according to patient’s pharmacokinetic changes are vital to provide an individualised approach to antimicrobial treatment. [15] Penicillin-G plasma concentrations varies greatly in IE patients because they are affected by age, weight, eCLcr and p-albumin. [15] In IE from streptococci and penicillin-susceptible staphylococci, Penicillin G 3 g q6h causes therapeutic concentrations above PK/PD targets commonly used. [15] In enterococci IE however, Peniciilin G should only be chosen if TDM is available to optimize Penicillin G exposure and to assess if an alternative dosing regimen is required. [15]

The main goals of IE therapy are to eradicate the infectious organism from the thrombus and address valvular infection complications which includes intracardiac and extracardiac IE consequences. [16] Correct diagnosis is imperative.

Eradicating bacteria from fibrin-platelet thrombus is very challenging due to the high concentration of organisms within the large vegetation (100-100 billion bacteria per gram of tissue), their location deep inside the thrombus, their position at both a reduced metabolic and reproductive state and interference from fibrin and white blood cells with antibiotic action. [16] Thus intravenous bactericidal antibiotics are required. [16]

We need to stabilize Mr Smith due to his cardiac instability and these measures should be followed [16]:

- Treat CHF

- Oxygen

- Hemodialysis (may be needed in renal failure)

Assuming empiric treatment used in Mr Smith was Penicillin-G (β-lactamase labile antibiotic) 3g q3h, hypotension, fever, chills and headache may be due to Jarisch-Herxheimer recation to Penicillin-G. [17] Symptoms can be managed with aspirin or prednisolone. [18] Other causes of deterioration could be attributed to wrong suspected organism and treatment regimen should be altered accordingly.

Most likely source of infection is Enterococcus spp;

Enterococcus faecalis may become resistant to penicillins because they produce β-lactamases and Peniciillin-G is not β-lactamase resistant. [16] These can be treated with ampicillin with sulfabactam or vancomycin combined with gentamicin. [16] Synergistic bactericidal activity from gentamicin does not need high peak levels. [16] Peak gentamicin levels of 3-5mcg/mL with a trough<2mcg/mL can be achieved with gentamicin dose of 1mg/kg IV every 8 hours. [16] Avoid once daily gentamicin dosing because a prolonged postantibiotic effect against Gram-positive organisms does not happen and synergistic effect requires simultaneous presence of active in the call wall and an aminoglycoside. [16] Although overall mortality is not increased with gentamicin use for synergistic effects, it is still linked with reduced renal function so care must be exercised to achieve synergy against enterococci with continued use but TDM is vital for patient’s overall wellbeing.

Conclusion of Changing Mr Smith’s New Antibiotic regimen are as follows;

*As guided by The American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines [16]:

- Non-resistant enterococci, resistant S viridans (MICs of penicillin G of >0.5 mcg/mL), or nutritionally variant S viridans and PVE caused by penicillin-G–susceptible S viridans or S bovis are treated as follows:

- Penicillin-G at 18-30 million U/d IV, either by continuous pump or in 6 equally divided doses daily, combined with gentamicin at 1 mg/kg (based on ideal body weight) IM or IV every 8 hours for 4-6 weeks, or

- Recommended preferred option for Mr Smith: Administer ampicillin at 12 g/d by continuous infusion or in 6 equally divided doses daily, combined with gentamicin at 1 mg/kg (based on ideal body weight) IM or IV every 8 hours for 4-6 weeks (considering Donald had problems Penicillin-G from Jarisch-Herxhemer reaction or other causes)

If Mr Smith is allergic to penicillin, give vancomycin at 30 mg/kg/d in 2 equally divided doses (don’t exceed 2 g/24 h unless serum levels are monitored). [16] This may be combined with gentamicin for 4-6 weeks of treatment. [16] A peak vancomycin level of 30-45 mcg/mL should be achieved 1 hour post-completion of the intravenous infusion. [16]

*Antibiotic regimen options for Donald For Enterococcus [1];

- Enterococcus spp. Susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin, gentamicin and vancomycin are treated with Ampicillin 2g IV q4h (4-6 weeks) plus gentamicin 1mg/kg IV/IM q8h (4-6 weeks) OR penicillin G 18-30 million U IV per 24 h (4-6 weeks) plus gentamicin 1mg/kg IV/IM q8h (4-6 weeks). [1]

- In penicillin/ampicillin allergy, modify above to vancomycin 15mg/kg IV q12h for 6 weeks plus gentamicin 1mg/kg IV/IM q8h for 6 weeks. If β-lactamase production is evident, ampicillin-sulbactam 3g IV q6h plus gentamicin 1mg/lg IV/IM q8h for 6 weeks. [1]

Enterococcal PVE generally responds similar to disease involving native valves. [16] Six weeks of treatment is recommended for those with symptoms of enterococcal IE of >3 months’ duration, with relapsed infection, or with PVE.[16]

Combining an inhibitor of cell-wall synthesis (ie, penicillin, vancomycin) with an aminoglycoside (ie, gentamicin, streptomycin) is necessary to achieve bactericidal activity against enterococci. [16]

There is consistent in-vitro and in-vivo laboratory results proving the synergy between vancomycin or daptomycin and an anti-staphylococcal β-lactam antibiotic as well as increasing clinical data to support these combinations to improve outcomes from MRSA such as a recent pilot randomised controlled trial CAMERA-2 which reported a reduction in bacteremia duration from using vancomycin and flucloxacillin combined versus vancomycin monotherapy. [18] The benefits of adding anti-staphylococcal β-lactams to standard MRSA therapy are safety, wide availability and low cost.[2] Furthermore, vancomycin showed slower bactericidal activity poorer tissue penetration and slower bacteremia clearance compared to anti-staphylococcal β-lactams (oxacillin and its derivatives flucloxacillin, cloxacillin and nafcillin).[18]

In a single-centre retrospective cohort study (50 patients with MRSA-B), Dilworth and colleagues reported a higher rate of microbiological eradication in the combination therapy group (vancomycin and at least 24 hours of β-lactam) versus vancomycin monotherapy (96% versus 80%, P=0.02). [18] CAMERA-1 (prospective clinical trial, open-label design) by Davis et al. included the randomisation of 60 patients to vancomycin or combined therapy (vancomycin and flucloxacillin) conducted in seven Australian centres reported mean bacteremia clearance of 2 versus 3 days with standard therapy (P=0.06). [18]

Increasing frequency of enterococci have aminoglycoside-inactivating enzymes that make them relatively resistant to the usual synergistic combinations. [17] These aminoglycoside-resistant strains have an MIC of 2000 mcg/mL or more for streptomycin and 500 mcg/mL or more for gentamicin. [16] Of gentamicin-resistant enterococcal strains, 25% are susceptible to streptomycin.[17] Hence, depending on patient’s response to therapy, we can adjust regime if necessary.

Continuously infused ampicillin (serum level of 16 mcg/mL) is considered the best therapy for aminoglycoside-resistant enterococci.[17] Alternatives include imipenem, ciprofloxacin, or ampicillin with sulbactam. [16] Vancomycin doesn’t appear to be as useful as the previous antibiotics mentioned with the emergence of Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis (VRE), which cause the most challenging nosocomial infections which currently have no highly effective proven therapy for IE from VRE strains. [16]

BCNE in those who’ve received previous antibiotics are normally treated with vancomycin and gentamicin and initial treatment include vancomycin plus gentamicin and ciprofloxacin (preferred regime due to increase renal failure risk) or ampicillin-sulfa-bactam plus gentamicin (3mg/kg/day). [16]

A prospective study of BCNE by Menu et al. used four intravenous antibacterials; amoxycillin, vancomycin, gentamicin and amphotericin B and reported efficacy and low mortality rates from this protocol (using amoxycillin instead of ampicillin and genatmicin in community-acquired IE and vancomycin combined with gentamicin for maximal coveralge of the most common prganisms in healthcare-associated IE) which is similar to the European empiric treatment guidelines which recommend the first-line drug choices to be ampicillin/flucloxacillin and cloxacillin or oxacillin used in combination with aminoglycoside if site of intection is a native valkve or a prosthetic valve,1 year old. [18] In allergic cases, vancomycin and gentamicin are considered most appropriate. [18] Werner et al. (10 year BCNE survey) reported aminoglycoside therapy was vital for survival in BCNE. [18]

Preventative measures to prevent recurrence:

Since Mr Smith has significant CHF, administer a sodium-restricted diet and limit his activity. [16] Appropriate antibiotic therapy is essential.

Patients with CHF like Mr Smith should be considered for surgery due to decreased penetration of antibiotics to the site of infection and the possible risk of the abscess causing heart block acute valvular dysfunction. [1] Those at high embolism risk should also be considered for surgery. [1] Moreover, neurological complications (confusion) increase mortality by 50%, makes clinical management difficult and usually their presence indicates need for surgery. [2] Presence of large vegetation mass and congestive heart failure or cardiac insufficiency also indicate surgery and retrospective studies have reported that medical management alone is linked with higher mortality than combined surgical and medical management. [1,6] Management will require intravenous antibiotics and considering early surgery for removal of infective tissue and valve replacement in those with poor prognosis or complications like Donald. [6]

Valve-replacement surgery should be promptly done if any of the below occurs [16]:

- Valve dysfunction (as revealed by cardiac effects like tachycardia, tachypnea etc)

- Moderate-to-severe CHF

- Perivalcular or myocardial abscess formation

- Presence of unstable valve that is detaching from the valve ring

- >1 embolic episode with persistent vegetations (as per transtracheal echocardiogram)

- Presence of vegetations >1cm in diameter

Mild CHF from valvular insufficiency can be managed with standard medical threatment. [17] However, this can be progressive and despite obtaining microbiological cure, it may require valvular surgery. [16]

If valve-replacement surgery is warranted for Donald, we need to consider the high prevalence of fungi in nosocomial post-surgical BCNE (<1 year) and add amphotericin B antifungal treatment if fever persists 48 hours post-antibiotic empiric treatment. [19]

Definitive diagnosis is pertinent is directing optimal appropriate therapy and a PubMed, Embase and Cochrane database systematic review were conducted on diagnostic methods and their performance. [20] They reported consistently positive evidence of the benefit of using F-FDG PET/CT (F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT) and MDCTA(multidetector CT angiography) for non-invasive diagnostics of NVE, intracardiac prosthetic-material-related infection and extracadiac foci in adults and concluded the benefits of using additional imaging techniques if IE is suspected. [20,21] Valve histopathology has high sensitivity in IE diagnosis compared to valve culture and blood cultures are the mainstay in IE diagnosis but limitations have been seen from low sensitivity from high rates of BCNE and prior antibiotic use. [22]

Because of the many organisms implicated in IE, a case report by Rapsinski et al. reported that there’s a rare bacterial IE cause secondary to P.mendocina pathogen with all native valves being affected and a majority of them were left-sided like in Donald’s case which stresses the importance of correct diagnosis. [23] In P.mendocina infections, they recommended third-generation cephalosporins as first-line treatment instead of ampicillin, ampicillin/sulfabactam or first and second generation cephalosporins despite susceptibility. [23] Guidance from antimicrobial susceptibility prodiles as per CSLI standards are useful in providing optimal therapy with favourable clinical results even though staphylococci have replaced streptococci as the most commonly associated pathogen linked with health-care contact and invasive procedures. [23,24] Streptococcus Agalactiae which is fatal have also been implicated in mitral valve IE thus clinicians should be aware of possible perivalvular extension of infection which can lead to heart block. [25]

Surgery, increased age and indwelling cardiac devices increase IE prevalence and 1 year-mortality of IE has not improved and remains at 30%. [24] More randomised trials are necessary for better clinical management and address the many controversies like antibiotic prophylaxis in IE. [24] Increased use of long-term intravenous lines, invasive procedures, prosthethic valces and indwelling cardiac devices have led ti upsurge of staphylocoocal bacteremia and health-care acquired IE is responsible for 25-30% of the cohorts in high-income countries. [24] A multi-modality approach in needed to effectively manage IE and depends on strategies to minimise health-care associated bacteremia and more clarity on the controversial issue of antibiotic prophylaxis are needed along with more insight and research into infection-resistant materials for prosthetic valves and cardiac devices. [24] Integration of multidisciplinary healthcare IE teams, multimodality imaging and microbiological services will allow for earlier decision-making and interventions to optimize patient care. [24]

Gentamicin toxicity:

Due to the change in Mr Smith’s regimen to include gentamicin, we need to consider the associated nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. Despite cohort studies reporting that overall risks are linked with cumulative dose, ototoxicity can happen at low doses and are often irreversible. [26] More evidence is needed to support non-aminoglycoside-based regimens in IE, use of shortened courses and single daily doses of gentamicin. [26] Since gentamicin use is unavoidable in this case, informed consent, close renal function monitoring and advising Donald to be alert of ototoxicity symptoms (hearing impairment, tinnitus, loss of balance, oscillopsia) are vital in care. [26]

Other Preventative strategies in IE [27,28]:

- Reduce hospital-acquired bacteremia [27]

- Good oral hygiene for high risk groups like Donald [27]

- Antibiotic prophylaxis for high risk people (before selected dental and invasive surgical and diagnostic procedures) [27,28]

- Antibacterial coating/materials [27]

Surgery implications:

A meta-analysis by Mihos et al. evidenced a lower 30-day mortality and higher survival at follow-up for PVE patients who underwent valve reoperations compared to medical treatment although prospective studies are needed to confirm this and guide clinical-decisions in regards to specific patient groups who would benefit from a valve reoperation versus medical therapy alone. [29]

Surgery is still the primary IE treatment though it is unclear which prosthetic valve gives better prognosis. [30] A meta-analysis comparing IE prognosis of using biological valves versus mechanical valves was conducted through Pubmed, Embase and Cochrane databases and reported that mechanical valves offer significantly better prognosis in IE. [30] A large multicenter retrospective study confirms this though retrospective studies have their limitations. [28] Prospective studies (higher evidence level) reveal inconsistent results which necessitate further randomized studies to verify this benefit. [30]

Early surgery compared to conventional medical therapy has been suggested to reduce in-hospital, follow-up and IE mortality confirmed by current limited evidence (retrospective studies) because it resulted in better cardiac function, lower embolic events and decreased mortality. [31] Treatment is aimed at preventing recurrence and with the development of antimicrobials and improvements in pathogen investigations through PCR technique amongst others, early surgery hasn’t been proven to elevate reinfection rates and hence long-term antimicrobial therapy duration is unnecessary. [31]

IE after Mitraclip procedure presents a dilemma because of IE recurrence. [32] Although surgery is a favourable treatment modality, patients in the analysis of case reports by Boeder et al were rejected due to high operative risk and the leading cause of IE recurrence is a bacterial infection by staphylococcal bacteria. [32] Therefore, optimal treatment recommendations should be individualised based on each patient’s factors.

After surgery-care:

Patients like Mr Smith who had adequate control of enterococcal IE through surgery would have less treatment efficacy with a cell wall-active antibiotic monotherapy versus combination antimicrobial that included an aminoglycoside as adjunct post-surgery as evidenced by a retrospective cohort study of only surgically treated patients which is this study’s major strength (Banson et al). [33]

The persistent high mortality associated with IE is attributed to high frequency of poly-microbial infections, pathogenic diversity and intracellular persistence of common IE-causing organisms. [34] Improved bacterial diagnosis through 16S rDNA NGS helps increase individualisation of antibiotic treatment for better outcomes. [34]

It’s important to consider current controversies in IE; prevention of IE (antibiotic prophylaxis and ways to minimize healthcare-associated bacteremia), multimodality-imaging as diagnostic-basis and optimal timing of surgical-intervention and the challenges of increasing rates of cardiac device infection. [35,36]

REFLECTIVE SUMMARY OF MY LEARNING FROM THIS TASK (Max: 500 words)

I have learned that there are many organisms that can cause IE. From researching, I found that there exists much controversy within IE in regards to prevention, diagnostics and optimal timing of surgical intervention which necessitates further investigations through RCTs despite logistical challenges or high-quality case-control studies. There exist inherent risks with antimicrobial use especially in matters of resistance and aminoglycoside-related toxicity which can limit certain treatment regimens. The main points that I have learnt were the importance of individualized treatment regimes (antibiotic/surgical or both) which are guided by offending pathogens, location of infection, patient’s age, comorbidities, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors as well as patient groups of whether they are classified as high-risk.

A landmark RCT comparing early surgery (within 48 hours) with conventional treatment in stable patients with NVE, echocardiographically severe valvular regurgitation and large vegetations, reported a significant reduction of in-hospital death or embolism in younger patients (mean age= 47 years old) but these benefits do not translate to older and frailer IE patients and in PVE, retrospective studies investigating early surgery do not support a benefit. [34]

Surgery should only be considered for those in highest-risk groups like Mr Smith as follows despite being performed in 40-50% of IE patients [34]:

- Very large vegetations (>30mm)

- Perisistent large vegetations (>10mm) after embolic event despite antimicrobials

- Mobile vegetations

- Staphylococcal infection

- Mitral valve location

It led me to reflect on the prevalence and risks of the different types of IE which have high mortality regardless of different countries (based upon industrialization/modern versus poorer countries; the varied organisms involved) and the challenges associated with the successful clinical management of IE due to issues of resistance, risks associated with antimicrobials and surgery, increasing patient age and the objective of preventing recurrence which can be catastrophic.

This brings me onto the strategies of prevention, diagnostic improvement and optimal management of IE as previously discussed. Optimal management of patients should thus require endocarditis team evaluation, customized antibiotic treatment, early risk-examination and expedited transfer to expertise departments, early surgery for high-risk patients and the importance of TDM and overall monitoring. A multidisciplinary multi-factorial approach is recommended to ensure optimal patient care and management of IE.

I have also learnt that there are risks of recurrent IE infections from bacteria as well as fungi after surgery and there should be strategies to manage these accordingly.

Pharmacists play a vital role in recommending appropriate antibiotic therapy and are well-placed to assist in TDM and proper counselling and communication to patients of inherent risks associated with each treatment option.

REFERENCES

1) McDonald JR. Acute infective endocarditis. Infect Dis Clin North Am.2009 Sept;23(3):643-664

2) San-Roman JA, Vilacosta I, Lopez J and Sarria C. Critical questions about left-sided infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol.[Internet]. 2015 Sept; 66(9). Available from: http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/669/1068

3) Marti-Carvajal AJ, Dayer M, Conterno LO, Gonzalz-Garay AG, Mrti-Amarista CE and Simancas-Racines D. A comparison of different antibiotic regimens for the treatment of infective endocarditis. Cochrane Heart Gp. [Intrenet]. 2016 Apr 19. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009880.pub2/full

4) Ashley EA, Niebauer J. Infective endocarditis. London Remedica. [Internet]. 2004;Cahpter 10. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2208/

5) Povoa P, Coelho L, Almedida E, Fernandes R, Mealha R, Moreira P and Sabino H. C-reactive protein as marker of infection in critically ill patients. Clin Microbiol and Infect. [Internet] 2005;11(2): 101-108. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1198743X14622072

6) Hitzeroth J, Beckett N and Ntuli P. An approach to patient with infective endocarditis. S Afr Med J. [Internet]. 2016 Feb;106(2): 145-50. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/27303769

7) Fukui Y, Aoki K, Okuma S, Sato T , Ishil Y and Tateda K. Metagennomic analysis for detecting pathogens in culture-negative infective endocarditis. J Infect Chemother. [Internet]. 2015 Dec;21(12):882-4. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/26360016

8) Tattevin P, Watt G, Revest M, Arvieux C and Fournier PE. Update on blood culture-negative endocarditis. Med Mal Infect. [Internet]. 2015 Jan-Feb;45(1-2):1-8. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/25480453

9) Subedi S, Jennings Z and Chen SCA. Laboratory approach to the diagnosis of Culture-negative infective endocarditis. Heart Lung Circ. [Internet].2017 Aug;26(8):763-771. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/science/article/pii/S1443950617300975?via%3Dihub

10) Khan ZA and Hollenberg SM. Valvular heart disease in adults: infective endocarditis. FP Essent.[Internet]. 2017 Jun;457:30-38. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/28671807

11) Peeters B, Herjigers P, Beuselink K, Vernhagen J, Peetermans WE, Herregods MC et al. Added diagnostic value and impact on antimicrobial therapy of 16S rRNA PCR and amplicaon sequencing on resected heart valves in infective endocarditis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol and Infect. [Internet].2017 Jun 19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2017.06.008

12) Hanberger H, Edlund C, Furebring M, G. Giske C, Melhus Å, Nilsson LE, et al. Rational use of aminoglycosides—Review and recommendations by the Swedish Reference Group for Antibiotics (SRGA). Scand J Infect Dis 2013;45:161–75. doi:10.3109/00365548.2012.747694.

13) Jackson J, Chen C, Buising K. Aminoglycosides: how should we use them in the 21st century? Curr Opin Infect Dis 2013;26:516–25. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000012.

14) Houpikian P, Raoult D. Blood culture-negative endocarditis in a reference center: etiologic diagnosis of 348 cases. Medicine. 2005 May; 84(3):162-173

15) Obrink-Hansen K, Wiggers H, Bibby BM, Jensen K, Thomsen MK, Brock B and Petersen E. Penicillin G treatment in infective endocarditis.\ patients-does standard dosing result in therapeutic plasma concentrations? Basic Clin Pharmacol & Toxicol. [Internet]. 2017 Feb;120(2): 179-186. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/doi/10.1111/bcpt.12661/full

16) Brusch JL. Infective endocarditis treatment and management. Medcape. [Internet]. 2017 Aug 9. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/216650-treatment#d8

17) Forestier E, Fraisse T, Roubaud-Baudron C, Selton-Suty S and Pagani L. Managing infective endocarditis in the elderly:new issues for an old disease. Clin Interv Aging. [Internet]. 2016;11:1199-1206. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pmc/articles/PMC5015881/

18) Tong SY, Nelson J, Paterson DL, Fowler VG, Howden BP, Cheng AC et al. CAMERA2-combination antibiotic therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. [Internet].2016 Mar ;17:170. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pmc/articles/PMC4815121/

19) Menu E, Gouriet F, Casalta JP, Tissot-Dupont H, Vecten M, Saby L et al.Evaluation of empirical treatemtn of blood culture-negative endocarditis. J Antimicrob Chemother. [Internet]. 2017 Jan;72(1):290-298. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/27678286

20) Gomes A, Glaudemans AW, Touw DJ, Can-Melle JP, Willems TP, Maas AH et al. Diagnostic value of imaging in infective endocarditis: a systematic reviewe. Lancet Infect Dis. [Internet].2017 Jan;17(1):e1-e14. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/27746163

21) Rapsinkski GJ, Makadia J , Bhanot N and Min Z. Pseudomonas native valve endocarditis: a case report. J Med Case Rep.[Internet]. 2016 Oct 4;10(1): 275. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/27716406

22) Granados U, Fuster D, Pericas JM, Llopsis JL, Ninot S, Quinana E. Diagnostic accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT in infective endocarditis and implantable cardiac electronic device infection: a corss-sectional study. J Nucl Med. [Inetenet]. 2016 Nov;57(11): 1726-1732. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/27261514

23) Brandao TJ, Januario-da-Silva CA, Correia MG, Zappa M, Abrantes JA, Dantas AM et al. Histopathology of valves in infective endocarditis, diagnostic criteria and treatment considerations. Infection. [Internet]. 2017 Apr;45(2):199-207. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/27771866

24) Labriola L, Jadoul M. Infective endocarditis. The Lancet. [Internet]. 2016 Mar 4; 387(10021):882-893. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/science/article/pii/S0140673615000677?via%3Dihub

25) Araj M, Nagashima K, Kato M, Akutsu N, Hayase N, Hayase M et al. Complete atrioventrcular block complicating mitral infective endocarditis caused by streptococcus agalactiae. Am J Case Rep. [Internet]. 2016;17: 650-654. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pmc/articles/PMC5017695/

26) Cahill TJ and Prendergast BD. Reply:Infective endocarditis, gentamicin and vestibular toxicity. J Am Cardiol. 2017 Jul;70(2): 298-299. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/science/article/pii/S0735109717373369?via%3Dihub

27) Cahill TJ, Baddour L, Habib G, Hoen B, Salaun E, Gosta B et al. Challenges in infective endocarditis. J Am Cardiol. 2017 Jan 24;69(3): 325-344. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/science/article/pii/S0735109716371121?via%3Dihub

28) Ba DM, Mboup MC, Zeba N, Dia K, Fall AN, Fall F et al. Infective endocarditis in Principal Hospital of Dakar: a retrospective study of 42 cases over 10 years. Pan Afr Med. [Internet]. 2017;26:40. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pmc/articles/PMC5398261/

29) Christos G, Mihos DO, Capulade R, Yucel E, Picard MH, Santana O et al. Surgical versus medical therapy for prosthetic valve endocarditis: a meta-analysis of 32 studies. The Ann Thor Surg.[Internet].2017 Mar;103(3):991-1004. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/science/article/pii/S0003497516313443?via%3Dihub

30) Tao E, Wan L, Wanj WJ, Luo YL, Zeng JF and Wu X. The prognosis of infective endocarditis treated with biological valves versus mechanical valves: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. [Internet]. 2017;12(4): e0174519

Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pmc/articles/PMC5390962/

31) Jia L,. Wang Z, Fu Qian, Biu Huaien and Wei M. Could early surgery get beneficial in adult patients with active native infective endocarditis? A meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int.[Internet]. 2017;2017:3459468. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pmc/articles/PMC5343223/

32) Boeder NF, Dorr O, Rixe J, Weiperrt K, Bauer T, Bayer M et al. Endocarditis after interventional repair of the mitral valve: review of a dilemma. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. [Internet]. 2017 Mar;18(2): 141-144. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/27890554

33) Banzon JM, Hussain ST, Gordon SM, Pettersson GB, Butler RS, Shrestha N. Aminoglycosides for surgically treated enterococcal endocarditis. Sem Thor Cardiovasc Surg. [Internet]. 2016;28(2): 331-338. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/science/article/pii/S1043067916300466?via%3Dihub

34) Oberbach A, Schlichting N, Feder S, Lehmann S, Kullnick Y, Buschmann T et al. New insights into valve-related intramural and intracellular bacterial diversity in infective endocarditis. PLoS One. [Internet]. 2017;12(4): e0175569. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pmc/articles/PMC5391965/

35) Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Current controversies in infective endocarditis. F100Res. [Internet]. 2015 Nov 18;4. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-ezproxy.utas.edu.au/pubmed/26918142

36) Cahill TJ, Harrison JL, Jewell P, Onakpoya I, Chambers JB, Dayer M et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for infective endocarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Valv Heart Dis.. [Internet]. 2017;103:937-944