Nursing Homes and Understanding a Good Day to Die

Lately I’ve been spending time in hospitals and nursing homes, visiting several people in the family (when it rains it pours). Rather suddenly I’ve been exposed to many impressions of late life, and – as a whole – we Americans are missing something important.

The family members I visited (spread over four facilities) needed some medical help, of course, but none were really bad off. No, not compared to the people in the next bed or the next rooms. When visiting there, walking down the hallways, you saw them, and although many were simply seniors with medical problems, others were . . . well, something else.

In the hallways, in wheelchairs, there were old people who had frail bodies but stronger minds, and they’d engage you in some level of conversation. I understood their being there. But with others – like the grandmother-aged woman who clutched a babydoll, smelled of urine, and looked at you with lonely, frightened eyes – there was something just not right about it all. Walking down the hallways, glancing into the rooms, I saw quite a few Dali-esque human-shaped blobs draped across beds and strapped upright into wheelchairs, most seeming to be drained of all but the very last spark of life.

I am in no way implying that as a society we should . . . push those barely-alive people down the stairs or out in front of a bus. I am NOT suggesting anything like that. But there’s something wrong about the big picture here.

The Purpose of Medicine

First of all, medicine should be used for two reasons only: to help someone heal and get better, or to alleviate pain. I don’t think we’re doing anybody any favors when we use medicine just to keep someone alive so they can stare vacantly at the walls, or moan and groan all day and night, or – like the old woman with the babydoll – be lonely and frightened in their senility. If there’s no realistic hope of recovery, why do we do this? To me it seems cruel.

As a society, the cost is huge. Again, I stress that I do not suggest we start pushing wheelchairs out into freeway traffic. But as a society, the amount of resources that could be directed toward the future (such as raising healthier children) is instead used for . . . what, beside fighting a battle against an unconquerable foe, Death? Maybe it’s not so much to preserve our loved ones’ lives as it is to continue our denial of the inevitable.

Death is rarely comfortable. Yes, people do die in their sleep – but not usually. Many more die in an episode of brief but acute pain (heart attacks, trauma, etc.), and most die over a protracted period of pain due to disease or worsening failure of the worn-out organs (Read “How We Die" by Kevin B. Nuland.) This in itself is not completely bad: sometimes the period of pain is what enables the person to either gather the courage to meet his maker or become exhausted and just give up the ghost.

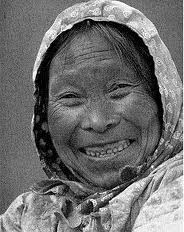

I’ve read that in bygone days traditional Eskimos and Inuits venerated their senior citizens, and that those same senior citizens, when faced with an extra cold winter and dwindling food supplies, would sometimes excuse themselves and take a long, one-way walk in the snow. It wasn’t an act of hopelessness: it was an act of love for the grandchildren. The grandparents would give up their lives to increase the chances of survival of their grandchildren.

I am NOT suggesting we ask our senior citizens to take long, one-way walks in the snow. I am suggesting that we, as a culture, change the way we look at life and death.

My Mother's Death

My mother died 20 years ago (literally in my arms, by the way, so for me this is not just a hypothetical, academic discussion.) She had beaten back cancer, but she finally succumbed. More than a year earlier, she was lying in a hospital bed with jaundice and looking every bit like a yellowed deflated human-shaped balloon. It amazed us – and I use that word intentionally, amazed – that she recovered, but she did, so I understand first-hand not to give up hope prematurely. Her fight was worth it, too, because her last year was my niece’s first, and the two of them spent a lot of that year cuddling and napping together. I am sure that spending time with her new granddaughter helped my mother ease herself out, and also the baby helped all of the family to watch our mother ease out. Not being flippant, but you know, the “circle of life” and all that. So, yes, I certainly do understand that there is still societal value to someone who can’t do much more than lie in a bed and consume medical resources.

After my mother died, I read Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’ On Death and Dying. In one part of it she explains the different ways family members typically deal with an imminent death. As I read those pages, there were paragraphs that described several of my family members exactly. It wasn’t like reading a horoscope that can fit many people: her descriptions were clearly distinct and spot-on. That was memorable for me, but not surprising. The part of that book that to this day I think about more often is how she said that the way people handle death is pretty much the same way they handle life. Wow. I re-read the descriptions of how people handled death in the family, couldn’t help myself from assigning my and my siblings’ names to specific paragraphs, and thought about how each of us approach life. Yes, pretty much the same. That idea has resurfaced repeatedly for me over the past 20 years.

Distance from Death

Again, looking back on pre-industrial cultures, we see two things about death not present in our modern lives. First, there was more of it. Much more frequently than they do today, mothers died in childbirth, children died of disease, men died young in hard or unsafe working conditions. Second, non-human death was part of everyday life: for example, people slaughtered their own chickens in their backyards. Today, for the most part, if someone doesn’t die from “old age”, it is considered unusual and premature, and most people have never slaughtered a single animal, farm or game, to cook for dinner. Driving past cold roadkill is not a replacement experience for killing an animal so you can eat it. We’ve distanced ourselves from the role of death in life.

Distancing ourselves from being dead is a great idea; being unfamiliar with death, not understanding, not feeling, that it is very much a part of life, is not very useful. In childhood we learn to grieve the death of family members, but we’re not taught to grieve the loss of family members. If we haven’t “been on speaking terms” with a sibling for 10 or 20 years, aren’t they already pretty much dead to us? We won’t talk to them, but yet we’ll drive across the country to go to their deathbed or funeral. Why? Right now take a moment to imagine the difference in reactions you’d get from people if you told them only “My brother died” or “My brother hasn’t spoken to me in 20 years.” To which would you hear the response, "I'm sorry for your loss." As a society, we put an unbalanced emphasis on the physical event of death.

Physical Death

The physical death is not something to be eagerly sought after, of course, but when it’s time, it is not such a terrible thing in itself. If you believe in a heavenly afterlife, then death is the beginning of a blissful adventure. If you believe you’re going to hell for eternity, well, another year or decade or half-century of human life is a very, very, very small percentage of eternity, so when you cross over isn’t much of difference. If you don’t believe in an afterlife, then you’re simply dead, and that’s that, and you will not be aware of any loss or regret or anything at all. Yes, of course death is a big event, but why - especially if we believe in an afterlife - is it so feared?

Is it the animal part of us? After all, it is the animal part of us that gives us perhaps our strongest instinct, the drive to survive. But the human part of us, the part that allows us - unlike other animals on Earth - to imagine the future, and to conceptualize and refine our beliefs, to guide our own thoughts . . . doesn’t some part of that give us the choice of quieting our own fears about the inevitable? Why don’t we do it more often? Why, as a culture and a society, do we sanction the opposite, the subtle propagation of fear of death? (Example: nowadays senility is called dementia because dementia sounds more like a condition, maybe even something temporary that might be cured, whereas senility has long carried the connotation of being a stage before impending death.)

A Good Day to Die

Over the years, I’ve gradually gained deeper understanding of the Sioux warrior Crazy Horse’s famous quote, “It’s a good day to die!” Variations of the phrase come up in other cultures, too. The Vikings come to mind quickly, as do the fictional Klingons. Warrior cultures that prize a “good death” in battle require that the warrior be fighting when he is slain, that he is fighting to live, fighting to conquer. The crucial part of dying in battle is not simply dying on a battlefield but putting forth the effort at fighting, trying with your last breath. So, you see, it is not about the warrior's death but how he lived right up until the very end.

A “good day to die”? It’s always a better day to live, but if you’re probably going to die, then, yes, it IS the same thing: a good day to live until you die. (Wiktionary says the phrase means “A belief that one should never live a moment of one's life with any regrets, or tasks left undone. Which would make today as good a day as any to die.")

Vaccinations

Perhaps the warrior cultures understand this because their familiarity with violence “vaccinates” them against the fear of the physical death. To somehow better their lives by taking land or treasure or whatever, they fight together for the common goal, brothers in arms, risking everything, battle after battle, surviving wounds and then going at it again, facing death repeatedly. I am not suggesting we all go a-berserzking, but most of modern society is too far insulated from death.

Think of how many people every day go up and down the highway with little or no thought of how close they might be to badly mangling their bodies or getting killed in a traffic accident. No, cushioned in our soft leather seats and stereo sound, we hurtle down the road with only vague imagery – if any! - of possible negative consequences. Most of us just haven’t seen or unintentionally tasted any blood spatter from a collision. It is a very real possibility that someday we may very well experience it, but most of us have no emotional “warm-up” events to help us fully imagine and emotionally prepare for it (or viscerally want to prevent it!)

By no means am I a daredevil adrenaline junkie, and I doubt anyone who knows me would describe me as exceptionally bold, but I have done quite a few things that have given me that now familiar moment of cold sweat. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve wrecked motorcycles (on and off road), and I’ve served as a firefighter (had a few hot ones!), been 100 feet underwater way out in the tropical ocean with a bloody nose, whitewater kayaked for a few years, and so on. I don’t and probably won’t ride a motorcycle anymore, and since I’ve spooked myself several times in whitewater I probably won’t paddle a river kayak anymore, and so on, but those exciting experiences did not make me afraid to do such things (cumulatively, they build confidence.) They did, however, give me “vaccinations” for the ultimate excitement, the upcoming Big Event. If you’ve ever needed to go to a hospital emergency room and felt lucky about being able to walk yourself in, you know what I mean.

Unprepared, ill-equipped, and mis-focused

So, most of us, with no first-hand “vaccinations”, eventually wind up involved with making decisions for a loved one’s final chapter of life. For most of us, it is the first time in our lives we have to deal with an imminent death and our own fears of death. For many of us, we are somehow a bit surprised that it is happening. (I’ve heard people say “Why is this happening to Grandpa?” and “If something happens to him . . .” Answer #1: because he’s 94 years old; answer #2: IF something? It is WHEN something! Also see Answer #1.) We react with ways we know, with habit, and only maybe with untrained emotional muscles. And most of us have never in our lives even considered that how we face death is pretty much exactly how we habitually face life.

Today, here, as a society, we put the emphasis on the end of a life and not how it was lived. Apparently we care more about the closing of a book than we do the final chapter or even the whole of the story. Sure, there’s usually a eulogy, but are they ever remembered? Are the eulogies ever celebrated in some way, like the way Vikings would sing songs of their friends who died in battle? Have you ever heard of a family member asking for a printed copy of the eulogy? What is more significant, that someone once lived and gave us memories and love, or that he or she - like all of us - aged and died? Why do we seem to care less about the fact that someone lived long enough to grow old than we do that we - naturally - will have to carry on without them?

When people visit their grandmother on her deathbed, do they give her a fist-bump or a high-five and say, “Way to go, Grandma! You lived well! Congrats on having a good life! I’m going to miss you, wish you didn’t have to go, but I’ll tell stories about how great you’ve always been to me!” No, with teary eyes we speak in hushed tones, and we’re filled more with sorrow for our own loss than with loving smiles for a life lived in a way that earned the love of the family. How does this help the one we profess to love let go of his or her completed and rapidly expiring life and gather the courage to move on into the unknown?

Dignity

As a society we like to talk about preserving old folks’ dignity for as long as possible, but in way too many cases that’s just a lie we tell ourselves, isn’t it? As the end nears we’re more caught up in our loss and the resultant changes in our family’s world than we are with helping our loved one have the modern, non-battlefield version of a “good death.” We hide like children in our illusions and delusions and rationalizations. As a society, we don’t keep many of our elders alive for their sake: we do it for our own, to save ourselves from facing our fears and questioning our values and putting our beliefs to the test.

Do you believe that as a culture and society we currently have emotionally-healthy attitudes about old-age death?

And if that old woman I mentioned earlier, the one who was clutching the babydoll, if she somehow temporarily escaped her senility, if she somehow had a moment of clarity and decided to slip down the hall and out the door so she could take a long, one-way walk in the snow . . . (which I'll bet is exactly what most people in nursing homes would have chosen to do when they were able to if they had somehow foreseen what they would become.) As a society, we’d stop her, wouldn’t we? We’d say her walk in the snow was “undignified, no way for someone to leave this world.” And then we’d put her in a fresh diaper, and restrain her in her bed, and leave her alone so she could talk with her babydoll again.

I think we’re the ones who have lost our dignity.