The Story of Ebola

Ebola Rampaging Through Africa

Between 2014 and 2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreaks in West Africa killed more than 11,000 people and proved fatal to 40 percent of those who contracted the disease.

Then, Ebola became rampant in the Democratic Republic of Congo, an outbreak the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a “public health emergency of international concern,” the highest level of alarm the agency has.

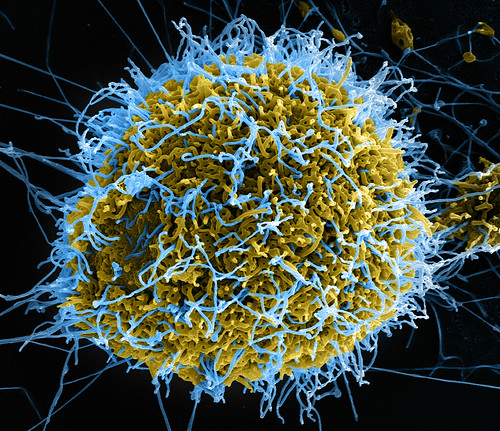

The Origin of Ebola

Ebola first appeared in 1976 in two separate outbreaks that occurred at the same time. One was in Sudan and the other in the Democratic Republic of Congo close to the Ebola River, hence the name.

The hemorrhagic fever crossed the species barrier in Africa from contact with infected primates, fruit bats, and other animals hunted for their meat. It is a severe ailment, killing anywhere between 25 percent and 90 percent of those that contract it; the average fatality rate is 50 percent.

There is no cure and, says the WHO, “outbreaks occur primarily in remote villages in Central and West Africa, near tropical rainforests.”

How Ebola Spreads

Human-to-human transfer of the virus comes about through contact with bodily fluids.

This can happen with direct transmission through broken skin or mucous membranes or indirect contact with areas contaminated with bodily fluids and wastes.

Burial rituals in which people touch the deceased are also a way in which the Ebola virus spreads.

Sexual activity can be how the disease is transferred from one person to another.

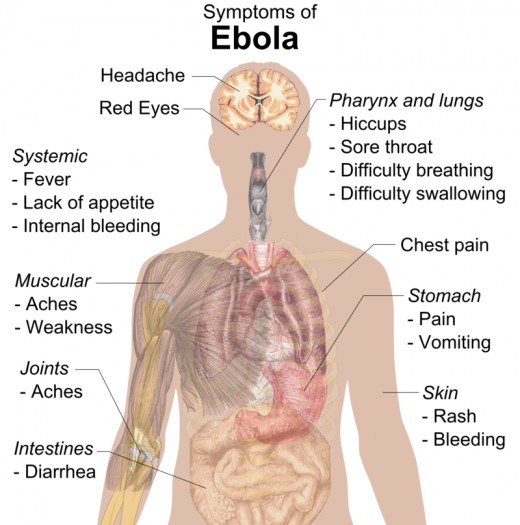

The Symptoms of Ebola

The first signs of the disease are relatively mild but soon become severe.

The incubation period after exposure can be as short as two days or as long as three weeks.

In its early stages, an Ebola infection might show up as flu-like symptoms – headache, intense weakness, muscle pain, and sore throat. During this phase it can look similar to several other illnesses such as malaria, typhoid fever, meningitis, or cholera.

Then comes the really nasty stuff, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, poor kidney and liver function. Later, patients start to bleed internally and externally, mostly through the nose, gums, and ears. It is not an easy death.

There is no known treatment other than re-hydration, what the WHO calls “supportive care,” and hoping for the best. More optimistically, the UN agency says “a range of potential treatments including blood products, immune therapies, and drug therapies are currently being evaluated.” In addition, a vaccine has been developed that seems to be effective in protecting people from getting EVD.

Patients are infectious as long as the virus is present in their blood. One man still carried Ebola in his semen 61 days after the onset of the illness.

Outbreaks in Africa

The first case of Ebola in 2014 occurred in the West African country of Guinea; it then spread to Liberia, and Sierra Leone. These are very poor countries with rudimentary health-care systems and primitive sanitation.

One case showed up in London, England carried by a refugee claimant and a doctor working in West Africa came down with the disease when he returned to Texas.

The WHO described this outbreak as the worst in history in terms of the number of infected people.

The Congo epidemic started in August 2018 and the number of cases and deaths has accelerated since then. As of this writing (July 2019), more than 2,500 people have been infected and over 1,600 have died.

As one outbreak is contained another pops up somewhere else. The BBC says “it is a gruesome game of whack-a-mole that appears all but impossible to win.”

Containing Ebola

The template for how to deal with Ebola can be found in Uganda. The central African country has been hit with four outbreaks of Ebola and they have all been treated swiftly and effectively.

First, the population has been well educated about Ebola and its symptoms to demystify the disease and deal with superstitions surrounding it. The result is that Ugandans are open about reporting Ebola-like symptoms.

Early detection of an outbreak is essential so a laboratory has been set up in Uganda so that samples can be tested and results known within 24 hours. A positive test triggers the sending of a team to the patient’s location to identify all who had contact with him or her. These people are tested as the entire chain of transmission is revealed. Those found to be infected are immediately isolated and treated.

An Ebola outbreak started in Uganda late in July 2014. All those in direct contact with patients were isolated for 42 days and their belongings burned. They received proper care and their possessions were replaced. Just 24 people were infected of whom 17 died, but the Ebola outbreak was snuffed out before it took hold.

The current strategy for tackling the disease is vaccination. When a patient is diagnosed, their relatives and friends are asked to go to a vaccination station for a jab. But, there are problems associated with this.

Many Ebola cases in remote villages are simply not reported. As well, decades of fighting in the DR Congo has created a deep mistrust of authorities among the people.

There is also an issue identified BBC’s Farai Sevenzo during the West Africa outbreak: “People are unwilling to go to hospitals to be screened even though early detection is the best hope of survival. They have seen that those who have been admitted rarely make it out again, dying in isolation without the comfort of their family around them.”

Conspiracy theorists are adding to the problem. One story that some believe is that Ebola is the result of a Western medical experiment that went horribly wrong. As a result, they are steering clear of Western health care. Another fiction is that there is no such thing as Ebola and that people are put in hospital so their organs can be harvested for Westerners who need them.

Isolation for Protection

Some people are advocating for quarantining entire communities if a case of EVD is found in them. The precedent for this is leper colonies that have been used to isolate sufferers since ancient times.

The WHO declared leprosy conquered in 2000 but there are still hundreds of informal colonies mostly in India. People isolate themselves in such places because of social ostracism associated with being a leper.

But, sealing off millions of people in places affected by Ebola, even if it was possible to do this, would condemn large numbers to death. WHO assistant director-general Dr. Bruce Aylward has said such draconian measures as quarantining entire nations “would be horrifically unethical.”

Bonus Factoids

- Kalaupapa Leper Colony on Molokai, Hawaii was opened in 1866. It once housed 8,000 residents and it is still operating with just half a dozen patients.

- In February 2019, a group of attackers set an Ebola treatment centre in the Democratic Republic of Congo ablaze. Fortunately, none of the patients was harmed. This followed a similar attack three days earlier on another Ebola treatment facility in which two people were killed.

- In February 2025, Donald Trump's Department of Government Efficiency cancelled funding for Ebola research. The outcry from medical experts led to quick reinstatement of the program.

Sources

- “Ebola Virus Disease.” World Health Organization, May 30, 2019.

- “Ebola in DR Congo: Fear and Mistrust Stalk Battle to Halt Outbreak.” James Landale, BBC, July 9, 2019.

- “Letter from Africa: Ebola Invasion.” Farai Sevenzo, BBC, July 29, 2014.

- “How Uganda Stopped Previous Ebola Outbreaks.” Hilke Fischer, Deutsch Welle, August 18, 2014.

- “Expert: We Can Control Ebola Spread.” Press Association, October 12, 2014

- “Congressman: Close Border to Ebola Countries.” Steven Nelson, U.S. News & World Report, July 30, 2014.

- “Battling Ebola in a Conflict Zone DR Congo.” Doctors Without Borders, February 2019.

The writer has no control over the placement of advertisements in connection with this article.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2019 Rupert Taylor