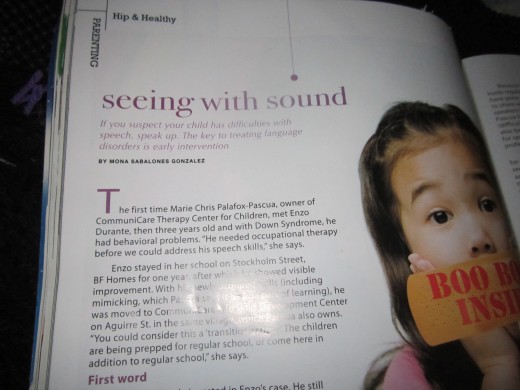

How to Help Children With Speech Difficulties

The first time Marie Chris Palafox – Pascua, owner of CommuniCare Therapy Center for Children, met Enzo Durante, then three years old and with Down Syndrome, he had behavioral problems. “He needed occupational therapy before we could address his speech skills,” she says.

Enzo stayed in her school on Stockholm Street, BF Homes for one year, after which he showed visible improvement. With his newly acquired skills (including mimicking, which Pascua says is a large part of learning), he was moved to CommuniCare Life Skills Development Center on Aguirre St. in the same village, which Pascua also owns. “You could consider this a ‘transition school.’ The children are being prepped for regular school, or come here in addition to regular school,” she says.

First Word

Marie was deeply invested in Enzo’s case. He still didn’t speak after one year, but she kept believing. Several strategies were applied, but progress could not be measured. Then one day, Enzo looked at Marie out of the blue and said “ball”. Marie broke down and cried.

“Children feel empowered when they can speak,” she says. “They realize it is a way of getting what they want.” Enzo saw a ball in a transparent zip lock bag, and he asked for it. It was handed to him like a trophy. Now six, Enzo, just before our interview, asked if he could go to the bathroom.

Do you have a child, or know a child with speaking difficulties?

Do you have a child, or know a child who has speaking difficulties?

A New Profession

Speech Pathology is a relatively new profession in the Philippines. The first school to offer this course was the University of the Philippines, and Marie was in its first batch of graduates in 2000. “We were only 23,” she says, “and a number of them went to the States after graduation.”

Only this year, the University of Santo Tomas opened a Speech Pathology course. There is also the Philippine Association of Speech Pathologists (PASP), with Board Director Ken Kristoffer Tort. The PASP certifies that a professor is a graduate of speech pathology and attends regular seminars. Parents should make sure their speech pathologist is PASP accredited.

Because the course is relatively new, PASP holds regular seminars by members who have gone abroad or attended a convention to share what they learned. PASP also invites speakers from overseas. To augment her work, Pascua has taken classes at UP in dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and reading, which has also become a component for communication for special children. Plus she cites the need for professors to do their own research.

Even for the children, learning needs to be constant. “Many parents of special children see school as a way of giving their child activities to do,” Pascua says. “But I tell them that it is more than that, it is an investment in their future. Parents worry that when they die, no one will care for their special child. But with new skills taught early in the child’s life, possibilities are maximized.”

Pascua says parents must act immediately if they sense that something is amiss. “At this stage, speech is most easily learned, whether a child is developmentally delayed or not. If a child starts too late, it is harder for him to learn to speak.”

A Larger Need

A child with speech difficulties will (usually) have problems in larger areas too.” At CommuniCare’s 350 school population, most have Down Syndrome or Autism Spectrum Disorder,” Tort concurs. Children perhaps with ADHD, swallowing difficulties, hearing problems, or even with a cleft lip or palate among others, may have speech difficulties. Tort, aside from serving as PASP board director, is involved with UP Manila’s Clinic for Therapy Services (CTS) , where he supervises SLP interns, and is Chief speech-language Pathologist of We Speak Specialized Intervention, Inc. in Ortigas Center, Pasig. He is also a consultant SLP at the Alternative Learning Resource School – Philippines (ALRES-Philippines, a special school) in Quezon City.

The muscles used for swallowing chewing and breathing are the same muscles used in speech. “Children with Down Syndrome have weak muscles, even oral muscles,” Pascua says. “When they drink milk from a bottle, there is spillage and drool because these muscles are hard to control – the same muscles used for speech. And for some children, a cerebral problem may affect their lungs, so they have weak cries. You need air to make sounds. When older, there may be trouble with prolonged phonation.”

Dealing With Disorder

“The hardest thing for parents to deal with is denial,” Pascua says. “But the longer they go through that, the more precious time a child loses. The first seven years are critical to learning, especially for language. When parents come to CommuniCare, they are past denial. The good thing is they meet the parents of their child’s classmates, become friends, and are one another’s support system.”

Pascua says that a job like hers is filled with laughter and tears. “You name it, we teachers have had it,” she says. “My hair has been pulled by children, I have gotten punched, because like everyone else, sometimes the children have moods,” she says. “So there are times the teachers – not the children – have time out.”

Children with difficulty speaking

Tort agrees: “Being a speech-language pathologist is tough. You need energy, dedication, commitment and skill in order to provide the best service possible. Each time I feel tired and think of giving up, I think of my students – how they laugh, how they smile, how they kiss and hug me each time they come. And then I would know that the exhaustion is all worth it.”

Marie relates, “One teacher asked the children to name something yellow. One child said, ‘mango’ and then the next child said, ‘mango juice.’ Another time, at a marine aquarium, one child noticed how one fish seemed different from all the rest. He asked, ‘Mama, does that fish have Down Syndrome, too?’”