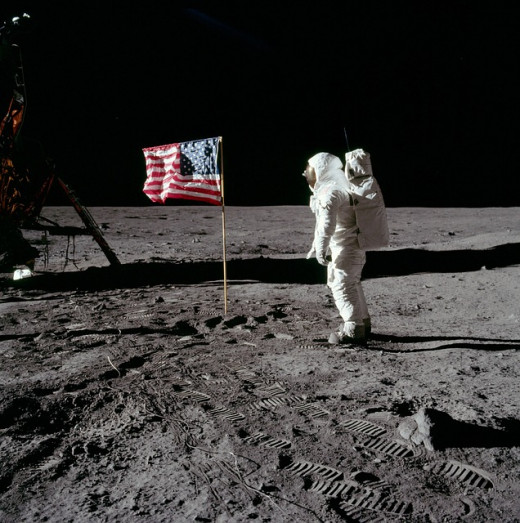

United States national flag

The United States’ national flag is the most familiar of our national symbols, perhaps the most revered, yet also among the most hated. Because the familiar design clearly says “America,” whatever feelings people have for America—however they define it—are transferred to the flag. Similarly, people in foreign nations view the United States flag as a symbol of democracy, liberty and prosperity or as a symbol of American greed, arrogance and imperialism.

But 21st-century attitudes towards the Stars and Stripes is but a tiny part of the story of this powerful symbol.

United States flag nicknames

The United States flag has at least three common nicknames:

Stars and Stripes—Though it’s the most popular nickname, no one knows its origins.

Star-Spangled Banner—This name came from the poem written by Francis Scott Key in 1814. This name is sometimes applied to the particular design—or even the particular flag—that inspired the national anthem.

Old Glory—This name was coined by Captain William Driver, captain of the Salem whaler Charles Doggett, in 1831 as he was setting out on the mission that would climax with the rescue of the mutineers of the Bounty. (Many websites incorrectly list the captain’s name as Stephen Driver, for some reason.)

The flag is also sometimes referred to as “the red, white and blue.”

Design of the United States flag

The United States national flag is a tricolor design; in other words, it features three colors—red, white and blue. These are three of the most common colors used in flag designs around the world. Green and yellow are also common colors, but are used primarily by “third world” countries—nations in Africa, parts of Asia, South America and Oceania.

The colors red, white and blue were clearly borrowed from English flags, many of which featured red, white and blue stripes. A few flags were inspired by the United States. The one that most nearly resembles the U.S. flag is Liberia, except that it features eleven stripes instead of thirteen and a single star in the canton.

The design of the U.S. flag features thirteen horizontal stripes—seven red and six white—and a blue canton (a rectangular area in the upper left corner) with 50 white five-rayed (or five pointed) stars. There have been four primary changes in the design:

1) The first official flag had thirteen stars, and all subsequent designs added a star for every state that joined the union.

2) The second official flag had fifteen stripes, though all others have featured thirteen.

3) An official pattern for the arrangement of the stars was adopted in 1912.

4) The design and color were standardized in the 20th century, with specific shades of red, white and blue specified. Flags of the 19th century varied greatly in the shades of red and blue, width-to-length ratio and even the number of points on the stars.

Still, no official proportions—the ratio of width to height—have ever been specified. In 1959, Presidential Executive Order 10834 specified a ratio of 10:19—a flag nearly twice as long as it is high—for certain military uses. However, the U.S. government buys and uses flags in several other proportions (2:3, 3:5, 5:8) for various civilian and military uses.

The national flag is sometimes trimmed with gold fringe, generally for military or decorative purposes.

Symbolism of United States flag

All flags have symbolic value, whether it’s prescribed by law or popular tradition. Some flags have both legal and popular symbolism.

There is no official symbolic description of the U.S. flag. However, the colors red, white and blue have the following meaning on the Great Seal of the United States:

Red: Hardiness and valor (bravery)

White: Purity and innocence

Blue: Vigilance, perseverance and justice

On other flags, the color blue sometimes represents water or sky, but it’s generally seen as a symbol of peace. White is frequently used as a symbol of purity, righteousness or aspirations. Red—the color of blood—is a traditional symbol of war, military might or suffering.

The thirteen stripes on the U.S. flag represent the thirteen colonies that united to form the United States, while the fifty stars represent the fifty states.

United States flag protocol

The national flag can be displayed any day, but it’s especially appropriate to display the flag on the following days:

- New Year’s Day, January 1

- Inauguration Day, January 20

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, 3rd Monday in January

- Lincoln’s Birthday, February 12

- Washington’s Birthday, 3rd Monday in February

- Easter Sunday (variable)

- Mother’s Day, 2nd Sunday in May

- Armed Forces Day, 3rd Saturday in May

- Memorial Day (half-staff until noon), the last Monday in May

- Flag Day, June 14

- Independence Day, July 4

- Labor Day, 1st Monday in September

- Constitution Day, September 17

- Columbus Day, 2nd Monday in October

- Navy Day, October 27

- Veterans Day, November 11

- Thanksgiving Day, 4th Thursday in November

- Christmas Day, December 25

- The birthdays of States (date of admission) and on State holidays.

As you can see, four of these holidays commemorate wars or Military’s forces (highlighted in light red), while four recognize specific people (light yellow).

The U.S. flag is generally taken down at night. However, the flag flies 24 hours a day at the following locations, by Executive Order:

- Betsy Ross House (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

- White House (Washington, D.C.)

- U.S. Capitol (Washington, D.C.)

- Washington Monument (Washington, D.C.)

- Marine Corps War Memorial (Arlington, Virginia)

- Battleground in Lexington, Massachusetts (site of first shots of the Revolutionary War)

- Winter encampment cabins (Valley Forge, Pennsylvania)

- Fort McHenry (Baltimore, Maryland)

- Star-Spangled Banner House, where the flag that flew over Fort McHenry was sewn (Baltimore, Maryland)

- Jenny Wade House (Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; Wade was the only civilian killed at the battle of Gettysburg)

- USS Arizona Memorial (Pearl Harbor, Hawaii)

- All custom points and points of entry into the U.S.

The U.S. national flag is sometimes flown at half-staff—raised just halfway up the flagpole—to honor an individual who has died, usually an important government official such as the president. The flag may also be draped over the casket of any citizen, though the honor is usually accorded veterans or highly regarded state and national figures.

United States flag controversy

Although one seldom hears pleas to change the United States flag, it may be the most controversial of our national symbols. The United States’ national flags have always been somewhat controversial, from the designs that flew over thirteen states to the latest version, with 50 stars.

The following three issues account for most of the controversy:

1) Symbolism

2) Treatment

3) Association with Other Controversial Symbols

Symbolism covers a vast amount of territory, including what the flag means to any of the United States’ more than 280 million citizens. Many people associate such problems as racism, poverty, unjust wars, political corruption, or corporate greed with the U.S. flag. Such people may ask two questions:

What does the U.S. flag represent?

Who does the U.S. flag represent?

Thus, poor places to look for an American flag include Indian reservations, where Native Americans were confined by the “Great White Father” generations ago, and urban ghettos people largely by minorities.

Other people see the flag as a symbol of freedom, liberty, prosperity or righteousness. For them, the controversy lies not with the flag but with the way other people treat it.

Treatment (or mistreatment) generally goes hand-in-hand with symbolism; people who do not like the flag for one reason or another may treat it in a disrespectful—and controversial—manner. However, some people who don’t have strong feelings about the flag may nevertheless exploit it as a tool in making a statement.

One of the most powerful statements ever made at the Stars and Stripes’ expense occurred at the 1968 Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City. As the Star Spangled Banner played, two Olympic athletes—John Carlos and Tommie Smith—raised gloved fists in a “black power” salute to call attention to their disgust with racism.

Treatment also includes flag profanation, or physically desecrating the flag. The best known method of flag desecration is burning, which was especially popular during the Vietnam War. Many people view flag burning as a means of expression protected by the 1st Amendment. Others argue that it’s unacceptable behavior and may even advocate harsh prison sentences for burning the flag. This is an issue that especially pits conservatives, who hate flag burning, against liberals, who are more tolerant of it.

Treatment includes trying to force one’s beliefs about the U.S. flag on others. Ironically, citizens who try to “ram the flag down other people’s throats” or dictate how others treat the flag may defeat their own purpose by increasing animosity towards the flag. We might call this force-feeding, which can include flag displays that some people find a little obnoxious—like thousands of people waving cheap, miniature flags at football games. Such people are often called “flag wavers” and are often stereotyped as “rednecks.”

Politicians are notorious for exploiting the flag. Many use it as a form of propaganda, suggesting that their respect for a hallowed symbol (the flag) makes them respectable, or that the flag marks them as a leader who should be obeyed. Corrupt politicians often use this strategy to divert attention from their corruption.

One particularly obnoxious trick is to lead a group of people in saluting the flag or saying the Pledge of Allegiance. If people follow along, it looks like they respect the politician who’s leading the ceremony. If they don’t follow along, the politician on the podium may criticize them as unpatriotic, or un-American. It’s a no-win situation—and a cheap trick.

Using the flag to deceptively boost your support or to divert attention from your problems is popularly called hiding behind the flag. The first President George Bush was widely ridiculed for hiding behind the flag, and President George W. Bush is even worse. A constitutional amendment banning hiding behind the flag would be far better than one banning desecration—which is far less common and causes far less damage. Unfortunately, it would be nearly impossible to prove in court that a politician was “hiding behind the flag.”

But the worst force-feeding has generally taken the form of laws that punish people who don’t show the flag what authorities consider the proper respect. People have gone to prison for refusing to salute the flag!

But flag propaganda isn’t limited to seedy politicians. The government and Big Business constantly promote the national flag in advertisements, the media, patriotic events and other forums calculated to advance their agendas.

The U.S. flag is also controversial because of its association with other symbols, particularly the Pledge of Allegiance. The ongoing controversy over the Pledge especially reflects on the flag. Many people look at the words “under God” in the flag pledge and the national motto, “In God We Trust” and conclude that the U.S. flag is being transformed into a religious symbol.

Olympic Snots

One interesting and very obnoxious flag tradition that is hard to understand is the custom of not dipping the American flag to host nations at Olympic Games ceremonies. No other nation follows this custom, which is incredibly rude and arrogant.

Many sources say this custom began when the United States Olympic team refused to dip its flag to German host Adolph Hitler in 1936. Hitler was a very evil man, and anyone who didn’t salute him should be praised. But the custom of not dipping the flag goes much farther back than that. In fact, it’s possible the Hitler story has been promoted to make this arrogant custom appear somehow noble.

In fact, the Untied States didn’t dip its flag to the host (England) in 1908, at the very first games to feature a parade of nations. However, this may have been personal—the American carrying the flag was Irish, at a time when the Irish weren’t terribly fond of the British.

The United States team politely dipped its flag at the Stockholm Olympics in 1912 and the Paris games in 1924. They carried the flag “borne aloft” at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, when the games resumed after World War I.

But USOC president Douglas MacArthur insisted on following military protocol at the 1928 Amsterdam Games. That meant the flag should be dipped to no one, not even the U.S. (You can’t get any more arrogant than snubbing yourself!) MacArthur went on to become one of the most famous generals of World War II.

However, the flag was again dipped to New York Governor Franklin Roosevelt at the 1932 Lake Placid Winter Olympics and to U.S. Vice President Charles Curtis a few months later at the Los Angeles Games. Four years later, America’s Olympic athletes snubbed Adolph Hitler before the world was swallowed by World War II.

Since the Olympic Games resumed in 1948, the United States has stubbornly refused to dip its flag to anyone. One of the tackiest Olympics ever was the 2002 event at Salt Lake City, which was transformed into a patriotic event that made the United States look very selfish in the eyes of the world. After all, other nations also suffer tragedies, which they do not exploit during Olympic Games—probably because they don’t want to embarrass themselves in front of millions of TV viewers around the world.

United States flag companion symbols

The Stars & Stripes is closely associated with most patriotic symbols, especially the Pledge of Allegiance, national anthem (The Star-Spangled Banner), Flag Day, 4th of July and Marine Corps War Memorial.

The Pledge of Allegiance is directed to the national flag. The national anthem was inspired by an early American flag, and is usually played while the national flag is flying. Flag Day celebrates the adoption of the first official United States flag.

The first Flag Day was observed on June 14, 1877, the 100th anniversary of the Continental Congress’ adoption of the Stars and Stripes as the official flag of the United States. Congress asked that all public buildings fly the flag on June 14. The idea quickly caught on and many people wanted to participate in waving the flag. One early supporter ws B. J. Cigrand, a Wisconsin schoolteacher who wanted to establish June 14 as a holiday, “Flag Birthday.”

In May, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson issued a Proclamation establishing Flag Day (June 14) as an official celebration. The holiday was further promoted when President Harry Truman signed an Act of Congress designating June 14th of each year as National Flag Day in 1949.

July 4, of course, celebrates America’s birthday and is our most important patriotic holiday. Memorial Day and Veterans Day commemorate people who fought in various American wars, and the Marine Corps War Memorial was inspired by a flag that was planted on the island of Iwo Jima—and the men who planted it—during World War II.