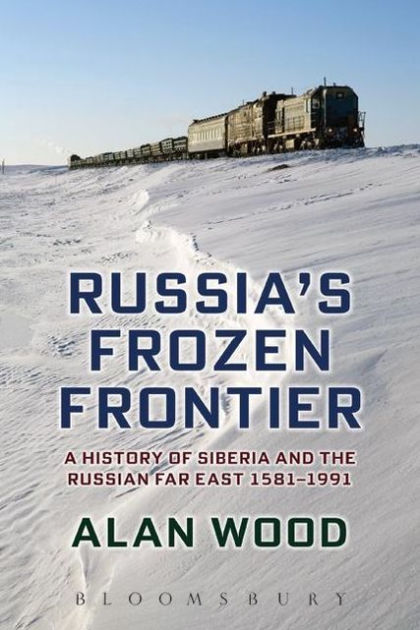

A History of Siberia and the Russian Far East Review

Siberia, as Alan Wood states in his book, "Russia's Frozen Frontier: A History of Siberia and the Russian Far East: 1581-1991" has two great popular representations of it: as a frozen wasteland, and as a huge open-air prison, to which were sent the dregs of European Russia but even more importantly its rebels, dissidents, and revolutionaries, to live in arduous and murderous conditions of slavery and imprisonment. Neither, as Wood notes, is per se wrong - Siberia has been used for just such an awful purpose by Moscow, and it truly is a forbidding and terrible environment, although one with far more diversity than is generally given credit for. At the same time that Siberia has been a vast open air prison, it has also been a place of liberty for peasants hoping to find a new life, for believers of the Old Faiths fleeing Russian religious reforms, for skilled craftsmen and professionals: it also continues to be a home for the oft-forgotten Siberian indigenous peoples. Wood shapes the long, epic, history of Siberia into a tale which is comprehensive and humanizing, one with if often dealing with the misery of the region, also covers its triumphs and its long history of changes and evolution.

Chapters

Chapter 1, "The Environment: Ice-Box and El Dorado" sets forth the contrast of Siberia, as both a land of great resources (furs, agriculture, gold, oil...) and terrible human suffering and privation. It covers the climate and geography, and the various regions that make it up. The administrative borders of Siberia have varied greatly over time.

Chapter 2, "The Russian Conquest: Invasion and Aftermath" picks up with the initial Russian foray into Siberia, by the little-known and mysterious figure Yermak Timofeevich, who invaded and defeated the Sibir Khanate, commencing the Russian drive to the East. Many myths have grown up around this, but regardless, once the Russians defeated Sibir they advanced with lightning speed, having reached the Pacific by the 1640s, in constant search for furs, which formed the centerpiece of an increasingly diverse economy. Along the way they built extensive fortifications to counter resistance and secure their control. Population grew on the back of military and government personnel establishing stable conditions for future settlement: it was also already serving as a land for exiles, such as the old believers who refused to bow to reforms in the Orthodox church.

Chapter 3, "The Eighteenth Century: Exploration and Exploitation", covers the great scientific expeditions launched by Russia, such as the Great Northern Expedition and the First Kamtchaka Expedition, when the Russians explored the North-Western Pacific. Covering both the broad sketches of the expedition, and the writings, reports, and experiences of the travels and peoples as provided by individual participants, the chapter also delves into why certain writers wrote what they did in response to the same conditions which were reported in very different ways. It also covers the first large scale industrial development, principally mining and ironworks, and the evolution of the exile system.

Chapter 4 "The Nineteenth Century: Russian America, Reform and Regionalism" examines the reforms to the dysfunctional Siberian region of the Russian Empire carried out by the exiled Russian administrator Speranskii, who greatly modified the bureaucratic structure of Siberia - although the author seems to doubt about how much this impacted conditions on the ground and just how revolutionary these changes were. In addition it also briefly looks at the rise and decline of Russian America, that foray across the Pacific onto the American continent. It also relates political developments from below, with the formation of Siberian regionalist agitators, their concerns (they helped formulate the idea of Siberia as a colony of Russia), and how they hoped to reform Siberia. This Siberia also grew for the last time, with the Russian annexation of Amur from China, providing a large and (relatively) temperate region.

Looking at a more sad subject, Chapter 5, "The Native Peoples: Vanquished and Victims" casts an eye on the bedraggled fate of the Siberian natives, as well as their original condition. Although a diverse people, there were certain elements that were generally common to the Siberians, who were unique and neither truly Asiatic nor European. There were a great number of different ethnic groups, who tended to rely upon hunter gathering, either from the land or the sea. Many were partially or completely nomadic. The Soviets had vigorous debates to deal with their level of development in Marxian terms, concerning whether some groups with feudalistic, primitive-communist, or beginning to become capitalist. They did have limited artisanal production of goods ranging from textiles to iron. War was not uncommon, but was further exacerbated by the arrival of the Russians. Shamanism and animism were an integral part of their religion, which the Russians had difficulty stamping out. Mikhail Speranskii’s attempts in the early 19th century to improve their conditions generally failed, as it was still from a state-centric effort which prioritized imperial Russian interests first. Siberian regionalists were thus still able to decry the treatment of the natives and to argue for defense of their remnants in the end of the 19th century.

Chapter 6, ‘Fetters in the Snow’: The Siberian Exile System" covers both the numerical facets of the Siberian exile system, its victims, and how it operated. Exile had a long history in Russia, and it was used to attempt to help settle Siberia, and to an extent was even claimed as merciful, as it was an alternative to capital punishment. In practice the problems with the system meant that it failed to effectively settle Siberia and led to widespread suffering, for both its unfortunate victims (especially those sent to Sakhalin), and for the other inhabitants of Siberia who suffered because of it. Attempts to reform it never really managed to correct the inherent failings. The majority of exiles belonged to two categories, criminals, and administrative exiles: the latter were those who were exiled due to decisions on the part of their collective communes, or previously the tsar or Serfs' masters, sending the unwanted or undesirable to Siberia. There were also small groups of political prisoners and exiled nobles. Exiles, until the railroads arrived (with their own terrible conditions) had to brave harsh marches to their destination, undergoing terrible journeys. They organized themselves, with tacit state approval, into their own communal governments, the artels, brutally enforcing their own laws and orders and negotiating with their guards. Upon their arrival at their destinations, these communes dissolved, and it was common for prisoners to revert to their old ways, terrifying the local communities with murder, rape, theft, and sadism.

Siberia played an even important role in Russia at the end of the Tsarist Empire, as explained in Chapter 7, "The Last Tsar of Siberia: Railroad, Revolution and Mass Migration". The construction of the Trans-Siberia railroad (not uncontroversially, being faced with a variety of, often sound, arguments against it and with a variety of regionalists opposing it as another project of Imperial Russia to subjugate Siberia), although not succeeding in saving the Romanov dynasty and failing to ensure Russian imperial goals in the Far East, was highly important for economic development. Siberia grew too hugely in agricultural terms, with millions of free peasants emigrating there, with a highly important butter industry and large grain exports. Industrial projects blossomed in the southern part of the region, driven by the arrival of skilled craftsmen. Siberia as a whole was rocked by the 1905 revolution, with order breaking down and socialist revolutions in many cities, helped by rebellious soldiers. Siberian peasants also engaged in revolts. The Tsarist Government's encouragement of future migration to the region was driven by the hope that with the creation of an independent yeomen peasant class, it would be able to secure political stability: in this, it failed. Instability continued with massacres of striking miners, and it was from Siberia that Rasputin, a mad "holy" peasant or charlatan, who so reduced the prestige of the Romanov Dynasty, hailed as well.

The collapse of Tsarist authority from WW1 defines the next chapter, Chapter 8, "Red Siberia: Revolution and Civil War", where Siberia dissolved into a variety of feuding political groups. There were diverse political groupings in Siberia, but it was a small minority, the Bolsheviks, who were the most united, disciplined, and powerful force. Initially quickly gaining control of the region, unpopular policies like crop confiscations and the problems of governing the huge territory led to weakening authority, which shattered when the escaping Czech legion, leaving the Eastern Front to fight in the West, seized de-facto control of the Trans-Siberian railroad following a botched Soviet attempt to disarm them, and when Western Allied forces established themselves in the Far East. White (anti-revolutionary movements) sprung up in their wake, many of them being sadistic and brutal local warlords, and all being relatively disunited and lacking popular legitimacy. The Bolsheviks ultimately defeated them and regained control over Siberia, including the temporary buffer state they had established of the Far Eastern Republic.

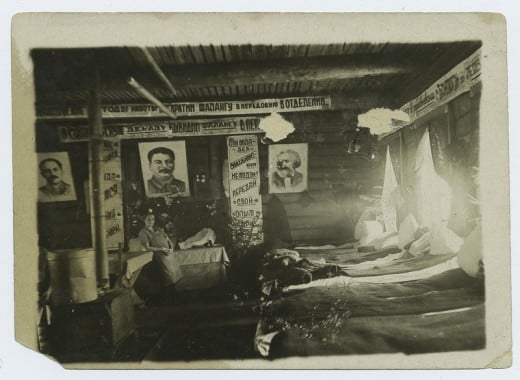

Unfortunately, things did not become happier for Siberia, as elaborated by Chapter 9, "Siberia under Stalin: Growth, GULag and the Great Patriotic War". Siberia benefited from a Soviet economic liberalization in the 1920s with the New Economic Policy which benefited its agricultural economy, assisted by favorable local political leaders and international trade links in the Far East. Stalin's decision to tour this region led to his decision that the rich peasants that resulted from this, the Kulaks, were sabotaging the Soviet socialist economy, and led to a brutal campaign of liquidation against them that exploited class divisions in the Russian countryside to brutally isolate and forment class war against them, enabling a campaign of collectivization of land. The Soviets did do more to attempt to help the Siberian native peoples, some of it amusing (such as translating Communist literature into languages which had no vocabulary for much of the content expressed), but well intentioned with some efforts to preserve their autonomous traditions or to elevate their social conditions. Industrialization was also vital under Stalin, which catapulted Siberia into a major industrial region of the USSR, growing much faster than other areas with massive development of heavy industry and infrastructure. It was also marked by what was in many ways the companion of this, with the GULAG, the vast network of brutal prison camps which exploited prisoners, be they political, criminal, or quite commonly, innocent, for labor. Although not intended for genocide, they had brutal conditions which led to vast amounts of death, with millions at a time suffering in it. When the Second World War arrived, Siberia played a vital role in providing fighting formations, geographic space, resources, supplied, and huge quantities of war material that would be vital to Soviet victory.

Another half decade of Soviet control continues in "Siberia since Stalin, 1953–91: Boom, BAM and Beyond". The GULAG ended with the death of Stalin, driven significantly by the resistance of its own members to their continued imprisonment, despite massacres against prisoners. Siberia boomed with the production of oil and gas production, sending huge numbers of workers there to benefit from high wages in pulling forth the black gold from the ground, although they suffered from the cold and primitive living and cultural conditions: the vast rivers of the region were harnessed to produce electricity for the country, despite the dangerous environmental effects of both. Agriculture generally did not succeed as much despite some ambitious projects, although there were some successes in the Altai with the help of agrarian scientists. Siberia in fact became a highly important scientific region, with the establishment of scientific cities which were intellectually vigorous and important centers for the humanities and technology. The Trans-Siberian railroad was also complemented by the vast new Baikur-Amal Mainline, thousands of kilometers long and hundreds of kilometers north of the Trans-Siberian, an impressive transport project which in many ways matched the Trans-Siberian's effects: political failure, but an important base for future economic activity. However, many of the same problems as found in the past continued to exist, such as widespread criminality, lack of development of human cultural infrastructure, environmental tragedy, and discontent from indigenous peoples. Regionalists continued to draw attention to these subjects, although never gaining enough critical mass or power to really make any significant changes. Siberia in other words, continues to be in the subservient political position to the Russian state which it has always had.

The book's afterword re-affirms the importance of Siberia to Russia and Russia's importance to the world: it is the author's hope that he has done something to help place it better into attention, and he calls for the continued study and understanding of its place in history and the future.

Suggestions for future reading and notes sum up the text.

Review

Concise and humorous, A History of Siberia and the Russian Far East spans an impressive length of time, and inherently a [i]very[/i] impressive breadth of territory - the vast region of Siberia, larger in size than all of Europe. To do so in the span of just a few hundred pages might appear hubristic, but Alan Wood has managed to paint, in as he admits of course, broad strokes, a complete and intriguing history of this incomprehensibly large and alien territory. Covering both the normal known facts about Siberia, about its vast prisons in which poor and destitute (if not always innocent) souls were afflicted with horrifyingly brutal and chilling (quite literally) punishments in this harsh land, or its build up of heavy industry and vast resources, it also delves into particular facets of its social life, into its political ideas, and into the existence of the indigenous people, often forgotten about in the presence of the Russian invaders from the West. Throughout, the author writes with a tone of deep compassion and humanity, and one which can be wry and humorous at times, complementing, rather than detracting, from the many tales of woe and misery which dot the pages. Although the writing style's informality can sometimes startle those used to reading academic texts, it does so in an accomplished and good way: clearly it is not due to a lack of experience of education, as shown by the author's skilled writing style and excellent, multi-lingual vocabulary. There are also a number of quite good figures, pictures, and illustrations.

In particular I adore the chapter on the exile system, when under the Tsars Siberia served as a point for a vast exodus of criminals, dissidents, and those who were simply unwanted, supposed to be settlers for the vast reaches of Siberia. In its goals, this failed, but there are some truly fascinating descriptions of how the system worked and of the social organization among the prisoners, who formed their own communes and governments, tolerated by the government and serving as parallel administrations to that of the official state. The exploration missions mounted by the Russians, such as the Great Northern Expedition, contain tremendous amounts of personal details and ethnographic accounts, matching a similar level of detail and interest in the native peoples of Siberia, whose customs and the impact of Russian colonization upon them receive documentation in their own chapter. Economically, industrial developments seem a favored topic of the author, who from the construction of the first cottage industries in Siberia in the 17th century, to Peter the Great's industrialization projects, to the Trans-Siberian Railroad, to the vast Soviet industrialization drives, has ready information about the economic development of the territory.

Obviously quite likes Siberia and feels a deep sympathy for the region and its many travails throughout history. This is obviously good in the context of his depth of feeling and the amount of research he has done on the subject, but it can also create some distortions in the text. Specifically, the author spends a very lengthy amount of time upon Siberian regionalism, autonomy, and independence movements - this despite that he admits that they never really gained any significant traction in the region. While they are fascinating, his unabashed admiration for them can detract from a clear picture of the actual political forces at work in Siberia. Whether I would classify it as a drawback, I am unsure - certainly it is a facet of its political life that deserves recognition - but at the same time it is an element of the author's thinking and interest that has to be taken into account by the reader.

Furthermore, there is nothing about the region since the collapse of the Soviet Union (noted in the title of course, perhaps Wood will release an updated version eventually with the more recent history), and the author's interests tend to concern political, economic, and ethnographic concerns, with little from other subjects - cultural production from Siberia, its military developments and geostrategic role to Russia and the USSR (although this is somewhat noted on concerning the Baikal-Amur Mainline), government institutional developments that impinged upon the common folk outside of the vast prisons of the GULAG or the exile system, infrastructure beyond the railways, and to some extent ethnographic information and scientific research upon the region itself. Clearly he as anxious to maintain a certain degree of brevity (although he needn't have been so troubled - the book is only around 300 pages long, much shorter than other comparable manuscripts), but this has inevitably caused certain aspects to be lacking.

Overall, it forms a good introduction into Siberia, providing a clear and consistent tone and message. Siberia has been a region which has been ruthlessly exploited by the central Russian state in Moscow, which has endured unbelievable cruelty and hardship because of this, both for its Russian and indigenous inhabitants, and yet which has also concealed a diversity of experiences and even liberty and success which is forgotten. For those interested of course in the history of Siberia, in broader Russia, in social history in Russia, indigenous tribes, the exploration of Siberia and the Northern Pacific, and a variety of miscellaneous topics, there is plenty to learn and be intrigued by.

© 2018 Ryan Thomas