African American Liberation and Transformation: Self-Actualization through Literacy and Education

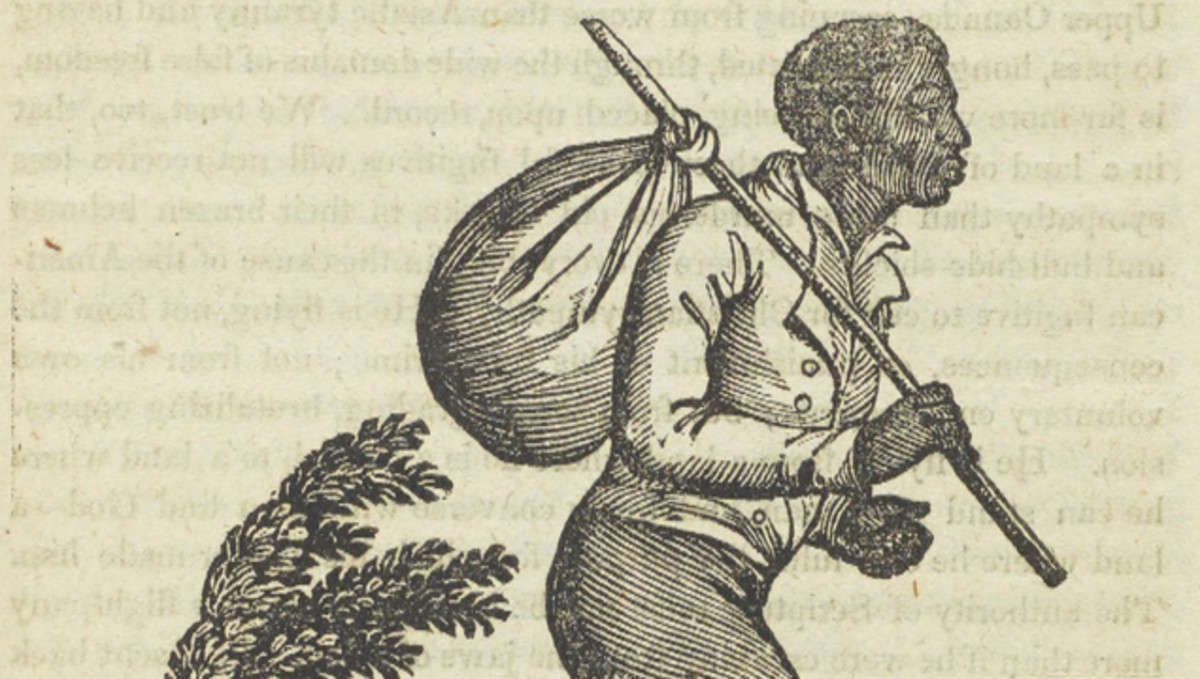

Before the Emancipation Proclamation, one of Frederick Douglass’s most passionately expressed values was the pursuit of knowledge and literacy. He said, “once you learn to read, you will be forever free,” and “knowledge makes a man unfit to be a slave” (The Frederick Douglass Organization, 2015). Thus, Douglass argued that African Americans could liberate themselves from slavery through psychological transformations via acquiring literacy and knowledge. Immersing oneself into the logomachy of official politics, law, and journalism is to create an “I” for oneself—to find his or her unique voice. The power language harnesses, according to social activists—has the power to make significant social changes in the practices and customs in United States such as overthrowing the institution of slavery. Into the 20th century, Douglass’ values of literacy and education survived in the writings, lectures, and essays of several African American scholars—perhaps none of them as influential and inspirational as W.E.B. Du Bois, whom exemplified and carried on Douglass’ vision and legacy of “an exemplar of leadership and its virtues” for the African Americans (Sundstrom, 2012). Just as his predecessor, W.E.B. Du Bois’ highly valued the acquisition of literacy and education for African Americans.

W.E.B. Du Bois’ Color Line and the Talented Tenth

“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line” (Du Bois, pg. 620). The color-line, according to Du Bois, is “a veil that both divides society and makes black people invisible” (Macey, 2001). Du Bois further contends that black experience is “characterized by the phenomenon of double-consciousness,” which in other words means African American individuals live in a dialogic state of mind: one side is white while the other side black (Macey, pg. 103). In the dialectic worldview, according to the literary critic Paul Gilroy (1993), double-consciousness captured “both the core dynamic of racial oppression and the fundamental contradiction experienced by the people of the black diaspora” (Gilroy, 1993).

For Du Bois, crossing the color-line—and ultimately liberating oneself from racial oppression—was accomplished through literacy and education. In 1903, Du Bois argued in his essay, the “Talented Tenth” that appeared in The Negro Problem, that political and civil equality of African Americans was related to higher education (Talented Tenth, 2014). He argued that “African American teachers, professional men, ministers, and spokesmen, who would earn their special privileges by dedicating themselves to ‘leavening the lump’ and ‘inspiring the masses’” (Talented Tenth, 2014). Ultimately, Du Bois viewed education as a movement from darkness to light in the sense that education could enlighten oneself intellectually but also physically, meaning that African Americans could abandon their perceived inferiority— blackness— for socially advantageous elitism—whiteness.

Du Bois’ idea of the talented tenth was created in direct contrast to Booker T. Washington’s promotion of industrial training for African Americans. Du Bois was afraid that African Americans would always remain second-class citizens or worse if they were not inspired to become creative and critical thinkers. The industrial training would dampen their spirits and numb them to true political and social equality. Ultimately, for Du Bois, it would signify a return to hard and unfair labor if African Americans did not pursue literacy and education because only through the latter could individuals challenge racial oppression in the arena that mattered most: the logomachy.

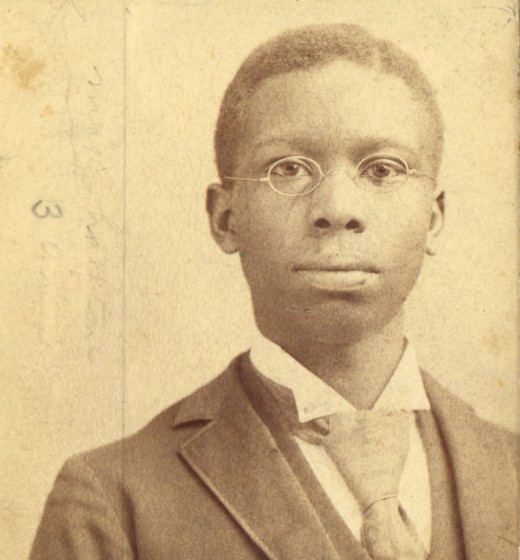

Paul Laurence Dunbar, the “Poet Laureate of the Negro Race”

Perhaps no other African American poet during the early 20th century crossed Du Bois’ color line quite like Paul Laurence Dunbar. Even Du Bois’ contender in African American politics praised Dunbar by dubbing him the “Poet Laureate of the Negro race” (Gates, McKay, pg. 884). His ability to both “feel the Negro life aesthetically” and “express it lyrically” imbued his verses with a tone that was both serene and genuine, a mood that was both empowering and melancholic, and a voice that was both white and black (Gates, McKay, pg. 884). Ultimately, Dunbar represented a perfect agent of Du Bois’ talented tenth because he mastered his craft of language and demonstrated the creative and critical thinking skills of a highly educated individual that was capable of inspiring the masses.

According to the African American poet and literary critic, William Stanley Braithwaite, “the two chief qualities in Dunbar’s work are pathos and humor, and in these he expresses the dilemma of soul that characterized the [African American] race between the civil war and the end of the nineteenth century” (Mitchell, pg. 39). Braithwaite furthered his commendation of Dunbar by claiming that “few have equaled Dunbar in this vein of expression—[dialect], and none have deepened it as an expression of Negro life” (Braithwaite, pg. 39). Dunbar essentially supported Du Bois’ claim that literacy and education were important qualities for African Americans to improve their living conditions. Even during the second half of the twentieth century when African American literary critics such as Addison Gayle Jr. criticized Dunbar’s poetry as a striking example of “cultural strangulation” by white elitism (Gayle, pg. 212), others still perceived Dunbar as a living example that “Negro writers could rise to heights of artistic expression” (Redding, 1949/1994).

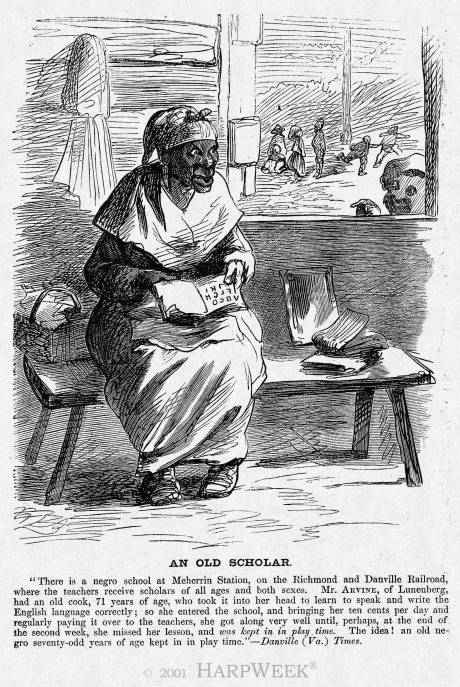

The Power of Literacy and Education

The lessons we could learn from Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Paul Laurence Dunbar about literacy and education are very important because language is a tool that can bridge the gap between conflicting peoples, cultures, or nations. By understanding each other though official languages and by acquiring the creative and critical thinking skills needed to make sound judgements and ideas, people can solve many social issues without resorting to violent revolutions. In the future, one of my goals as an English professor will be to instill the same high value of literacy and education in my students that Frederick Douglass passed down to W.E.B. Du Bois and countless others.

References

Braithwaite, W., (1925/1994). The Negro in American Literature. In Within the circle: An anthology of african american literary criticism from the harlem renaissance to the present. London, UK: Duke University Press.

Gates Jr., H., McKay, N., (1997). The Norton Anthology of African American Literature (1st ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Gayle Jr., A., (1971/1994). Cultural Strangulation: Black Literature and the White Aesthetic. In Within the circle: An anthology of african american literary criticism from the harlem renaissance to the present. London, UK: Duke University Press.

Gilroy, P., (1993). The black atlantic: Modernity and double consciousness. London, UK: Verso.

Macey, D., (2001). Dictionary of critical theory. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Mitchell, A., (1994). Within the circle: An anthology of african american literary criticism from the harlem renaissance to the present. London, UK: Duke University Press.

Redding, J., (1949/1994). American Negro Literature. In Within the circle: An anthology of african american literary criticism from the harlem renaissance to the present. London, UK: Duke University Press.

Sundstrom, R., (2012). Frederick Douglass. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/frederick-douglass/#IntVerEmi

Talented Tenth, (2014). Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/topic/Talented-Tenth

The Frederick Douglass Organization, (2015). Retrieved from http://www.frederickdouglassiv.org/