- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Books & Novels»

- Nonfiction»

- Biographies & Memoirs

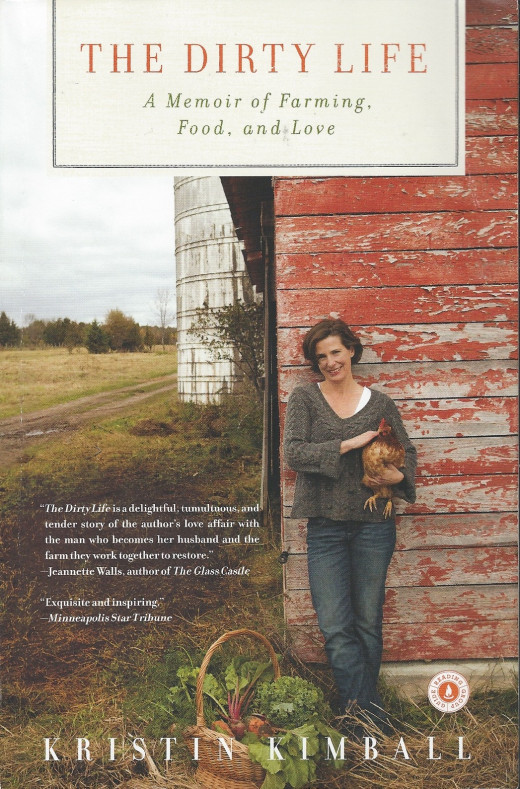

BOOK RECOMMENDATION: The Dirty Life: On Farming, Food, and Love by Kristin Kimball

I tend to only highlight books that I fall head over heels for because I want everyone else to read them and love them too. This book recommendation is no exception.

I COULD NOT PUT THIS BOOK DOWN.

The Dirty Life: On Farming, Food and Love by Kristin Kimball is an hilarious, honest, invigorating memoir of one woman’s epic personal adventure from a NYC apartment where she never cooked to 80 acres of land where she currently runs a FULL-DIET (amazing! meats, dairy, maple syrup, fruit, veggies, grains) CSA program that plans to operate completely fossil-fuel free in a couple years. Her journey is completely connected to a romance that springs up between her and an infectiously crazy farmer. Their story encapsulates in so many ways the homesteading-dreams-turned-real-life adventure that I’ve always been awed by and personally craved. The book brilliantly combines the author’s experiences with love, food, and farming, and I was seriously sad when I read the last page. I wanted the book to go on forever!

Whether you're a farmer or wish to be one in some kind of capacity one day, or if you're just an avid reader looking for a new book to add to your list, I encourage you to pick up and read this book. To compel you, I’ve included some quotes from the memoir that left a strong impression on me or put into words the same feelings and experiences I've encountered while pursuing my own farming adventure.

Quotes from The Dirty Life

On compost:

“Of all the confounding things I encountered that first year, the heat of decomposition – its intensity and duration – was the most surprising, the one that made me want to slap my knee and say, Who knew? That heat comes from the action of hordes of organisms, some so tiny billions can live in a tablespoon of soil. They are in there, eating and multiplying and dying, feeding on and releasing the energy that the larger organisms – the plants and the animals – stored up in their time, energy that came, orginally, from the sun. I think it’s worth it, for wonder’s sake, to stick your hand in a compost pile in winter and be burned by a series of suns that last set the summer before.”

On farm work:

“I was in love with the work, too, despite its over abundance. The world had always seemed disturbingly chaotic to me, my choices too bewildering. I was fundamentally happier, I found my focus on the ground. For the first time, I could clearly see the connection between my actions and the consequences. I knew why I was doing what I was doing and I believed in it. I felt the gap between who I thought I was and how I behaved begin to close, growing slowly closer to authentic.”

On meaning:

“…farming takes root in your and crowds out other endeavors, makes them seem paltry. Your acres become a world. And maybe you realize that it is beyond those acres or in your distant past, back in the realm of TiVo and cubicles, of take-out food and central heat and ar, in that country where discomfort has nearly disappeared, that you were deprived. Deprived of the pleasure of desire, of effort and difficulty and meaningful accomplishment.”

On art:

“A farm is a form of expression, a physical manifestation of the inner life of its farmers. The farm will reveal who you are, whether you like it or not.”

On success and fear:

“In his view, we were already a success, because we were doing something hard and it was something that mattered to us. You don’t measure things like that with words like success or failure, he said. Satisfaction comes from trying hard things and then going on to the next hard thing, regardless of the outcomes. What mattered was whether or not you were moving in a direction you thought was right. This sounded extremely fishy to me. This conversation played out many times, with me anxious, Mark calm, until once, as we sat together reviewing our expenses I was almost in tears. I felt like we were teetering over an abyss. I wasn’t asking him to guarantee that we’d be rich. I just wanted him to reassure me that we’d be solvent, that we’d be, as I put it, okay. Mark laughed. ‘What is the worst thing that could happen?’ he asked. ‘We’re smart and capable people. We live in the richest country in the world. There is food and shelter and kindness to spare. What in the world is there to be afraid of?”

And a lovely quiet moment while making maple syrup:

“I liked running the evaporator. Mark was busy nailing together wooden flats to start our seeds, so it was quiet, solitary work that started two hours before dawn. I had never been a morning person in the city, but on the farm I’d learned to love being outdoors before light. I felt like I was sharing some kind of secret with the unhuman things around me, the birds not yet stirring in the trees, the mud quiet on the ground. I carried provisions to keep up my strength: a French press of ground espresso beans, to be brewed not with water but with boiilng sap for an electrifying drink that had to be sipped in small quantities; also, a dozen eggs and a shaker of salt. Thomas LaFountain had taught me to drop the eggs one by one into the finishing pan, where they would crack with heat and the thickening sap would seep into the cracks and darken and sweeten the hard-boiled eggs, which are fished out with a long spoon and peeled and eaten hot with a heavy sprinkling of salt. I took a plate of pickles, too, an antidote in case I accidently overdosed on sweet.”