Ethnic American Literature: The Heteroglossic and Postmodern

“For postmodernists, the subject is a fragmented being who has no essential core of identity, and is to be regarded as a process in a continual state of dissolution rather than a fixed identity or self that endures unchanged over time”

– Stuart Sim (2001)

To study Ethnic literature is to study the productivity of humankind. By productivity, I am referring to the human capacity to create an immeasurable number of ideas, concepts, or sentences using language. The intriguing aspect of Ethnic-American literature is that author is situated in a unique position of dual-consciousness and biculturalism. The author must experience the tensions, breaks, reconciliations, and rejections of many central aspects of human life: How do I raise my kids? How do I greet you? What am I working for? What should I eat? What should my daily schedule look like? When will I marry? What are the rites of marriage? of adulthood? of birth? Who am I? Everything from the macro-elements of culture, such as political values and structures, to the micro-elements of culture, such as using an alarm-clock or how to set the dinner table, are complicated.

The Grand Narrative

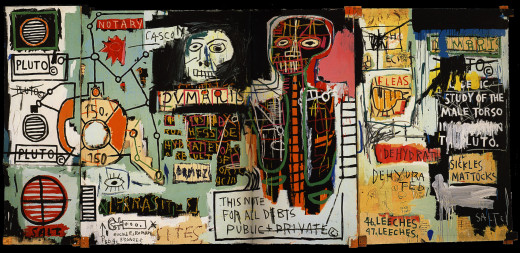

One particular complicated question is: what makes American literature distinctly American is a pluralistic society? The answer to this question has transformed from each time period to the next. The Grand Narrative of American literature, starting from the beginning of the 20th century, is mostly characterized by elitist rule and social Darwinism. The literary canon, or critically and scholarly acclaimed body of literature, was dominated by paternalism; the words “highbrow” and “lowbrow” became critical terms to distinguish the difficult style and form of Modernist literature from outdated naturalist, realist, and other commonplace or bestselling literature. Ultimately, the literary canon was dominated by the works of T.S. Eliot and Samuel Beckett because they infused in their writing an air of literary elitism: specific allusions, difficult metaphors, and very rich symbolism. In effect, the dominant literary figures of the early 20th century in America were mostly highly educated, upper-middle class, and White.

The Rise of Social Activism Post-WWII

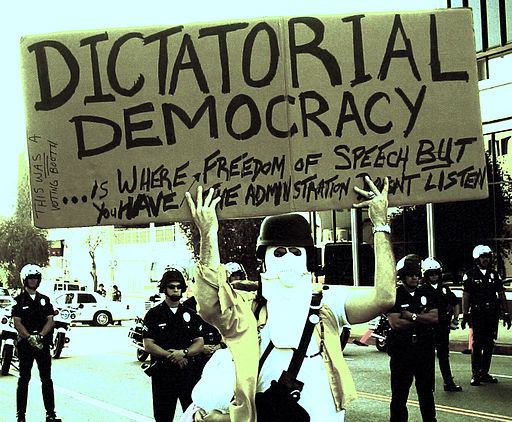

The American literary canon did not dramatically shift until the advent of Postmodernism during the aftermath of World War II. The devastation of global war and massacre effectively shattered the traditional American ideals of liberty, opportunity, equality, and freedom to a greater extent than even after World War I. Thus, the tensions between nationalism and capitalism concerning the politics, economics, and cultures of the rest of the world stirred confusion within the American mindset about the values, ideals, and the realities of living in the “American Democracy.” These uncertainties lead to warring political parties during the 1960s, which ultimately paved the road for many social movements such as the Black Arts Movement, the Native American Literary Renaissance, The Chicano Movement, and Feminism to rise into the socio-political and scholarly spotlight.

The special challenges these social groups faces were, are still are, multifaceted and intricately connected with the politics, economics of the United States. Among these challenges, although each group has their own specific manifestations, include: the conformity with and assimilation into mainstream culture, self-identity issues, biculturalism, and dual-consciousness. Oftentimes these groups experienced or are still experiencing a bracketing of otherness or nonperson. This means that they feel excluded, different, alien, or innately inferior to those surrounding them. Ralph Ellison’s narrator in his novel “Invisible Man” is a prime example of the African American construct of self and social identity as either an Other or nonperson during the early 20th century in the South.

Heteroglossia

The influx of various and contradictory voices (heteroglossia) highlighted many existing tensions within American society and the construction of the literary canon that had otherwise remained silent. Aspects of American colonialization, industrialization, and globalization were openly questioned and investigated; the idealisms of American democracy were challenged by the Other: the discriminated, the exploited, and the nonpersons of society; the constructions of self-identity and social-identity were reworked and revised to account for stereotypes, cultural transformations, sexuality, class, gender, the unconscious, and a myriad of other critical approaches. Ethnic literature in particular was, and still is, viewed through a pluralistic critical lens in which the historical and socio-political elements of a literary work or author are mostly culturally relative, meaning that all Ethnic authors define literature in their own culturally specific response. Ultimately, as the United States entered the Postmodern Age, the literary canon war had effectively begun.

Embracing a Dialogic Worldview

While American feminists from 1970-present are fighting to rediscover silenced female authors from older time periods, seek out to reinterpret “classics” in the literary canon according to a feminist point-of-view, and essentially alter the literary canon justly, so too are many advocates of cultural studies pursuing ethnic authors and literature to rebuild and reinterpret what it means to be an American writer. While no two ethnic American writers can agree that there is a distinctly American literature, they may agree that to be American is to be pluralistic. In other words, to be American today, one must embrace the diversity and uncertainty associated with engaging new influences and perspectives offered by ethnic authors.

Understanding the "I" through the Other

This constantly changing vision of the American literary canon allows room for ethnic diversity and multiculturalism to lay a stake next to the names of Walt Whitman or Mark Twain in American literature anthologies. Although the vision is difficult – to be American is to embrace everything that is not American because that is the only way to achieve a truly democracy and equal understanding of everyone’s particular voice, culture, and worldview— it is nevertheless something that is exciting for both American readers and writers.

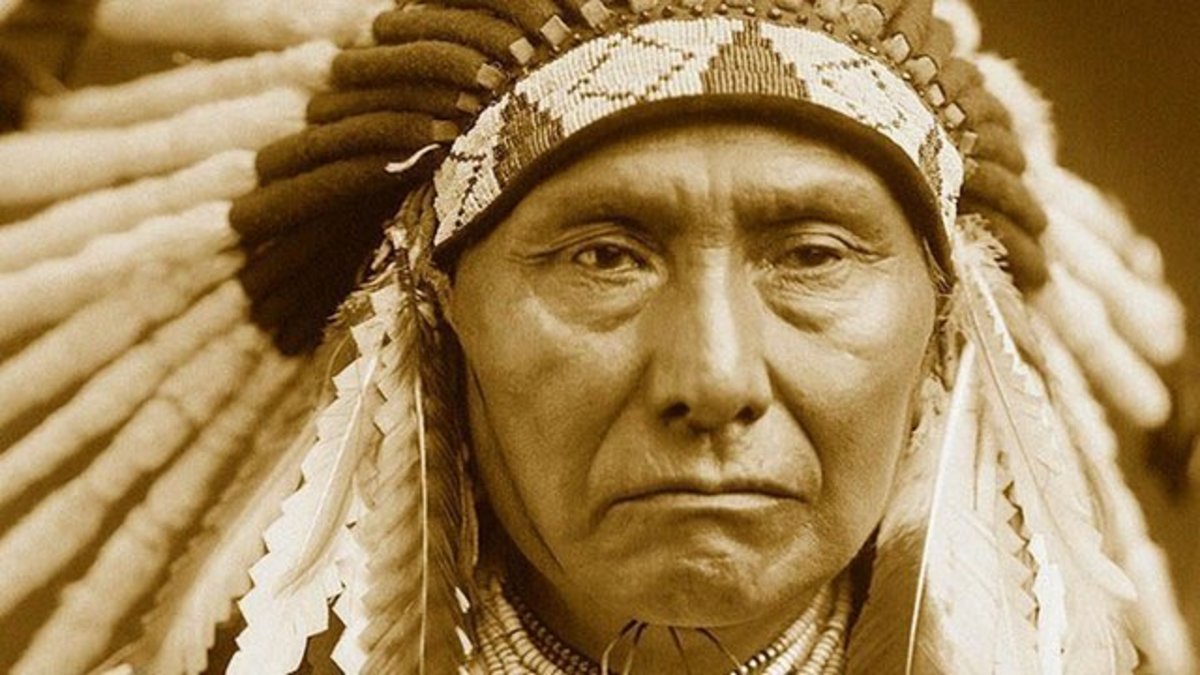

Furthermore, there is no better critique of American culture, society, politics, and economics than the literature written ethnic American authors. Readers can learn about foreign perspectives on the structures that govern everyday life in the U.S. while also taking a trip abroad and learning about the way of life in other cultures. Oftentimes in ethnic American literature, American ideals are portrayed in a new light. For example, in Hispanic-American literature the idea of “Home” is brutally inverted into “Homelessness”; the Native-American ideal of community and spirituality is pitted against the Western ideals of property, and owning and cultivating land; Asian American writers often express the differences between American and Asian cuisine and clothing.

Concluding Thoughts

By studying ethnic American literature is to study the diversity of human thought and perspective. It is incredible that one species can live and thrive following so many different sets of values, beliefs, traditions, customs, and cultures and manifest those in thousands of different languages across the globe, of which are equally complex as the next. When an author adopts a new language and masters it enough to speak and write fluently, their writing represents aspects of their old and new life ambivalently and then readers have unique access into worldviews so foreign, so original, so intriguing...