Andrew Weaver's "Keeping Our Cool": A Summary Review

Dr. Andrew Weaver’s book, Keeping Our Cool , is an easy book to like, but a hard one to summarize. It’s easy to like because it conveys a sense of Dr. Weaver’s personality, interweaving personal experiences, reactions and viewpoints with the science (and policy issues!) of climate change. It’s tough to summarize for pretty the same reason—but more on that later.

Dr. Weaver is an interesting character. That he is a distinguished scientist is not surprising—he is one of the leading scientists involved in climate modeling in Canada, a professor at the University of Victoria, and a lead author on three of the IPCC Assessment Reports—but his outspokenness and effectiveness as a communicator is perhaps a little more unexpected. His own words in Keeping Our Cool reveal him to be careful in his judgments and diction, yet passionately committed to the science he explains—and to communicating the consequences that have already flowed, and yet may flow, from the realities the science tries to discern.

Dr. Weaver’s conviction and confidence are also revealed in an ongoing legal drama. He is (with Dr. Rajendra Pachauri and Dr. Simon Lewis) one of only a very few scientists who have sought legal remedies for lies told about them—I suppose, as the matter is still before the courts, I should have said “allegedly told about them”—by climate change denialists in mainstream media. In his case, according to Dr. Weaver, he was libeled by four articles published in the Canadian paper the National Post between December 2009 and February 2009. In his own words,

I asked the National Post to do the right thing, to retract a number of recent articles that attributed to me statements I never made, accused me of things I never did, and attacked me for views I never held. To my absolute astonishment, the newspaper refused.

Lawsuits are not to be embarked upon lightly—especially in Canada, where frivolous suits are routinely punished by judgments which require the loser to pay all court costs, including the winner’s. (Not coincidentally, a similar system prevails in Britain, where Dr. Pachauri’s suit was settled out of court in his favor. The newspaper pulled the libelous article and posted a full retraction—and paid a rumored six-figure settlement. I suppose I should add that Dr. Lewis’s complaint—he did not sue, but made a formal submission to the UK Press Complaints Commission---ended similarly, with the Sunday Times apologizing and retracting their original article, which had falsified Dr. Lewis’s views.)

So what does Dr. Weaver tell us in Keeping Our Cool? Well, telling you that is where difficulties begin for the conscientious reviewer. It's easy to say that one characteristic is its distinctly Canadian perspective: the subtitle, after all, is "Canada In A Warming World." That perspective will be attractive for Canadian readers, but also to those interested in how the politics of climate change play out in a jurisdiction a little less well-covered than, say, Washington, DC.

Perhaps the most valuable aspect of the book, though, is its first-person account of a top climate scientist experiencing significant weather and climate events, the social and media reactions to them, and especially the pressure-cooker process of creating an IPCC report. But doing so seamlessly—which I take to be the aspiration here—means writing in rapid succession from the perspectives of human being, of family man, of citizen, of scientist and of scientific writer. That’s a lot of “hats” for Dr. Weaver to wear in a single narrative, and a lot of information for readers to sort out. I’ve already mentioned the advantages, but there is of course an organizational downside too: in a word, it’s not so easy to say just what each of the six chapters of Keeping Our Cool is “about.” However, summoning up an echo of Dr. Weaver’s courage, I’ll try.

The sizeable Introduction focuses mostly upon the personal experiences with weather and media in 2007. In 2007 Victoria, British Columbia, Dr. Weaver’s home base, experienced some very unusual weather—a “horribly wet and dreary” winter, followed, as it turned out, by more of the same in July and August. In between, Weaver spent a month in Greece, where fires reached what the Vancouver Sun termed “biblical proportions,” before the late summer brought rainfall enough to supplant drought with flooding.

Weaver struggled to craft his response to the media; he knew that on the one hand, it is not scientifically justifiable to attribute any one weather event, but that on the other hand it is also true that climate change “loads the dice” for the occurrence of such extremes. (Indeed, in 2004 Dr. Weaver had co-authored a paper showing that Canadian wildfires burned increasingly wider areas over the span from 1959 to 1999 in association with increased temperatures and atmospheric CO2 concentrations.) His response:

1) You would expect an increased likelihood of such forest fire events because of global warming, so 2) Get used to it, since, in the words of rocker Randy Bachman, 3) You ain’t seen nothing yet.

This summer has, of course, seen a parallel event in Russia, where the wildfires and heat have reportedly cost more than 11,000 lives and 15 billion dollars US. In 2007, 68 fatalities were reported, with economic losses of about 2 billion; it seems that Dr. Weaver was prescient in quoting Mr. Bachman.

The discussion of the challenges of attributing specific events to climate change is very clear. It is also very helpful in appreciating the difficulties faced by Dr. Weaver and his scientific colleagues in commenting accurately on the matters. Also discussed very frankly were the issues around air travel and carbon offsetting—Dr. Weaver was uncomfortably aware of the carbon footprint generated by his family’s vacation to Greece.

Chapter One, “Global Warming In The News,” continues somewhat in the same vein, with Weaver’s media experiences with a biased talk radio host, and debating climate change with prominent climate change skeptic Dr. Richard Lindzen—and with charmingly “geeky” graphs of newspaper coverage! Dr. Weaver examines the problems of biasing due to the journalistic ethic of “balance”, of lack of understanding of scientific method, and of scientific uncertainty.

Finally, consideration is given the “Astroturf” brigade which has grown up to oppose the mainstream scientific view on climate change, and the shift toward greater public acceptance of the importance of the issue that occurred in 2007—a shift that seems to have been partially rolled back in 2010 by denialists, such as those challenged by Drs. Weaver, Pachauri, and Lewis. (For more on the public relations war around climate change, see my review of James Hoggan’s Climate Coverup, linked below.)

- "Climate Cover-Up": A Review

"You've been lied to. The first decade of the new millennium has been the warmest ever--yet you are being told that the world is cooling. The greenhouse effect was discovered in 1824..."

Chapter Two, “A Passage Through Time,” turns more decisively toward the scientific background, with an excellent summary of the early science of climate change, from the early research of Joseph Fourier onward, and the shift into official concern about the effects of climate change expressed with the National Academy of Science and Environmental Protection Agency reports of the 1983. Weaver quotes the conclusion of the latter that:

. . .changes by the end of the 21st century could be catastrophic taken in the context of today’s world. A soberness and a sense of urgency underlie our response to a greenhouse warming.

Dr. Weaver does not mention the response by President Reagan’s science advisor, George A. Keyworth II, who surprised no-one then or now by calling the report “unnecessarily alarmist.” He does, however, continue with a summary of the development of the International Panel on Climate Change, and a vivid account of his experiences as lead writer for the Fourth Assessment Report, which came out in February of 2007.

Work on the Report began in 2003 with “scoping meetings,” but Dr. Weaver (and his 13 co-authors on what would be Chapter 10) started with the first lead author’s meeting in September of 2004. The “zeroth order draft” was due January 14th, 2005; there were 78 contributing authors. 23 pages, containing 123 peer comments then duly arrived on April 29, just two weeks ahead of the second lead authors’ meeting; and the formal first draft was due August 12. Peer review of that draft provided a break before Weaver received what he calls “the birthday gift from hell”: “172 pages outlining 1331 reviewer comments, concerns, and criticisms.”

Ouch! Weaver comments:

Rookie authors were shell-shocked; veterans were dumbfounded. As lead authors, we had to respond to each comment and indicate how we modified the text to account for the issues raised.

December brought another lead author’s meeting; the second draft was due in March 2006. The expanded group of reviewers for the second peer review luckily seemed a trifle less picky, coincidentally producing the same 1331 comments, albeit in 173 pages this time. Ten days to process that. Blessedly, following more “meetings, discussions, arguments, late nights, and writing,” the final draft was submitted September 12, 2006.

Some folks have the idea that climate scientists are promulgating “alarmism” about climate change in order to “keep the grant money coming”—as if grant money went straight into researchers’ pockets. Elsewhere in Keeping Our Cool Dr. Weaver points out that it would be more logical, if that were really the case, for scientists to insist that the matter needs more study. But those holding such opinions may want to ponder the fact that the process Weaver describes was undertaken on a volunteer basis. IPCC authors receive no pay for their work. Presumably they get to fly to meetings on the IPCC dime, but they have to spend all their time in generic conference centers butting heads with their colleagues--not the most efficient way to get wealthy.

Dr. Weaver concludes the Chapter, inevitably, with his account of the news of October 12, 2007:

. . . a barrage of emails and pone calls hit, asking for interviews about the announcement that the IPCC was a co-recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize. I was stunned. Sure enough, minutes later I received emails from Susan Soloman, chair of Working Group I, and Rajendra Pachauri, the chair of the IPCC, congratulating us all. It was a most wonderful end to a process that had taken up enormous amounts of my time over the last two decades.

(Consulting Google, though, I find that it isn’t really the end; Dr. Weaver will be back in the saddle again as a lead author on Chapter 12 of Assessment Report 5. By the way, one of the false statements about Dr. Weaver in the National Post was a claim that he was distancing himself from the IPCC.)

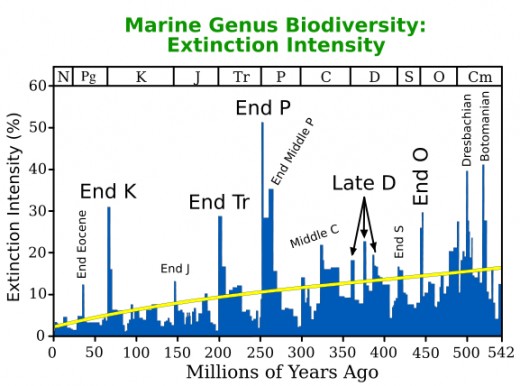

Chapter Three is entitled “The Nature Of Things,” and tackles ancient climates and the methods for their study, ancient extinctions, ocean chemistry, the Ice Ages and rapid geological shifts called “Bond cycles,” which show that Earth’s climate system is capable of relatively rapid shifts.

That last part is less arcane than it may sound, since climate change deniers often argue that “climate change has always occurred” as if it were news—but fail to realize the implication of that argument is that climate stability can’t be assumed in the face of human interference, either. Again, Weaver’s exposition is excellent, characterized by straightforward declarative sentences marshaled into crisp, readable paragraphs.

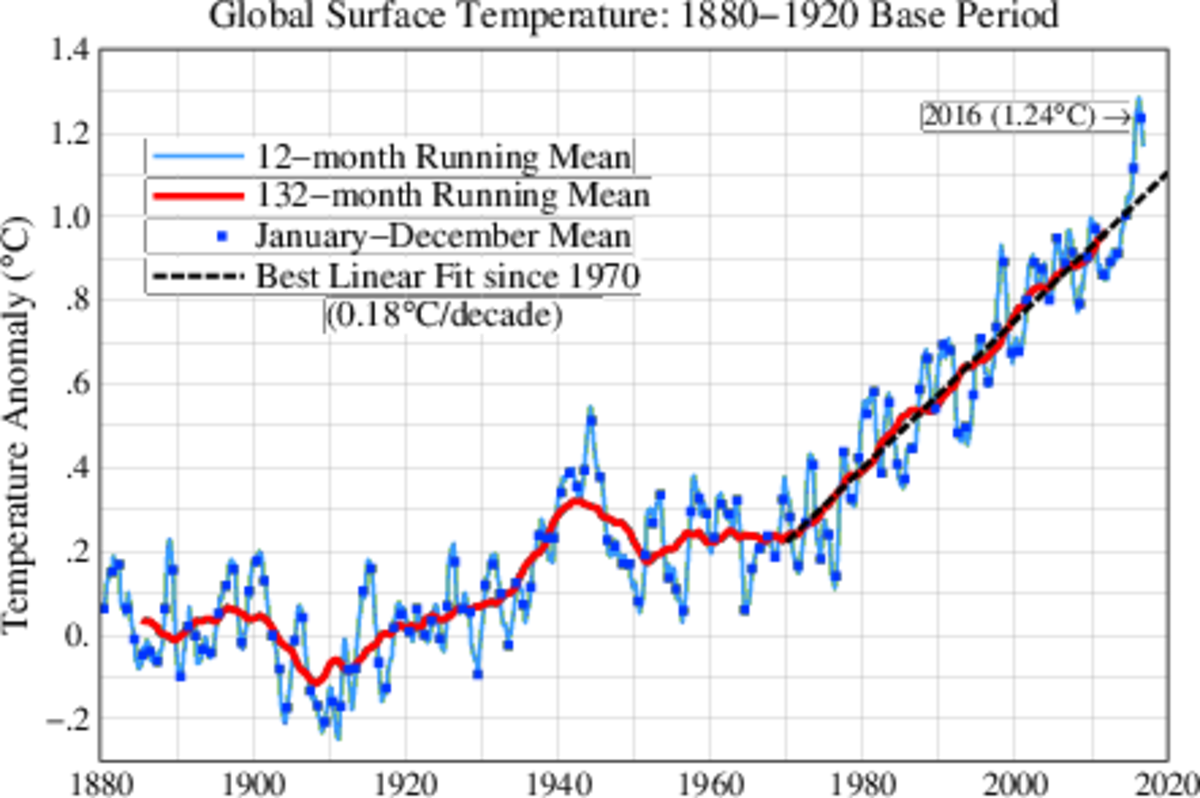

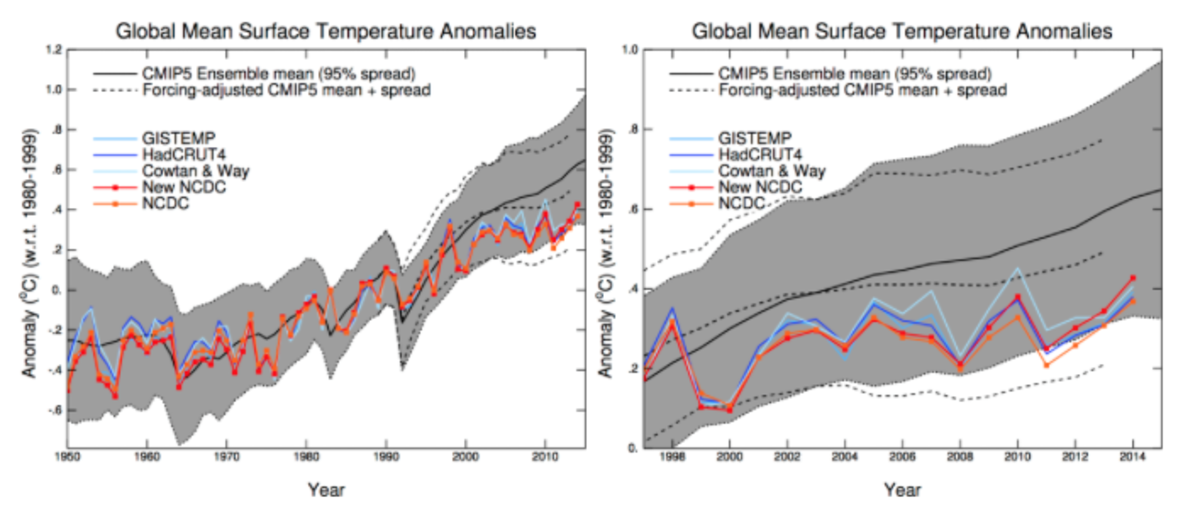

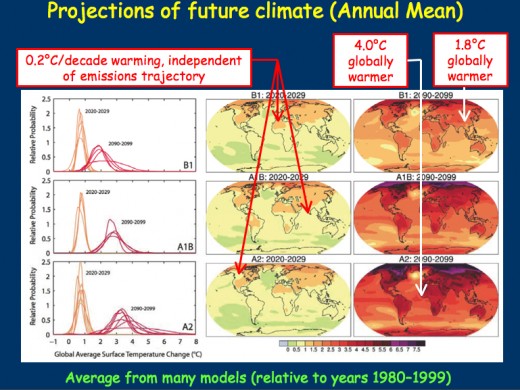

Chapter Four takes up “The Human Footprint.” The subject matter encompasses both attributional questions--as in the passage debunking attempts to pin warming on solar variations or that describing how the characteristic spatial patterns of the warming we have observed so far are convincingly captured in model climate simulations—and questions regarding the consequences of warming.

Among the latter, Weaver mentions:

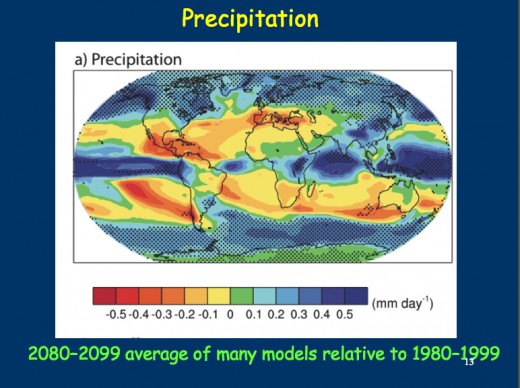

- Detrimental precipitation changes leading to a paradoxical increase in both flooding and drought;

- Changes in hurricane intensity and a shifting of storm tracks—the latter has been observed in the 2009 and 2010 storm seasons, with hurricanes developing in previously hurricane-free regions;

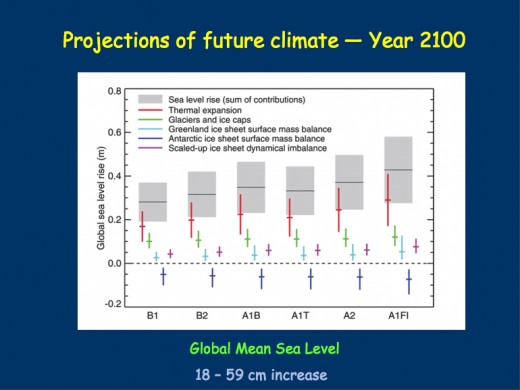

- Sea level rise;

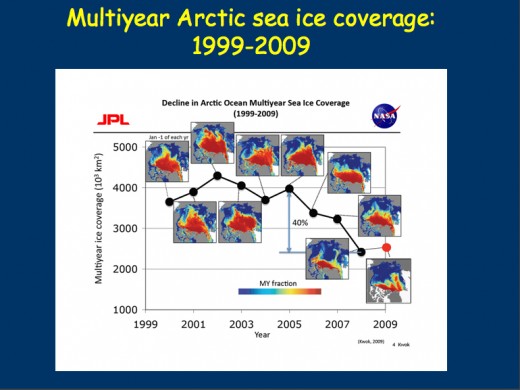

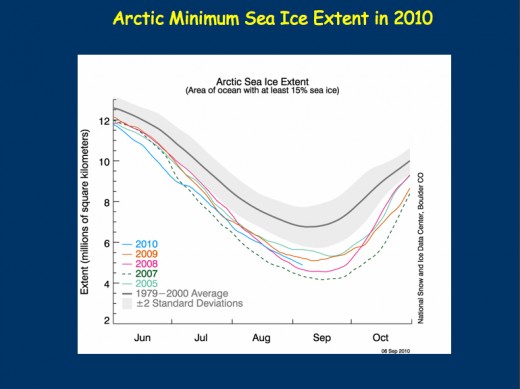

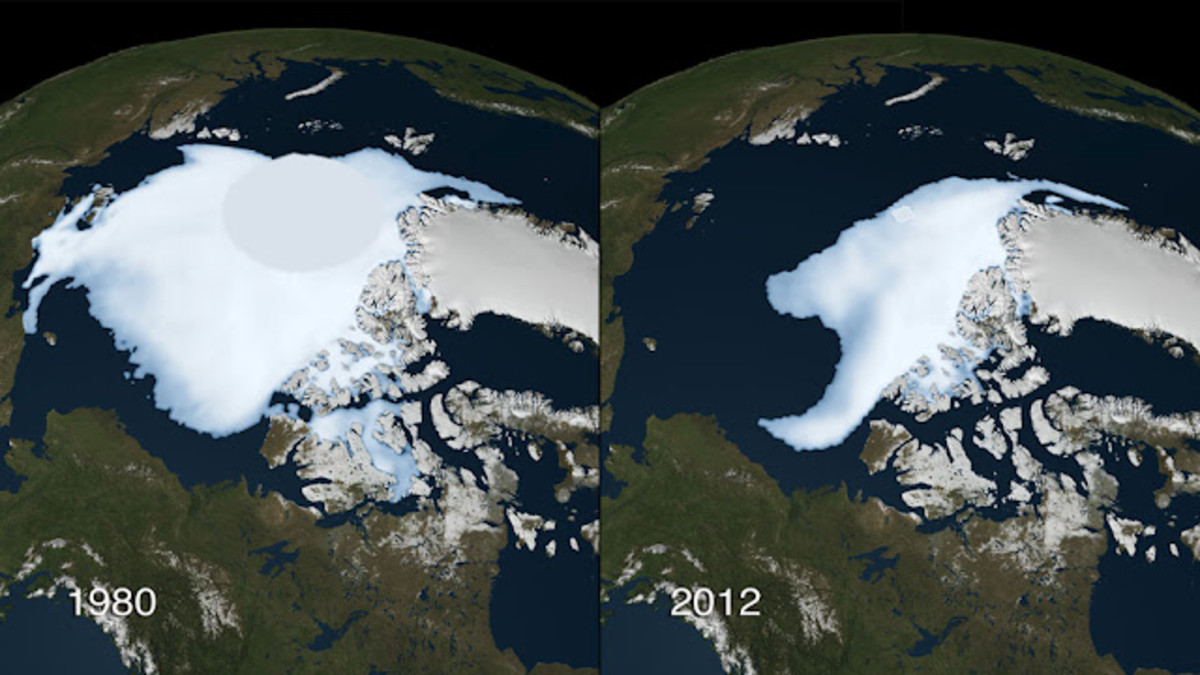

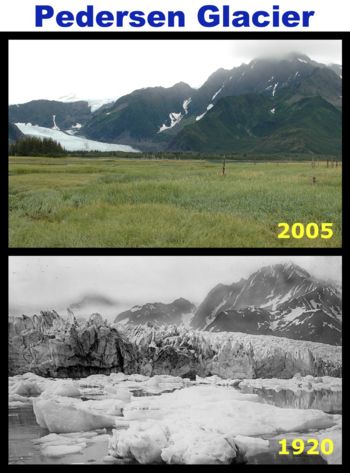

- Loss of Arctic sea ice;

- Melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets.

Though the prose continues to be crisp, the organization here becomes a little more cyclical, as discussions of climate research in Canada and an expanded discussion of detection and attribution studies alludes to topics previously broached in the book.

Also significant is an excellent account of how climate models are actually built and evaluated. Here again Dr. Weaver’s personal expertise really shines through. Given the erroneous impression still shared by many that climate modeling is an affair essentially statistical in nature, it's worth highlighting that the models simulate actual physics:

“The climate model was not constrained [except] by solving the mathematical equations [representing physical processes.]”

In Chapter Four, as throughout the book, there are some really well-designed graphics. But I suspect that they look much better in the hard-cover version than in the paperback edition that I purchased; the paperback's small size and low contrast makes them much less effective than they could be. (No freebie “review copies” supplied for this article!)

Chapter Five continues to interweave policy and science in a somewhat elliptical way under the title “Turbulent Times.” Some of the facts and views in this chapter are as shocking as anything you’ll hear about on this topic—for example:

“In fact, the projected rate of change in the temperature of the nest 2 centuries has no analogue in at least the last 50 million years. . .” (p. 208)

“We’re going to get a meter [of sea-level rise] and there’s nothing we can do about it. . . It’s going to happen no matter what—the question is when.” (p. 215)

“. . .by the end of the 21st century [the “20-year-return” precipitation event under emission scenario A1B] will occur once every 8.6 years.” (p. 217)

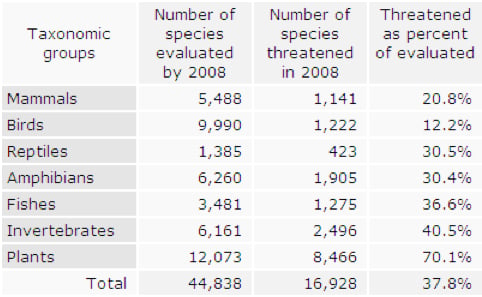

“And if global temperatures exceed about 3.3C warming beyond today’s temperatures (about 4.0 C above pre-industrial values), the best estimate is that between 40% and 70% of the world’s species become extinct.” (p. 218)

In reading these quotes, it's worth remembering that Dr. Weaver describes himself as "a born optimist."

Dr. Weaver frames this information in the context of basic ethics: if we would condemn anyone who tossed dangerous waste onto his neighbor’s property and used force to prevent the neighbor from doing anything about it, we would find it a shocking, criminal act. Why, then, do we tolerate treatment of the atmosphere we all share which amounts to much the same thing?

He concludes the chapter with an extended exposition of emission reduction targets, including the “carbon allotment”—since it isn’t so much the rate of emissions that matters as it is the total amount emitted:

So if society accepts that the 2 C threshold is the upper bound of acceptable global warming, we have 484 billion tonnes of allowable carbon emissions to play with starting January 1, 2007, until the day we finally arrive at zero emissions. And for each year we dither about deciding what to do, we lose 10 billion tonnes, at current emission rates, of our future carbon allotment.

Presumably, we are now working on an allowance of around 450 billion tonnes of carbon. (If that seems somehow numerically out of kilter, you may be thinking of emissions of CO2—they are much higher than emissions of “carbon,” since the CO2 molecule includes two oxygen atoms (atomic weight circa 16) for each carbon atom (atomic weight about 12.))

The final chapter, “Investing In The Future,” is probably the most discursive of all. It begins with ethical issues, particularly the question of intergenerational equity—it’s an irony that those most concerned not to leave their children burdened with financial debts too often seem unconcerned with potentially crushing “environmental debts.” Weaver then presents the idea of “contraction and convergence,” which he describes as “an equitable framework for allocating carbon emissions as we move toward carbon neutrality.”

A brief consideration of “emissions-free” energy options follows; the “options” comprise nuclear energy, renewable energy sources—the drawbacks of which are honestly set forth—and so-called “clean coal” technology, regarding which Dr. Weaver is, if I read him rightly, dubious but not dismissive.

Considerations of various social policies follow: price signals (a category comprising both cap-and-trade schemes and carbon taxes), the challenge of the car, unreasoning resistance to potentially beneficial change. High on the list of entities exhibiting the latter is the Federal government of Canada, whose chronic obstructionism in climate negotiations Dr. Weaver decries. He is particularly scathing in describing the events around the 2007 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Uganda, which ended up adopting “aspirational targets”:

I have no idea what “aspirational targets” are. It strikes me that this political mumbo-jumbo translates into “targets we have no intention of meeting.”

Unfortunately, this assessment is hard to rebut.

Weaver contrasts this governmental bad faith with a couple of 2007 statements from Canadian and international CEOs of notable corporations, couched in much tougher language, calling for meaningful action on emissions mitigation. He concludes by leaving no doubt that one on the things he sees threatened by climate change is democracy itself:

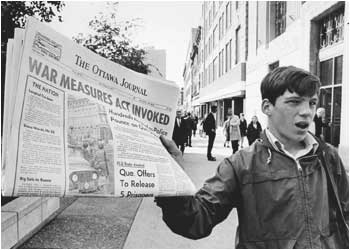

If we reach the stage of crisis management, I can’t see how our western democracies will survive unless we move toward a War Measures Act or despot style of governance with centralized power in the hands of a few. I doubt many of us would want to head down that path.

There is an Epilog to Keeping Our Cool. In it, Dr. Weaver speaks with pride and optimism about the adoption by his Provincial government, the government of British Columbia, of a revenue-neutral carbon tax in the 2008 budget. The tax began by taxing carbon at $10 a tonne, rising each year by $5. By law, the revenues are returned to the people of BC by corresponding reductions in other taxes; protections for lower-income citizens were included.

As of this writing, the tax is still in force, though the Liberal government that proposed it looks more than a little shaky; its fate should a New Democrat regime take power is unclear, as the New Democrats are considered pro-environment, yet their leader has spoken unfavorably about the measure. So far—and contrary to Dr. Weaver’s expressed anticipations—no other jurisdiction has followed BC’s lead.

Yet the last sentence of Keeping Our Cool is certainly no less true than when Dr. Weaver wrote it:

The time to deal with global warming is now.

Doc Snow: The Beginnings Of Climate Science

- Global Warming Science In The Age Of Napoleon: Jose...

Joseph Fourier first inferred the existence of a greenhouse effect in 1828. This is his story. "If we think of Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, many things might come to mind. . ." - Global Warming Science In The Age of Revolution: Cl...

Claude Pouillet played an important part in early climate science, by measuring the sun's radiant energy--the "solar constant." 'A forest of bayonets,' thought Claude Servais Mathias Pouillet, Professor of Physics at the Sorbonne..." - Global Warming Science In The Age Of Queen Victoria:...

John Tyndall first identified the main greenhouse gases in 1860. This is his story. "Perhaps its the dramatic weather changes, or perhaps it is mere coincidence, but mountains recur..." - Global Warming Science And The Dawn Of Flight: Svan...

Svante Arrhenius calculated the first mathematical model of global warming via CO2 in 1896--by hand. This is his story, and the story of the observer whose data he used. - Global Warming Science, Press, And Storms: Nils Ekh...

Nils Ekholm, scientist and self-made man, provided probably the clearest picture of climate science in 1900. "Scientists are expected to live and die on the quality and integrity of their data analysisbut usually that is a metaphor..." - Global Warming Science And The Wars: Guy Callendar

In 1938, the science of CO2 and climate was a sleepy backwater. Guy Callendar singlehandedly brought it into the modern era--in his spare time. "Nearly everybody likes to be right, and scientists perhaps more so than the rest of us..."

Other Related Hubs by Doc Snow

- Through A Glass Darkly: Equinox Reflections, 2010

A brief memoir of watching the 2010 sea ice melt--and what it may mean. "Its just past the fall equinox, that day when the year turns from light to dark, summer to winter. Days have been growing shorter..." - "Crystal Waters": A Meditation

Not all environmental disasters are due to global warming; some are part of the cause. "I might not finish this piece tonight. Its hot, really hot, and the wind is rising outside with the rising storm. Theres a squall line of sorts on the way..."