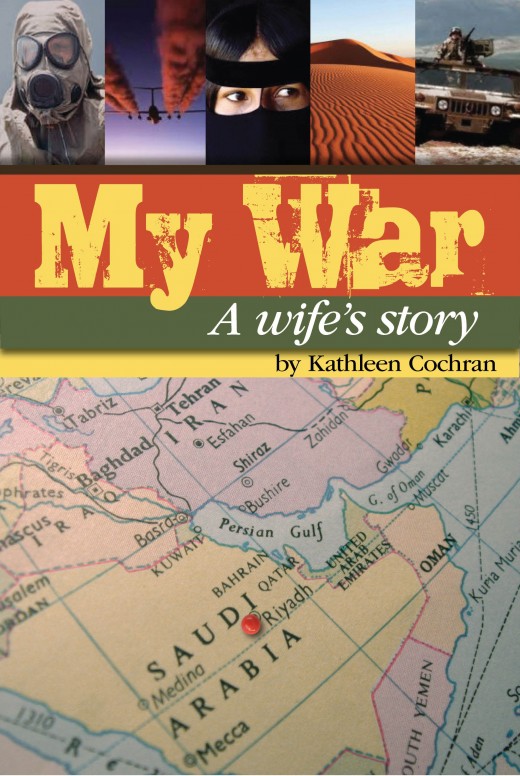

My War - A wife's story (an excerpt)

Chapter One

They say you should write what you know. So I'll start with that and add what I didn't know later.

I know I was standing on the sidewalk in front of my villa in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, at about ten o'clock the night of January 21, 1991. I know I was holding the hands of my three children who were still in their pajamas. How I was holding three hands with my two I don't remember. But mothers do such things, especially when their children are having SCUD missiles shot at them.

I know I heard three pops, like balloons bursting right next to my ear. Along with each “POP!” was a Ping-Pong ball of light streaking up from the southern rooftops into the night's sky over our heads. “POP! POP! POP!”

I know that I knew enough to get my children across the main street of our compound to the childcare center on the other side where a tent was set up inside. It was really a field hospital tent from the U.S. Army. But it was provided to our compound of American military families to protect those of our children who were too small to fit into their gas masks. Two of my three were too small: my five-year old, Jesse, because he was only a five-year old and my ten-year old, Bethany, because she was

so petite the thing wouldn't seal against her slight neck and throat. My eight-year old, Jordan, fit into his just fine, so he was along because I didn’t want to leave him alone in our villa until I got back. He and I would return to our villa, get in our gas masks, and wait in my bedroom closet for the “all clear.”

If you were worried about bombs, you went to the lowest part of your house, a basement if you had one. We didn't. Nobody had basements in the desert. If you were worried about chemicals, and based on Saddam Hussein's reputation we were, you went to the highest place in your house that had no windows or exterior doors. For us, that was the walk-in closet in my bedroom, which was almost in the dead center of the villa.

That was the drill. That was how I was trained in the past few days. Hearing the “POPs” - I froze. This was the part I was not trained for.

There were lots of other people running with their children for the daycare center. Army families are young because nine out of ten people in the Army are under the age of forty. Army posts all over the world are populated by young families with plenty of little kids. So was ours, and all those little kids were out of their beds and out in the street because the sirens had gone off indicating we were under attack. These were little ones who shouldn't have to worry about fitting into a gas mask at this point in their lives. But here they were, all in their PJs just like my kids, out in the street in the middle of the night, wondering what kind of fun game this was.

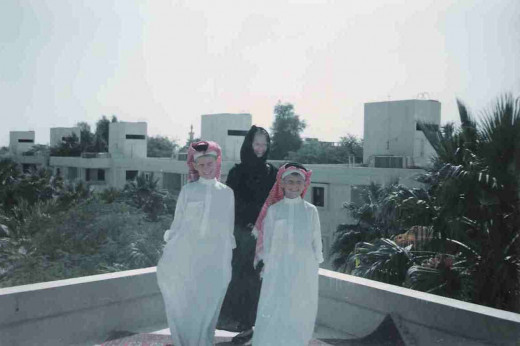

Our compound was laid out on kind of a double H-shaped grid. One H was set perpendicular to the other H. Our villa was the first one inside the gate, right next to the supply warehouse, which was opposite the villa used as the daycare center. There were about six villas on both sides of each leg of the first H. They were all exactly alike on this side of the neighborhood. They were two story houses, known succinctly as “the two- stories.”

Each one had an exterior of white stucco on all sides and had wide porches two-thirds of the way across the front of the villa on both levels. A tiled set of stairs led from the parking space on the side of the villa up to the front porch, which was also covered with large square beige tiles. The homes had well-manicured but small front yards lined with desert-hearty shrubs and Egyptian rosebushes. In the back of the houses on our side of the street there was a tree-lined, grassy, common area about the width of three picnic tables set end to end. The villas on the other side of the street had individual small back yards comparable to their front yards.

Those of us who lived in the two-stories were instructed to take our too-small-for-the-gas-mask children to the daycare center by the front gate. Families living in villas on the second H of the compound took their little kids to the recreation center where another medical tent was set up. With children under the age of six in almost every household, that translated into almost every family on the compound having at least two members out running through the streets in the dark of the night. Most families were in the same situation I was: the wife was home alone with the children because the husband was downrange or with their unit here in the Riyadh area. Only by the luck of the draw did a wife have her husband home that night, like my next-door neighbors, the Taylor’s.

All those running parents and children froze in their tracks at the sound of the “Pops” just like I had. It was right about then I heard Major Taylor holler to his children, three little girls who were about the ages of my kids, “It's OK. It's the Patriots. That's what we want to hear. Keep going.”

Yeah – the Patriots: American technology's equivalent to a security blanket for all of us. Our compound was in the footprint for coverage by the Patriot missiles because of our proximity to the airfield. Good for us.

But wait a minute. Patriot missiles intercept SCUD missiles by breaking them apart. Then the pieces of the SCUD fall out of the sky. My children are right under those falling pieces . . . not good. Yeah. Keep running.

I checked Bethany and Jesse safely into the center where they would sit in “The Bubble,” as we came to call it. They would pass the time playing with the paper fans that my daughter made for all of the other children out of construction paper, partly because it was hot in the Bubble, partly because it was the only thing readily available in the daycare center, and primarily because Bethany was resourceful. This first night of SCUDS the children had no way of knowing how long they would be in there. Nobody did.

The air conditioning was turned off as per SOP, standard operating procedure. There might be chemicals in the air and air conditioning would suck them into the building. We were all instructed to turn off the A/C in our villas as soon as we heard the sirens. There were monitors on the compound that were supposed to emit a different kind of siren if chemicals were detected, but nobody was going to put all their faith in those monitors when it was your very own children whose lives were at stake. So we turned off our A/C as we’d been instructed.

Thank God the kids were calm considering they were awakened in what was the middle of their night, and put through the drill we had assured them was only a drill and would never really happen. Well, hell, that's what they had told me too. How else do you think they could have gotten me to come to Saudi Freakin’ Arabia in September of 1990 with my three babies?

Maybe I should start at the beginning. Well, not exactly the beginning but let me back up a little.

***

In the winter of 1990 my husband, Mike, and I were looking at options for our next Army assignment. We just spent four years at Fort Lewis, Washington – no doubt the best four years of our fifteen-year marriage. But it was time for a PCS – a permanent change of station.

Fort Lewis was beautiful. Washington State was beautiful. The Pacific Northwest was beautiful. And after four years enjoying this beauty, the best option available to us was to be reassigned to the most severe desert on the planet. Our other choices included Seoul, Korea, where the kids and I would live while Mike spent Monday through Friday each week downrange with his Infantry brigade. He would come home on weekends. Yeah. Sure. I wasn’t an Army wife with fifteen years’ experience for nothing, and I wasn’t going to fall for that. I knew full well the kids and I would get a two year look at Seoul, up close and personal, and we would be lucky to see my husband and their father one weekend out four each month.

We were due for an unaccompanied tour, a year of separation when Mike would go somewhere overseas and leave his family behind. Unaccompanied. Well, it was time. We'd never had one. Mike’s career as a professional soldier spanned the years 1976 to 1990 up to that point. It had been a period of relative peace following the ten years of Vietnam. It was a great time to be married to a soldier if you were the wife. It was not such a good time to be a soldier if you were Infantry, Airborne, Ranger, Pathfinder - never mind the rest.

Mike spent the previous summer deploying a brigade to fight the fires in Yellowstone and providing them with beans and boots, but no bullets. He said it was the closest he figured he would ever come to real combat conditions. “Be careful what you wish for . . .” Who’d a thought a year later he'd be kissing his wife goodbye in the morning and saying, “Bye honey, I'm off to the war. See you tonight.”

As we looked at our options in the spring of 1990, a major general (a two star) Mike worked for briefly here at Lewis called him into his office to recount his family's wonderful experience accepting an assignment just a year or two earlier in Saudi Arabia. “The best kept secret in the Army,” he said and he was right – at the time. The general called it “Club Med” as PCS moves went in the 1980s.

It was a two-year overseas assignment as opposed to the three-year standard timeframe for living in the U.S. This was significant because, based on my previous experience; I thought living in a country other than America had a shelf life of about thirty months. Those last six months were pretty miserable as I remembered our tour of duty in Germany in the early 1980s. Of course I was alone most of the time in the first half of the assignment with my one year-old. During the second half, I was alone most of the time with a newborn and a three year-old, and no American television for company during those lonely nights. I know that sounds very trite, but when you don’t have something that essentially says, “OK, I might not be home, but at least I feel connected to home,” you feel the absence.

Still, there were some benefits. During those Germany years, my daughter’s imagination developed in ways I couldn't imagine at the time. It probably turned out to be the best opportunity to thrive I could ever have given her. I have no doubt it was the reason she found she had a gift for languages later in life, became an avid reader, and was always capable of finding her own amusement without the need of anyone's company but her own. As an Army Brat until the age of fifteen, these traits would be of great use to her for the rest of her life.

Surely there would be unknown benefits to this assignment as well. In fact, there were some obvious benefits right off the bat. An assignment to Saudi came with the promise of great housing, which meant a great deal to me after pouring my heart into six houses already just to pick up and leave them for the next PCS.

I was looking at just one more temporary home for my family before we retired to our hometown in Georgia, and I finally got my hands on a house that I would actually get to keep. After three civilian houses and three sets of quarters in five moves, I no longer had the emotional energy it took to repaint and re-wallpaper a newly-purchased house in a new town or transform the cinderblock walls and mismatched linoleum floors of Army quarters into something resembling a home. I just didn't have the heart left to pour myself into the effort it took to make something worthy of House Beautiful one more time out of what I had packed in my moving boxes, then in a few years walk away and leave it behind.

The Saudis would provide us with a furnished, five bedroom, and three full baths, spacious and elegant home that they referred to as a “villa.” I only had to add pictures for the walls, lamps for the tables, kitchenware, and my own sheets and towels. Then in just two short years, I'd get my very own house for our final assignment before retirement in Georgia, and never move again. That sounded like a good deal to me, on whichever continent the house was located.

It sounded like a good deal to my husband too. In the 1980s the Army went from eighteen divisions down to ten. The battalion commands that were the career goal for most officers like Mike in the first fifteen years of their careers were disappearing before their very eyes. These days, if you couldn’t leap tall buildings in a single bound, you weren’t going to get one of the few commands that were left. There was a price to be paid for almost two decades of peace, and today’s field-grade officers were paying it.

To his credit, Mike proceeded to excel anyway by working hard for his soldiers and having commanders who were still soldiers enough themselves to be impressed. He got all the jobs he was supposed to get as an Infantry major because each commander he was assigned to ended up recommending him for the next job he needed. They all wondered how the hell this guy hadn't been picked up for command, forgetting that most of the battalions they’d had in their day didn’t exist anymore.

In years to come, whenever I attended the retirement ceremony of a general officer who commented on how lucky he was to have the opportunities he had enjoyed in the Army, I always thought, "You’re damned straight you were lucky because if anything had ever gone the slightest bit wrong in your career, you sure as hell never would have seen stars on your shoulders.” In all fairness, I must admit most of the generals I met made it that far by pure leadership skills. But the fact still remained that nobody made it that far without also being lucky.

As my pre-teen daughter would say, “Bitter – party of one.” But give me the benefit of the doubt. We're talking about the man I love, the father of my children, the person I've gone to the ends of the earth with, the other half of "us" when it was us against the world. Hurt him and it's not that I'm bitter. It is not that I don’t forgive. It is that I don’t forget. That’s being an Army wife.

So now the goal for us was making it to the twenty-year mark and retirement, and doing the best we could do for our family in the process. We were facing an unaccompanied tour. There was no way around it. But there was no reason to fall on our sword either. Command was not going to happen. Promotion to lieutenant colonel was the new goal. Mike accomplished everything he was supposed to on his career track that was within his control. We knew the rest of it was out of our hands.

Making the sacrifice as a family to take the Korea assignment would accomplish nothing. To our way of thinking, there were two reasons to take the Saudi assignment. Number one: it was peacetime. There was no reason to separate the family if we didn't have to. Number two: it offered a great opportunity to travel right when our kids were the perfect ages to do it. The assignment came with an allowance for a trip back to the States each of the two years of the tour. You could take that money and go anywhere. Mike already knew he wanted to go to Kenya and New Zealand. I didn’t know anything much about either county, but Kenya and New Zealand sounded fine by me.

So Saudi it was.

***

This is the first chapter of a non-fiction account of my experiences as an Army wife living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, in 1990-1991 during Desert Storm, which became the First Gulf War.