Neighborhood and Nation in Tokyo Review

A government has many levels and many areas of interaction with its people. In the United States, if one was asked about the "government", then the image that would probably pop to your mind is that of the national government - Congress debating in Washington, the President signing orders, various departments working for administration. Yet there is also the state government, and below that counties, cities, a wide variety of associations either public or private, and many more diverse arrangements. It is in examining government, policies, and associations at the local level in Japan, that Neighborhood and Nation in Tokyo: 1905-1937 by Sally Ann Hastings, enters the fray. Its claim is that the local level in Japanese pre-WW2 politics has been ignored in favor of emphasis on the military and the big political parties, and that the interactions between Japanese municipal bureaucrats and government officials and the general urban population was not one of inoculation of militarism and reactionary sentiment, but rather was strikingly similar to the political and social policies pursued by their counterparts in the United States. Social welfare, non-partisan politics, clean elections, and a pluralistic society willing to tolerant dissident voices in the goal of fixing social ills constituted their objectives according to her, and they were furthermore broadly successful, even if limitations and the course of history ultimately led nevertheless Japan to disaster and ruin.

Chapters

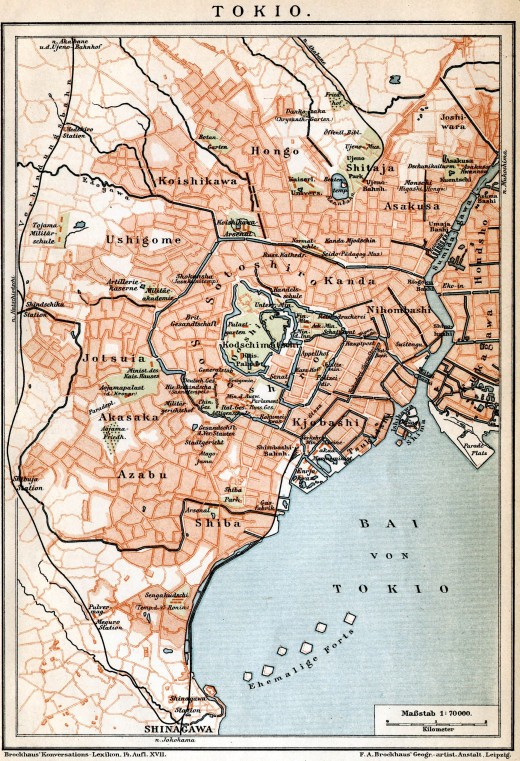

The introduction to the book lays out what is the objective of the book: in essence, the author is of the opinion that in studies of Japanese politics, too much focus has been placed upon actors from higher strata of society such as party leaders and the military, and not enough upon the interactions of average people in the state. This has led to the idea that Japanese popular participation in civil society was limited, and in particular urban areas have been ignored with only focus on small cities and the countryside. Conversely, the author claims that the Japanese context was an analogous one to developments elsewhere, and that while it had elements of state-direction from above, such as bureaucrats pursuing government-sponsored social policies, these were in essence the same with their focus as even the liberal democracies. It furthermore specifies the geographic focus of the book, the principally working class Tokyo ward of Honjo.

Chapter 1, "The Setting", explores Tokyo more in depth. Tokyo was radically different in its problem of poverty than in the countryside, and this highly visible poverty was a dangerous phenomenon for an important capital city, leading to various attempts to control it. Such efforts focused more on keeping the poor invisible, such as confining beggars to a city district when a Russian prince visited in 1870, than genuine efforts at social aid, which were limited. Poor relief was the responsibility of local governments, and philanthropy, according to an ideology which viewed poverty as a matter of individual and social, rather than national, responsibility, despite attempts to promote alternate views such as the German model of seeing poverty as an ill affecting the national organism and poverty relief as a cure. The state's involvement occurred mostly in regards to promoting private philanthropy, and it wasn't until the Great War when an acute social crisis developed that the first efforts at substantial government intervention began to appear.

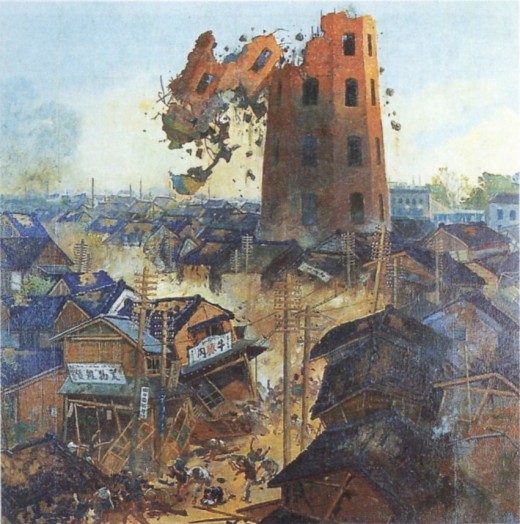

Chapter 2, "The Social Policy of Tokyo City, 1919-1937" deals with the actual policies of the new Social Bureau in Tokyo. The commercial elite was still uncertain about the idea of government social services, but nevertheless the new organization developed, aiming to help to correct a variety of social ills in Tokyo (usury by pawnshops, lack of housing, inadequate medical care, unemployment) and ease the life of the poor through programs such as reducing infant mortality. Its reach grew to a great extent after the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake, which killed a hundred thousand people and left 60% of the city destroyed, requiring additional aid afterwards. There was also private charity, which often did not conform to the state's objectives, such as socialist and Christian philanthropy which stirred up labor unrest. But the state proved willing to accept and tolerate a wide variety of these dissidents, even to encourage them, in the interests of achieving its social objectives. This went so far as even Korean social organizations in partnership with the state, as part of an effort to provide a role for Koreans willing to accept their place in the framework of the Japanese state.

Chapter 3, "Residents Leading Residents", talks more about organically grown developments created by the residents of Tokyo for their self aid, assistance, and government. Here, their center-stone were neighborhood associations, called "cho", that were voluntary and helped out for cultural activities, financial support in hard times, health, and community solidarity. While many claimed descent from Tokugawa-era self-government organizations (which had been very widespread), they changed constantly over time, had dramatically different organizations, and were effectively modern developments. The government welcomed them for both their assistance and their moral role, seeing them somewhat akin to communal village organizations. Their leadership tended to be petite bourgeoisie attached to their neighborhoods, instead of the big capitalists, bureaucrats, or new professional classes. Despite some conflict with neighborhood associations early on, bureaucrats as mentioned embraced and even expanded the role of local organizations, such as with welfare committees staffed by volunteer local responsables to carry out social work. These in practice became heavily politiical, functioning somewhat like American political machines, and of course reflected class divides in Japanese society.

Chapter 4, "National Networks in the Neighborhood", deals with national-level organizations and their interactions with local life.The Imperial Military Reserve Association was one, functioning as an organization for military reservists. In the countryside it essentially melded onto rural organization, but in the city it was much more fluid and diverse. It functioned both for patriotic and also civic activities, as well as things such as orienting rural military reservist migrants into urban life. The other major national network were young men association, formed for encouraging patriotic education. These reached a very large membership size, up to 3 million members, and were like their rural counterparts dramatically different in the urban environment due to lower membership rates and more heterogeneous participation. The two different organizations have been seen as a way to indoctrinate youth into militarism, but the author reverses this and claims that conversely they were tools which were utilized for expressing a groundswell of ultra-nationalism, and they were very much their own actors. Furthermore, not all were homogeneous, and some were pacifist or socialist, or allied with union or labor interests.

Chapter 5, "Factory, Union, and Neighborhood", concerns the relationship of Japanese factories and their unions to daily life in Japanese neighborhoods. There was a distinct difference between large factories which were removed from neighborhood life, and small factories that made up part of social fabric. Pre-WW1 the unions which were founded such as Yuaiki were very conciliatory, focusing on worker-self improvement and aid and placing little emphasis on strikes; and operating principally in a local context. During and after the First World War it became more radical and nationally oriented. Honjo was the site of a wide variety of strikes, at first in the large factories, but increasingly in small and medium factories after the 1923 earthquake. Although Japanese labor had never been aggressive in its demands, it nevertheless was a pluralistic force in society which sometimes achieved its independent objectives.

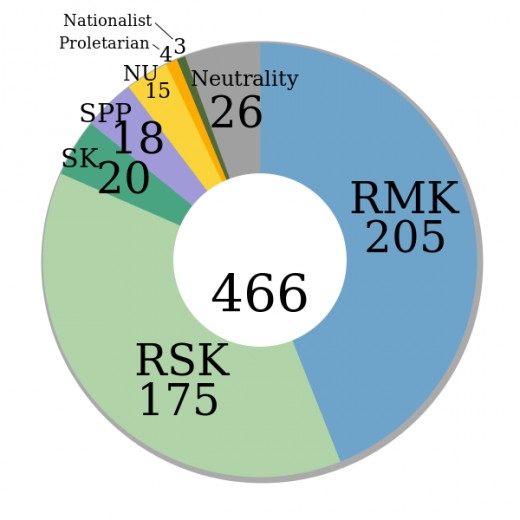

In Chapter 6, "Urban Voters" is principally concerned with the actions of Japanese mass voters after universal male suffrage was granted in 1925, painting a positive picture of their enthusiastic participation in Japanese elections. The introduction of universal male suffrage started to dramatically change around how elections were run and why people voted in them, as a much expanded voter base existed which placed greater emphasis on national, rather than local, politics. This undermined (alongside the introduction of new technology and campaigning methods) the traditional two big Japanese parties, although for the first two elections after 1925, when universal male suffrage was introduced, they were able to continue to keep their control in the face of their opposition's lack of experience and coordination. However, the "proletarian candidates", representing worker and mass public interests other than the two big parties, and other new parties, were able to increasingly challenge the large parties in 1936 and 1937. Rather than seeing this as a failure of the Japanese political system, it should be looked at in a more positive and accepting light, where there was more, not less, pluralism in the civic sphere.

Chapter 7 is the conclusion. It concludes by saying that Japanese political participation and complexity had expanded steadily from 1905-1937, producing a more pluralistic and politically diverse society. This had been encouraged and aided by the Japanese state, through its agency of the Home Ministry. Rather than effectively expanding state power, this had principally enriched the social fabric of the city. The bureaucrats had effectively acted much like their counterparts in the United States or other countries, in seeking to edify their city to answer social ills and counter the threat of revolution from below. If there were limits to their liberalism, they still should be understand in the context of the same ideals and the same concerns, and in many ways the same outcomes, as their counterparts elsewhere, and helped prepare Japan for democratic government post-war through local self-government.

Appendixes, bibliographies, notes, and an index constitute the end of the book.

Review

Principal among the problems which the book contains is in my opinion the relative lack of information about how average people reacted to, felt about, and were encouraged or discouraged from participating in many of these projects. For exaple, it is mentioned that there were a relatively vast number of men in the Young Mens Association, admittedly with major differences between the rural and urban areas, but the reason for why there seemed to have been such enthusiasm for the organization isn't mentioned. What did young men think about it and why did they join? The same can be said about a lack of dissenting narratives covering many of the organizations, particularily the neighborhood associations. Surely there were those who rejected or looked unfavorably on them? Even as minority view points, they would enable a better understanding of what the Japanese people thought about this. The book had declared that one of its objectives was to see how policies actually interacted with the Japanese population beyond just the declarations of government, and in my opinion the lack of how the Japanese people interpreted this is a grievous failing for carrying out this promise.

Furthermore, the book doesn't to me seem to really focus on the Honjo ward like it had specified. Honjo does pop up occasionally, but Honjo is not really the focus of the book, instead it is at most utilized as a stage for elsewhere. The amount of detail devoted to Honjo is in my opinion, rather superficial. The book is not about Honjo, Honjo is simply a prop for elsewhere. If one is looking for a microhistory of a Japanese ward and its neighborhood in Imperial Japan, this book would not be appropriate.

Finally, the author seems to be entirely too sanguine about bureaucrats, the state, and the people and their relationship to fascism. If the state helped liberate the social sphere, and yet it was this social sphere which autonomously acted in favor of militarism - as she claims concerning the Young Men's Association - then does this not speak of a deep and important connection which requires explanation concerning how popular energies lead to Japanese militarism? This is ignored and not mentioned, brushed over, and instead only a positive linkage to post-war democracy displayed. It leads into a general theme in that I think that Hastings overplays the democratic elements of the Japanese system, and this undermines her thesis.

However, despite these critiques the book is quite useful. As a description of the social welfare programs which the Japanese government adopted, it provides a comprehensive level of detail, moving beyond the generalities to look at how these programs interacted in local life, with plenty of information about their broader meaning and their role in political life, as well as the conflict which they occasioned between bureaucrats and the volunteers who ran them. While I am unconvinced by the fullness of her thesis, nevertheless vital elements of it, about a state (or more precisely, a section of a state with Japanese social bureaucrats) which encouraged a degree of pluralism and was defined by benevolence seem strong. It lends an appreciable depth to understanding the Taisho and early Showa periods in Japan, and complicates the image of a Japanese abolition of democracy through showing the ways in which it actually expanded even as Japan slipped towards the Second World War through showing the continuing plurality of Japanese society and the un-achieved state domination. While union activities are probably covered better in other books, they receive a useful mention, and the discussion of national networks in the cities is important in light of the great focus placed on them in the countryside. This book is not perfect, and I think that it would have benefited from greater length to add in greater complexity and depth itself, and conversely perhaps a narrowing or splitting of its political focus concerning the simultaneous objectives of political participation and social welfare, However, it is still a valuable one for those interested in learning about politics in late Imperial Japan, its social welfare, bureaucratic objectives, union modifications, Tokyo urban demographics, and the organization of Japanese urban neighborhoods in principle.

© 2018 Ryan Thomas