So-Much-Makes-Sense-Once-We-Get-the-Connections3

Leaving Perth and Swan River behind

Scattered Images in my mind 3

Five years ago,

I took my youngest son

to meet his Grandparents in Europe

for the first time.

Five years ago,

he opened 'his diary',

looked at our aeroplane

and scribbled in it: THAI.

I bought a new book

at Perth airport -

like always on long flights -

to kill time.

'MAO'S LAST DANCER'

was the title.

The true story of an Australian,

born in Communist China who

found freedom in America ...

"Mum, I'm bored. When do we fly?"

I stopped reading and looked at my son.

Saturday 4-9-2004.

I ate my breakfast

on the Thai aeroplane,

flying to Bangkok from Perth.

We stop in Phuket.

My son has written in his diary.

When I'm reading it now,

I imagine all the greenery

that we saw when we landed.

Phuket disappeared the

following Christmas Day

under a big tidal wave.

4.24 pm and back on the plane.

I watch Garfield and Harry Potter -

the Prisoner of Azbakan.

My Mum's looking for my passport.

She cries. She's lost it.

It's nowhere to be found.

My son has written in his diary.

When I'm reading it now,

I remember a long night

in the Bangkok airport,

listening to the foreign sound

of the suspicious transit officers

telling me that my son cannot fly.

I hugged my son tightly

as he started to cry. A young Chinese man

sat next to us and said simply:

"Just call me Mr Nine."

He took us to the Hotel Samui

at midnight, Bangkok time.

While unpacking our luggage,

my book, 'Mao's Last Dancer'

caught his eye.

While my son slept soundly,

he ordered a green curry

and a bottle of Singha beer and

finally calmed me down.

He was born in Communist China.

A son, number nine.

His parents left for Thailand

when he was only five.

We discussed creative freedom

and a quest for self-expression.

That was what 'Mao's Last Dancer'

was looking for, but he paid a painful price.

He managed to free himself

of communist ideology.

Mr Nine was an artist too.

He was not scared of China.

But he was Thai and with his minimal wage

of five dollars a day,

he knew, and I knew,

that it was taxi driving and other odd jobs

that would help him too survive, and not his fine painting.

Three whole days we stayed there,

while my son's new passport was arranged.

With our taxi driver Mr Nine, we crisscrossed Aka Krung Thep,

the City of Angels, Venice of the East.

Chaos everywhere.

The Phraya River which snakes through it, divides the historic old city

with it's temples and palaces.

The districts of Dusit, Banglamphu,

Ko Rattanokosin and Chinatown are full of Buddhist wats,

street markets and public parks.

On the other side is a futuristic new city with skycrapers,

elevated highways, karaoke banquet halls

and gigantic shopping malls.

Ancient tuk-tuks and urban trains

and sleek skytrains run through it all.

While my son wandered through the grand corridors

made of gold, touching the biggest golden Buddha on his toe,

Mr Nine looked sadly from the Royal palace window

at the city below us, where the old meets the new.

Where the Eastern slow contemplative tradition

is swallowed up by fast crazy western consumerism.

"We need a massage," Mr Nine winked at us.

We followed him, not having a clue.

In the park under a sweet smelling tree, a young

Thai girl gently spread Indian and Chinese oils on our bare arms and legs.

"Your energy will now flow around your body freely."

Mr Nine sighed with relief. "Your body and your mind will be one."

"And what about Thai pirates?" my son jumped up impatiently,

brushing his oily cheek: "You promised me some..."

Mr Nine sighed again: "Oh. I see.

You westerners and your speed. It is time for you to learn 'jai yen'."

"What does it mean?" my son squirmed in his seat,

as the taxi honked, stopping on the crowded street.

I watched passing tourists shouting at tuk-tuk drivers

while drying their sweaty foreheads in the sticky heat.

Mr Nine waved to a group of locals on the other side of the road,

who sat waiting on their motorcycles in the traffic jam.

They waved back at him with broad smiles.

"What is 'jai yen, Mr Nine? " my son asked again: "Are we there yet?

And can you please put on more air-condition? I'm hot now."

We stopped near the river, watching the thin boats sail.

Mr Nine told us a story from the old days

about pirates who ravaged the Thai coast.

They came from Europe, India and the Persian Gulf

at the start of the monsoon.

They returned home rich, with their boats full of gold

and stolen Asian beauties wrapped in shimmering silk.

With his last words, Mr Nine smiled.

With a twinkle in his eye, he gave my son

a black and white pirate flag.

He told him that to become a Thai pirate,

he needed 'jai yen' - a cool heart.

To me, he gave a gentle water colour picture

painted with thin Chinese strokes.

A line of empty dark brown rickshaws was painted on the side.

"It is called 'A journey from poverty'",

he said, with a frown.

On our last day, when we said goodbye at the airport,

I handed him 'Mao's Last Dancer',

with a thank you note inside.

"I can speak English, but I need to read more,"

he said with a sheepish smile.

"I plan to go to Beijing to study Chinese Art.

I will write to you."

We visited Europe.

My son got to see his grandparents

before they died.

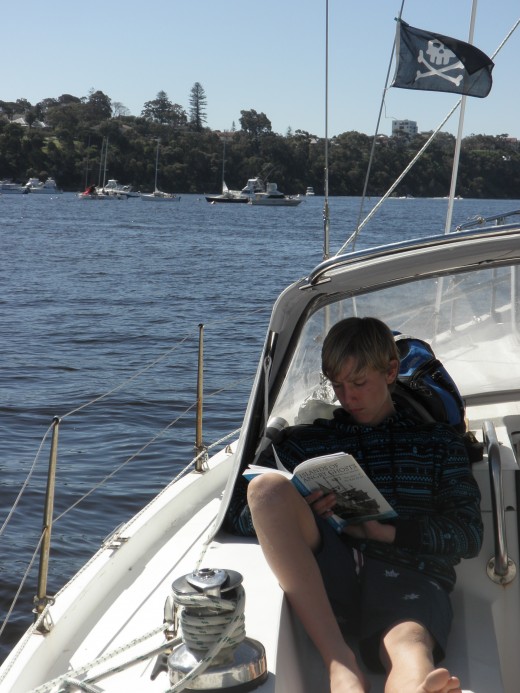

We returned to Western Australia

to sail on the Swan River.

To live, to remember, to laugh and cry.

Mr Nine sent only one letter.

After his Beijing studies,

he wanted to learn more about art

than communists.

He felt foreign and lost.

In the overcrowded city,

he met his Chinese family

living near the Yellow River.

On the vast plain around

the flat land, the city goes on forever.

New buildings appear overnight.

Roads are jammed with the latest cars.

Streets are full of fashionable people

with mobile phones clamped to their ears.

Business and money

are what everyone wheels and deals

in multimillions.

People live and die in vast shopping malls,

fighting for exclusive foreign brands,

while answering their mobile phones.

The ancient capital of Mongols,

the Ming and Qing Emperors is lost.

Communist ideology destroyed it's culture.

Western consumerism destroyed its identity.

Beijing is one gigantic shopping mall.

It's environment is dying, paying a living cost.

It's not a place for an ancient Chinese artist.

Mr Nine left.

I hope that Bangkok is still his home..

Five years have passed.

The Li Cunxin autobiography was made into a movie,

Mao's Last Dancer.

We watched it on a big screen, my son and I.

Licking our ice-creams,

we cried at his suffering in a gruelling

classical dancing class in communist Beijing.

We cheered on his fight

to dance free and be famous in America.

Then to fall in love

with an Australian

and to retire happy here.

Finally, he knows what it means to be free.

We went to sail on the Swan River,

my son and I.

His black and white pirate flag flying high,

from Mr Nine.