The Anaphora: the Poetry of Litany

The anaphora is one of the best overlooked styles of poems. It seems like almost all poems I write are influenced by this rhythm of litany in some way. The anaphora is of foundational importance to the essence of poetry itself, as it has long been employed in religious and meditative poems, which were some of the first recorded poetry in the world. Repetitious sounds, including the playful alliteration and the subtle assonance, are at once soothing and enlivening to us from a young age. It feels inexplicably natural. Sound has the power to recall physical sensation: it may remind us of being rocked to sleep in loving arms. The use of repetition is an incantation, of centering and grounding, and somehow of rousing to a deeper awareness through verse.

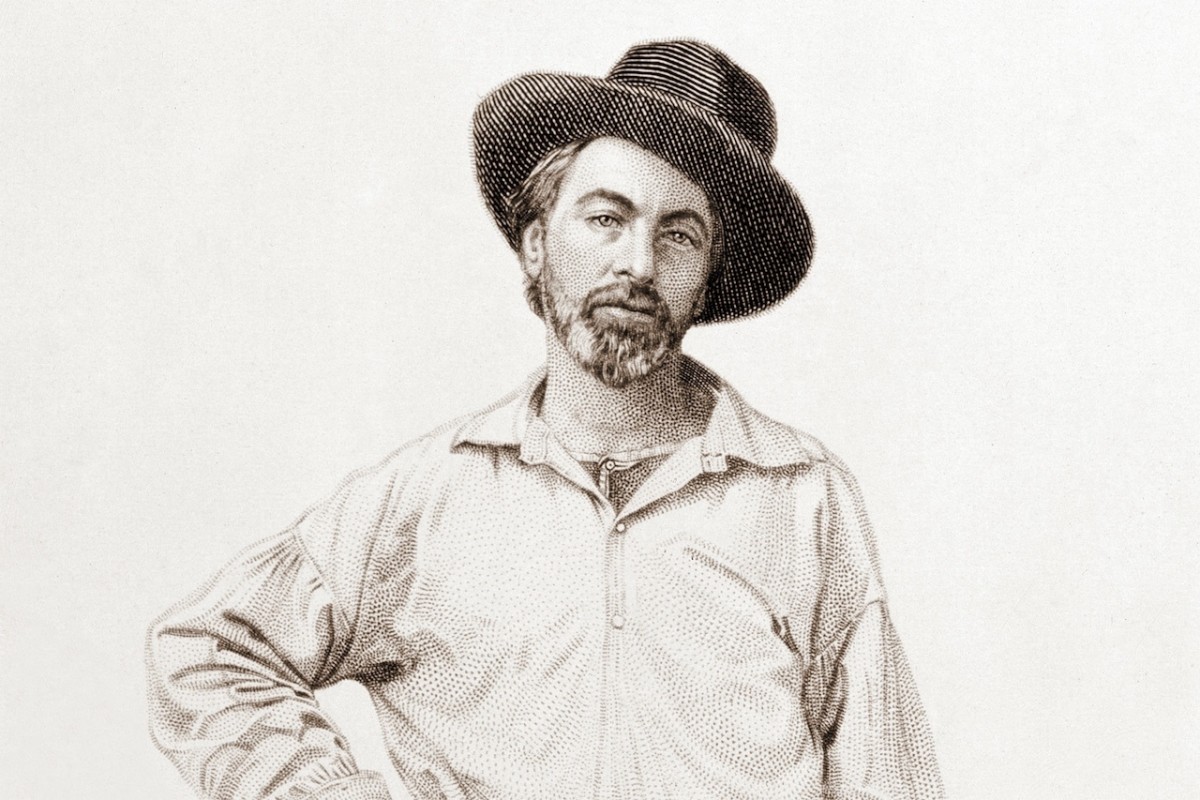

Walt Whitman: The Bard of Anaphora in America

Walt Whitman’s grand and soulful Leaves of Grass, and its famous segment, Song of Myself, is rich in these repetitions. Whitman, however, gives us the literary device of the epistrophe, the opposite of the anaphora, where the anaphora is the repetition of a line’s opening words and the epistrophe is the repetition of a line’s closing words. He writes,

I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the

beginning and the end

But I do not talk of the beginning or the end.

There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now,

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now. (“Song of Myself III” 1-6)

Whitman’s words are here overtly prophetic, a spiritual witness to experiential truth. His rhythmic epistrophe is characteristically insistent – the quality of insistence being a chief feature of anaphora and epistrophe– to the sacred point which he strives to communicate: that there is no time more alive, more riven with joy and torment than the eternal now which we bodily inhabit. The present is where all of the past and the future pregnantly resides. In his poetic genius he makes his poetry do that most astronomically difficult work of metamorphosing abstract words into immanent feelings. His words are true because they are spoken in honor and reference to primordial feeling, which is good and true and existed in the days before our species had words of vocal speech.

T.S. Eliot and Lyrical Time

T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock is similar to Whitman’s work in its visionary tone. Time is also a theme for Eliot, who stares into the eternity-of-the-now in the spirit of the old Irish saying, “When God made time, he made enough of it”. He writes,

And indeed there will be time

For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,

Rubbing its back upon the window-panes;

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create,

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea. (“Prufrock” 23-34)

In Eliot’s world there is time to be and not to worry, to break down and build up “a hundred visions and revisions,”. Perhaps this view of generous time, so unlike the monster of time in the modern world, makes us uncomfortable with its almost-sad tranquility of sameness, of sitting still with the grief and the raw beauty of time and mortality in the face of our everyday lives.

Anaphoric poetry brings a reminder of meaning to these otherwise nonsensical beats and pulses of life, offering moments of solace through doubt and change. It calls us back to Eliot’s slow sit and Whitman’s large sight.

Works Cited

Eliot, T.S. “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Literature: Reading Fiction, Poetry, and Drama. Ed. Robert DiYanni. 6th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2007. 1102-1105. Print.

Whitman, Walt. “Song of Myself (1892 Version).” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, n.d. Web. 17 Aug. 2015.

© 2016 Amber MV