The Brothers Karamazov's Portraits in Time: A Modernistic Review

How The Brothers Karamazov Qualifies As a Timeless Great Character Novel

The Brothers Karamazov's Portraits in Time

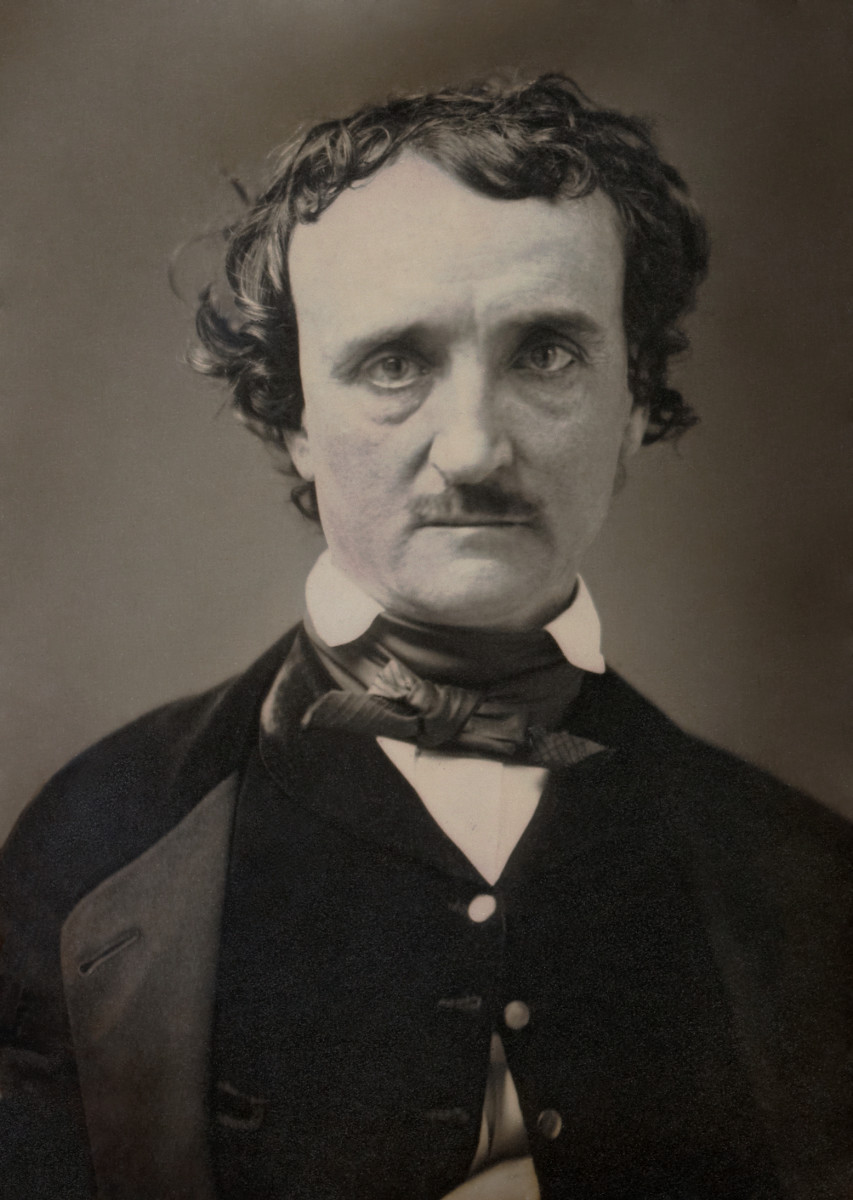

From tame and visionary Alyosha to the dashing and spontaneous Dmitri, the leering atheist Smerdyakov to the morosely philosophical Ivan Karamazov, there is a perfect snapshot of 19th century Russia in one family. To expand this string of thought, every modern reader can meet a character in the book either to sympathize with, vilely hate, or remember to have seen a real-life replica of, somewhere or other. Details froth and ferment as they run their course in this epic journey at the center of which is a land-owning family. These are two basic elements that make the Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky, possibly the greatest novel of all time. This is with the exception of perhaps Don Quixote, which appeared beyond two centuries earlier.

The Characters on the Modern Tableau

Whenever one revisits the novel, it is not merely because of the great chapters like the Grand Inquisitor or the fervor of the red-hot chapters on spirituality, atheism, love and nihilism. It is because of the linear remembrance of otherwise complex, and sometimes double characters, like Ivan. Ivan is the understanding student of theology in one’s class, a charming fellow to talk with, but one who can turn into a shadow at night. He appears very commonplace but is a deep thinker, and sometimes a planner of evil through the kaleidoscope of doing good acts. What else would motivate him to lead the devil, in the famous chapter, into a conversation in the first place, if the very act of personal interaction with evil incarnate, even while solving the problem of good and evil for the world, is not, in itself, blasphemy?

The character of Smerdyakov is also commonplace. He is the outcast of a village in any part of the world, whose luck lies in having a disease to call ‘my disease’ as modern people like to call their chronic tuberculoses, cancers or whooping coughs. His consumption makes him seem like a character one can forgive easily. Opposite of sympathy, however, like in all Dostoevsky’s characters, lurks a deep hatred for this greenish figure (as a paperback cover portrays him), an evil creature. He is one of the best creations of a character born for hate alone. No wonder the finger of blame after the senior Karamazov falls points to him exclusively before the lameness of an excuse catches up with Dmitri.

Dmitri is a character easy to delineate from society. The dashing firstborn of the family next door, who has every right to have a girl he loves, follow him anywhere at the expense of both the family coffer and the sulkiness of his juniors. He is bold and mad as a hatter if the chase that he carries out at odd hours to get Grushenka is anything to go by. Who wouldn’t do the same if having the same privilege of being the family head after the demise of an overbearing father? This completes his partial resemblance to a character one has ever met at the local level.

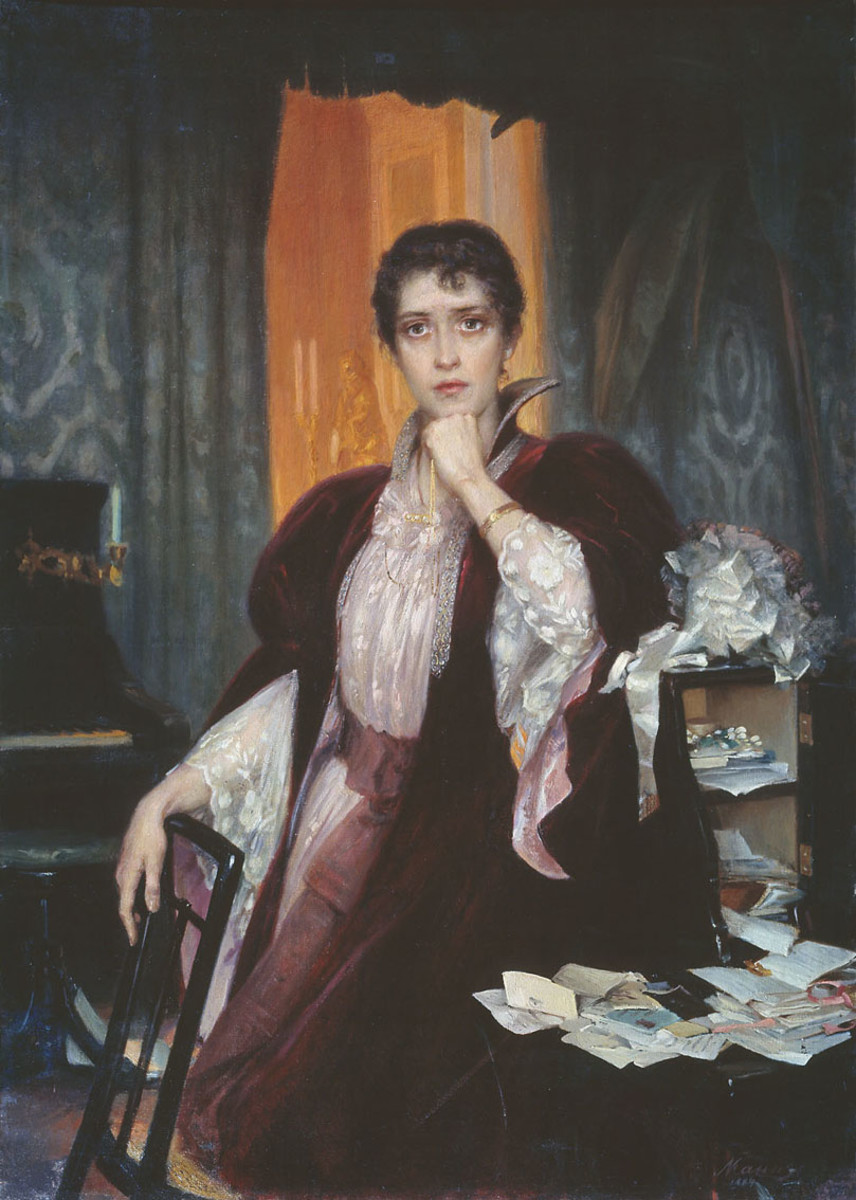

Grushenka is one of the heroines that command a following both by the reader and the fictional society. She attracts gossip, creates intrigue and possibly leads to murder. ‘What can’t love do?’ would be the rhetoric that embeds to her character best. Though overdrawn to a level of sacrilege by the author, she still, however, retains the flesh and gore that make her a real character that one is likely to meet in the high street at a hometown.

Alyosha needs no enunciation. He is both the symbolism and submissiveness of a last born who alone stands fast to rescue the family from the disgrace of seniors. With the exception of the misty chapters with Father Zosima that remove him from the world of men to that of angels, he is very likely the son of the local parish pastor in one’s neighborhood. He does what he does with a conscience, dreamy as it may appear, of whether it is purely wrong or religiously wrong. No wonder his chapters are especially technical weapons against those of Ivan, which one must admit are the greater of the two.

Here is an assessment of the above fact in the following section.

The Spiritual Themes of the 19th Century

The chapter of the Great Inquisitor and that of the devil are Ivan’s answer to the spiritual apathy of the century in question. They display, via direct symbolism, the self-questioning attitude of ‘why am I here?’ of the era. They still reverberate today, though to a devil-may-care proportion in the 21st century, perhaps because people are no more as idle as they used to be and have to attend to more practical things rather than questioning existence. However, the great thing about these chapters is that they anticipated similar themes of the 20th century that went into absurdity. From Samuel Beckett’s farce, Waiting for Godot in the Theater of the Absurd tradition, Franz Kafka’s surrealism and Jean-Paul Sartre’s existential works, there is something owing to Brothers Karamazov in all these styles. Many may cite the age of Freud where spirituality, secularism and sexism found crossroads but the fact of the matter is that Dostoevsky first evaluated the question in a long fiction format, beyond the long essays of Voltaire and other prior philosophers.

Alyosha’s version of the 19th century was the ideal of Fyodor Dostoevsky on how peace and harmony should bless the world. Though his contact with Father Zosima has an aura of visiting a medieval monastery, it still reflects the commonplace religious sects, which are more than ever before, in the current times. The link between religion and the purity of the world that Alyosha symbolizes is apparent in all these chapters.

Conclusion

The latter assessment of two chapters makes it possible to read Brothers Karamazov in two stages. Firstly, as the Life of a Great Sinner, apparently the title Dostoevsky died working on, for Ivan’s chapters and then the life of a Saint, so to say, with regard to Alyosha’s chapters. The rest of the descriptive details can fall in wherever they are necessary. However, this is not just what makes the novel great: in fact, critics attribute the failure of Dostoevsky’s works in the lack of a consistent plot which is why the above two-part reading may fail. The other way is to remember which part of the book where one first met a character who closely resembles a friend or foe, currently living. Removing the six main characters of the five-member principal family and Grushenka, one comes across a myriad of characters that even leave sharper pinpoint portraits than these. They are what makes deep readers feel grand to be a part and parcel of the scum of the earth in the novel. This is because their development is partial and thus sufficiently reveals without the need of apologias that one would have handy to justify a complex living fellow like Ivan Karamazov. No other great book nears the above memorable attributes.