The French in Central America Review

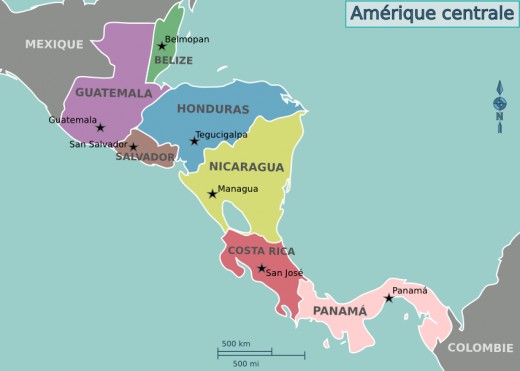

France was (and continues to be in many ways), one of the great imperial-colonialist powers of the 19th and 20th century, and in addition to its formal colonies, widespread and around the world, it also had an extensive network of countries where it had a great degree of informal influence. There, French commercial, economic, cultural, and political interests were present, as the French sought to advantageously improve their own position for the benefit of their country. The story of this relationship in Central America, where French influence played an important role alongside other powers such as the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, as well as others, is one which is analyzed by Thomas D. Schoonover in his book "The French in Central America: Culture and Commerce, 1820-1930".

In the introduction, the author stresses the importance of what he terms "social imperialism", as European states attempted to expand their influence and economic control, often outside of the formal boundaries of their empire, to cope with domestic economic and political problems and attempt to gain increased power and prestige. However, the various metropoles (the centers of power, finance, industry), in Europe and North America competed with each other to control the periphery regions, which were themselves exploited and modified by the metropole states - Central America being a principal example. The rest of the book follows into the line of defending this point.

This continues with laying out the initial French position in the region, where the French had had a degree of influence and connection to Central America since before even the states had become independent, and lays out how the French military sent ships into the region to assert its role. The French had an important economic role, but their biggest hope seemed to be, even from the beginning, to control the transit rights across the isthmus as part of the increasing globalization of world trade. Under Napoleon III their policy became more assertive, claiming a common Latin Catholic civilization which had to stand together against the Anglo-Saxon and Protestant Americans, although this was complicated by distaste for the French invasion of Mexico and the desire to work alongside the also Anglo-Saxon and Protestant British. After a temporary fall of French interest with the defeat of the French Second Empire, the French returned to attempt to build a canal in Panama, which ultimately failed and had to be sold to the Americans, who had not been particularly overjoyed about the French involvement in such a significant project in the region.

Later French policy proved much more conciliatory to the Americans, viewing the increasing American influence and what essentially amounted to the transformation of the region into an American protectorate, as being a positive aspect that would benefit Europeans by enabling their own trade and commerce with a now stabilized and secure region to expand. This was not really the case, as the American's strengthening position principally accrued benefits, above all else, to the Americans. However, if French trade declined, French financial interests grew dramatically, and the French also expanded their cultural influence in the region. During the First World War, the French position deteriorated even further, evaporating even more quickly than the Germans, and losing ground to the United States. However, the moral position of France and its cultural prestige seemed to come out very well from the war. After the war, the French were able to modestly win back some of their previous position with additional investment, cultural politics, aviation development, and the return of French trade to some extent. Ultimately, the French role would be utterly expunged by the collapse of France in the Second World War. A conclusion sums up the general trends and ties them back to the introduction

Many histories are simply bilateral ones, but The French in Central America does an excellent job in relating the relationship between the French, the other powers present in the region, and the various countries which they were actually interacting with. The French worried about rapprochements between the British and the Americans that threatened to squeeze them out, about growing American power, had to juggle relationships between different states, and about the growing role of the Germans in the late 19th and early 20th century. All of these heavily influenced French decision makings, as the French sought to expand their trade, commerce, and influence, in a region where competition was fierce and strong.

At the same time, the very statistics and tables which the author provides show that the French, despite their objectives, only had as a percentage of their total trade a tiny part of the region's commerce. In this regards, it could raise doubts about whether it actually was quite as important as the author tried to argue, in regards to its role in providing for an economic safety valve for metropolitan Europe and its problems, since it was simply so small.

Is that to say that the author is wrong? By contrast, despite the limited French role, the French had a wide variety of plans that they proposed to attempt to ameliorate it. Despite none of these truly working, as French economic influence, although perhaps significant to the regional economies, was never a very significant part of the homeland's economic prosperity (as can be attested at the end by the economic tables which show that the total Central American percentage of French trade never managed to eclipse a fifth of a percent, and French investment, while larger, was still dwarfed compared to the total French involvement in other regions), the intent of the French to attempt to use the region as a zone of their informal economic influence shows the author was broadly correct in his views, at least to my opinion. It does represent a view which seems rather pronounced among the experts on Latin America, as a previous book upon colonialism I had read, which while unlike this one not purely devoted to Latin America but with a heavy influence upon it, Expansion mondiale et dépendence occidentale, largely shared the same view. These authors seem broadly correct - but at the same time it seems to me that quite different conclusions are drawn about the general objective of colonialism depending upon the region studied.

While the book certainly does focus on the cultural role which the French played, to me it seems like there could have been plentiful room to further expand this. Mention and discussion is made of the network of French schools, some of the cultural policies promoted by the French government, the belief that the French certainly held that the Central Americans were predisposed towards French culture, French awards and honors, etc. But at the same time there could have been more discussion about the way in which this actually impacted and changed, or did not do so, Central American attitudes towards France in real terms. The detail is very skimpy compared to the amount that concerns the economic affairs, and generally ignores the broader reception of French culture among the inhabitants of the region - how much in the way of French luxury products, architecture, philosophy, literature, French education and governmental concepts, and the other panoply of traditional elements of imitation of the French model and liking for France, did they consume? This book is very heavily titled towards the "commerce" side of affairs, and culture is conceived only in limited terms, mostly in the regards of the hopes displayed by the French political and diplomatic leadership, and much less in the way of its actual existence and relationships. Indeed, the French most vigorously mobilized this cultural effort precisely when it appeared that their economic or political role was most challenged - be it under Napoleon III in response to the increase of American influence, or during the First World War when the economic disruption of the conflict prevented the French from playing a significant role.

For an exhaustive recounting of the nature of French economic influence and economic objectives in Central America, married to a broader critique of the structural imbalances between the Central American and Metropole economies, this book is an excellent resource. For anybody who likes economic charts and analysis, the formidable listing of documents at the end is extremely useful. Along the way if illustrates broader principles in the international economy and provides a very sophisticated and impressive recounting of the French role in the region. For all of these reasons, it makes The French in Central America: Culture and Commerce, 1820-1930, an excellent and irreplaceable book for understanding the French role in the region, the broader principles of foreign involvement in Latin America, Latin America's structural transformations in response to foreign powers, and the diplomatic relationships between these predatory foreign nations that sought to reshape the region to their own advantage.

© 2019 Ryan Thomas