The Use of Maps and Outlines in Works of Fiction

Outlining Works of Fiction

For a professional fiction writer, outlining over time may become a mental exercise, something he does in his head as he moves his story along. Chances are, he didn't start out that way. His first works were probably outlined on paper in some way, briefly perhaps, with paragraphs of chapter divisions; or with intricate sidebars; or, possibly, by use of the traditional, as below:

A. Chapter One

....1. Tommy awakes suddenly

........a. moon is bright through curtains

........b. night breeze is sweet

....... c. Tommy thinks of Karen

Outlining fiction is more difficult by sheer content than is a work of non-fiction. A non-fiction presentation has several points to make, which easily can be whipped into a first-to-last, or last-to-first alignment of importance.

Fiction is far different, for many times the writer doesn't know exactly where the story is going, or one character takes on more importance than planned, which may change the story and its direction. Fiction is cantankerous with curves, highs and lows, blanks, and pitfalls, unanticipated roadways that develop on their own, so to speak.

Outlining can also change with the story flow, however, keeping the writer on the general track of the ideas he wanted his characters to convey. Using a separate, small spiral notebook for the traditional outline will ensure better organization, as well as allow for expansion and changes in the outlining process.

Guides for Outlining

Outlining a work of fiction is a personal matter; that is, it should take on the persona of the writer. A writer who chooses a method of outlining that doesn't suit him, or his particular way of thinking about his writing will struggle with the outline. Outlining should be a writer's best friend, a tool he chooses, to help him organize and maintain his course.

The traditional outline, as seen above, may seem a tedious and overly long task even to the extremely organized writer. But nine times out of ten, the extremely organized wordsmith will choose to use it because it suits his thinking processes.

The Sentence Method...

A good choice for the writer who sees his work in the "big picture" may be the sentence method. The sentence summary works as follows:

A = A general sentence describing the story's main idea

......1. Describe the story's conflict

B = Name the story's protagonist (main character/narrator)

......1. What is his conflict?

......2. Name the antagonist (protagonist's chief opponent/conflicting character)

......3. Who is a supporting character? How does he fit into the conflict?

......4. Next character/conflict

......5, 6, 7, etc. characters and how they relate to the conflict

C = Describe the story's developmental steps

......1, 2, 3, etc. (descriptions of each step, each of which will become scenes, or the core of single chapters

D = Write one sentence about the story's climax

E = Describe in a single sentence the story's resolution (ending)

Using the above breakdown, the writer can extend his outline by writing a brief summary of the entire story. Six to eight sentences may be used to achieve this in a "flash fiction-like" approach, which will put characters, complications (developments), climax, and resolution right in front of the writer at all times and guide him from beginning to end.

Introduction, body, and conclusion are the simple developmental building blocks of any story. The sentence outline keeps them organized and flowing.

The Notebook and Note Cards Methods...

Many writers use a notebook, or note cards to record their daily observations, or incidents that strike them as "book worthy". A notebook itself can become a tool for a project outline, as the writer thinks out his ideas and records them in organized, divided sections of the notebook -- characters, continuing conflicts and developments, and the like -- before he actually begins writing his story.

Note cards are another animal. The principal reason for using them as writing tools is that they are easy to sort and organize into categories and they handily are stored in a note card box, if preferred.

They may be the method a writer uses for research notes at the library, or in his general daily routine. He can divide his cards into notes on characters, the story's plot, its setting, conflict, climax, and resolution, thereby creating an organized outline resource.

Outlining is really a matter of choice for each writer, depending on his comfort zone.

Creating A Story Map...

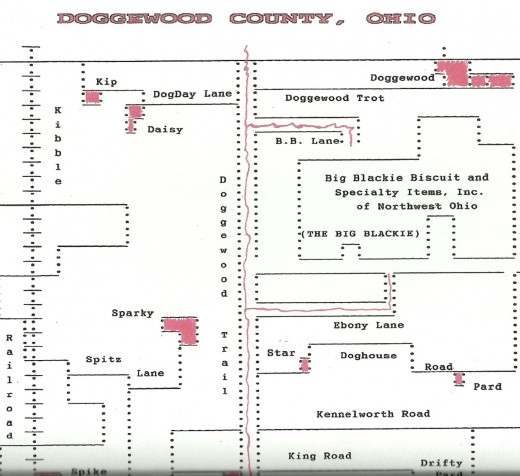

Some writers can visualize their story more clearly by using a story map which they create. Formulating an imaginary town, county, or city in which his story takes place can bring the writer's story into greater focus.

Where is Kibble Railroad in relation to Spitz Lane and the Big Blackie Biscuit and Specialty Items, Inc. of Northwest, Ohio, plant? If the writer can see it mapped out himself, he will be better at describing his settings to his readers.

Maps can be good writing tools, just as well as outlines. Maps give a sense of substance and place. They are a snapshot of where a story is born and grows. Working on a story map can also enhance the writer's creativity, give him a picture of time and setting and movement of his characters, and even clear those days of cloudy indecision about what comes next.

As with outlines, there are no definite rules that govern story mapping. A map can be precise, a project of itself beyond the writer's story that helps him relax and absorb his tale and its characters. It can be a separate, organized place to which the writer goes for inspiration.

Scribbles of streets and stores and houses work just as well for writers who want to have a visual aid but need to get on with the story writing while the keyboard (or pen and paper under a tree) is hot.

Rules Don't Apply

Plan the work, then work the plan is a common adage. It applies to writing as well as any project. Almost every writer plans his work with some form of outlining, mentally, on paper, with note cards, or in some inventive way that suits his purpose. Literally mapping out his settings may be part of his plan.

What is important to remember is that every writer may choose his own method of planning his work and working his plan. In the end, there are no rules for the use of outlining and mapping in story creation. It's a to-each-his-own field.

- The Bliss of Correct Punctuation

How to correctly produce a very long sentence. View a precedent for and the joy of the long-long sentence and its meaning, by James Fenimore Cooper.