- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Commercial & Creative Writing»

- Creative Writing

Thirteen Thousand Rats: Or, the State of Literature Today

I subscribe to The New Yorker. Here in the Ozarks this is unusual. A local educator who had volunteered to work with Bow on his English once remarked: "You always have such strange magazines lying around."

The New Yorker has great cartoons, interesting articles, and it opens a window on a world that is not available to me out here in the country. But the real reason I subscribe to the New Yorker is the fiction. And it's not exactly because I like the fiction. It's because I'm curious about what passes for good literature these days.

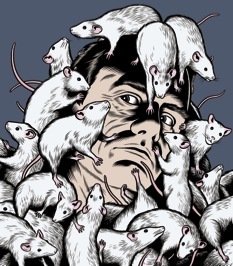

One day, I was leafing through the New Yorker when this illustration jumped out at me. It was of a man covered by white rats, and it went with a story entitled "Thirteen Hundred Rats". I said to my daughter: "Look at what they publish, instead of my stories!" My daughter turned to me and said: "Well, maybe you should try to make it more clear what your stories are about. For instance, this one is very clearly labeled. It's about thirteen hundred rats, so anyone who wants to read it knows right away what it's about. And secondly, there's a picture that shows very clearly what it's about. When you send in your stories, you should attach a picture that shows what the story is about."

I had to laugh. Yes, that would solve the whole problem!

My daughter's take on the issue was refreshingly simple. While she was mistaken about the mechanics of story illustration -- an accepted story gets an illustration; it doesn't get accepted because of an accompanying illustration -- she did have a point.

The New Yorker stories, no matter how well polished the prose is, are primarily concrete-bound. That is, the events of the plot don't seem to have an abstract theme that they are illustrating. So, in a way, what you see is what you get.

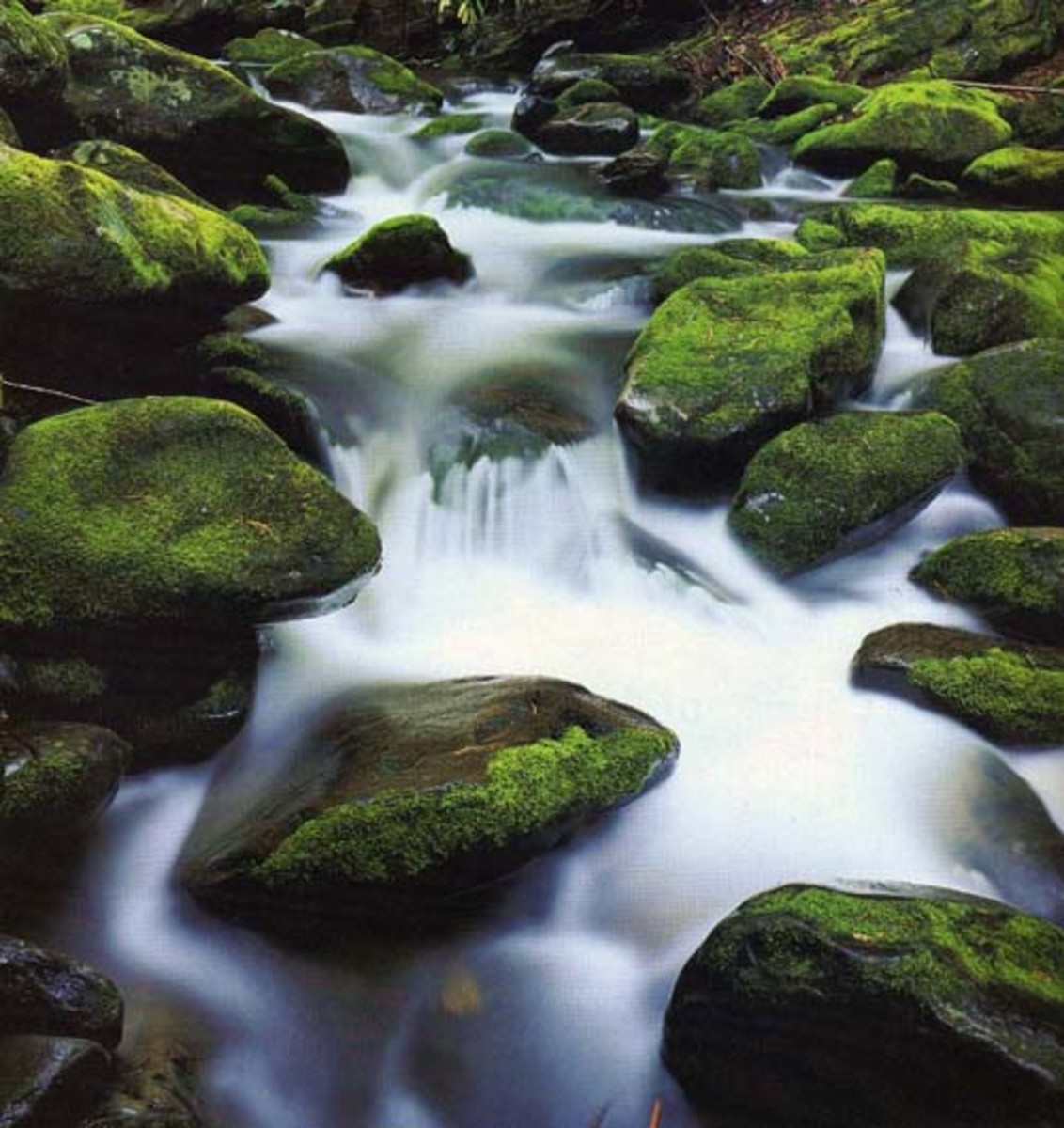

My own writing uses concrete events to explore abstract themes. It harks back to the prose of the 19th century, when plot and theme were closely integrated, and when a story wasn't really a story unless it had a beginning, a middle and end. The climax of the story would resolve both plot and theme, leaving one with a strong emotional and intellectual pay-off.

In contrast, the writing featured in The New Yorker tends to have straight-line plots that feature downward tajectories, little complication, and predictable endings.

For instance:

1. Bereaved husband buys a pet snake to relieve loneliness.

2. In order to feed the snake, he gets a rat.

3. Feeling sorry for the rat, he lets the snake die.

4. When he returns to the pet shop, he does not admit that the snake has died, so the owner sells him more rats, to feed to the snake.

5. The man is found dead several months later in a house swarming with rats.

If you think I'm kidding, follow the link to The New Yorker. You can read the story yourself. The question is: what is the reader supposed to make of this?

While "Thirteen Hundred Rats" is perhaps an extreme example of this, all of the stories in The New Yorker follow this pattern, to some extent. Annie Proulx is a great writer, in the sense that she is able to write page-turning prose with great descriptive power. But what does a typical plot look like?

- Two uneducated teenagers hook up, marry, and start a homestead.

- They are able to subsist on the land, but they get tired of it, and so the boy goes to work on a ranch as a hired hand.

- Meanwhile, the girl stays on the homestead alone in an advancing state of pregnancy.

- The baby is still-born during the winter, and when the girl goes to bury it, she attracts the attention of coyotes (or wolves) outside.

- The young man gets sick, and en route to a doctor freezes to death in a snowstorm.

- In the spring, neighbors discover that the girl was eaten by wild animals.

Most of the stories in The New Yorker have an unhappy ending, but that isn't the real problem. It's not tragedy that I object to. After all, one could write a story about Joan of Arc in which she gets burned at the stake in the end, and yet it wouldn't be a pointless story. It would be a story about heroism and the struggle of an individual for what she believes in.

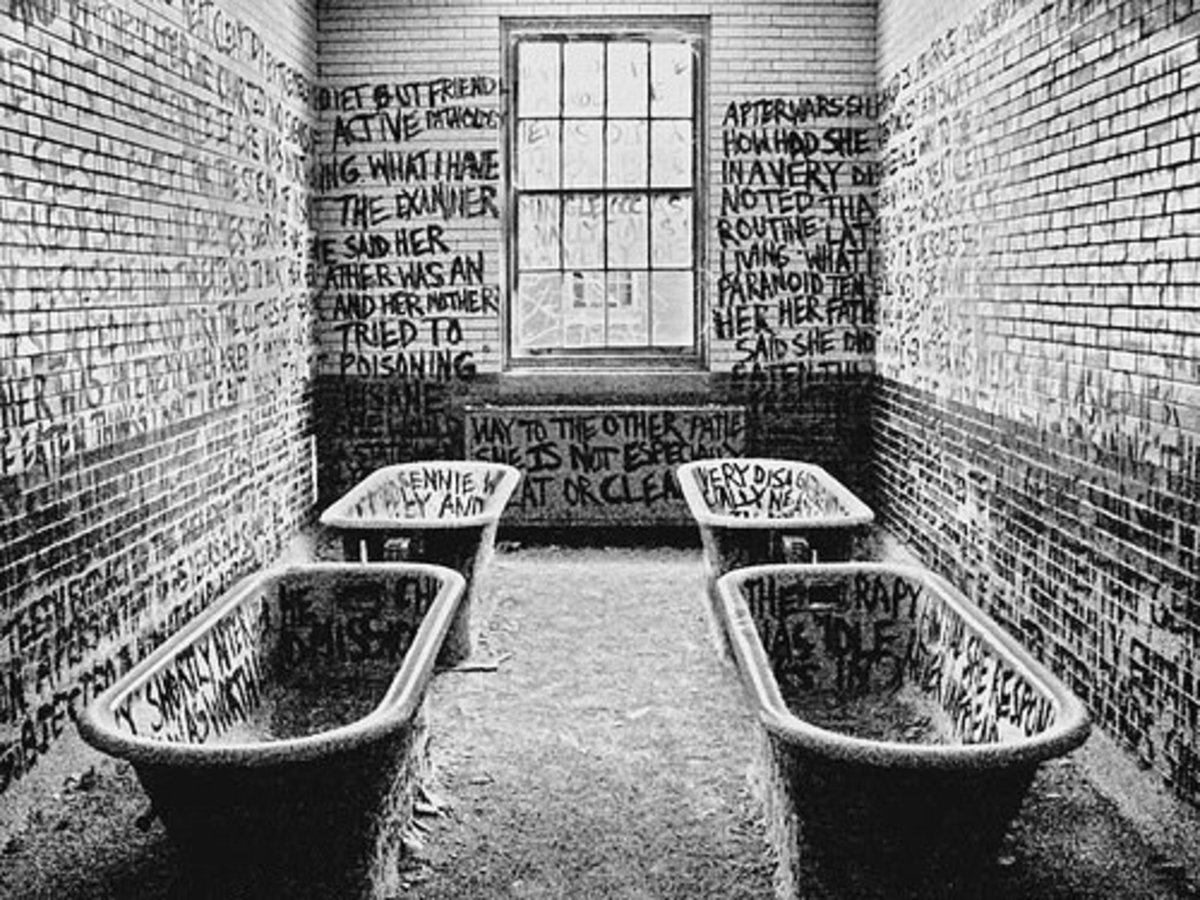

We can sympathize with Joan of Arc, even though she does die in the end, defeated. But the peculiar effect of the The New Yorker stories is that we don't sympathize with the characters. We are almost being asked to jeer at them as they die alone in tragi-comic circumstances.

Perhaps the straight-line descending plot that The New Yorker favors does have hidden thematic underpinnings. One comes away from these stories disheartened, feeling that not only the characters in the story have been belittled and dismissed, but that maybe all of us can expect the same treatment.

I will continue to subscribe to the New Yorker, because it represents the state of our culture today. The writers they publish have great skill, and I look forward to the day when they are allowed to direct their energy to saying something worthwhile.

(c) 2008 Aya Katz