Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Renascence"

Introduction and Text of "Renascence"

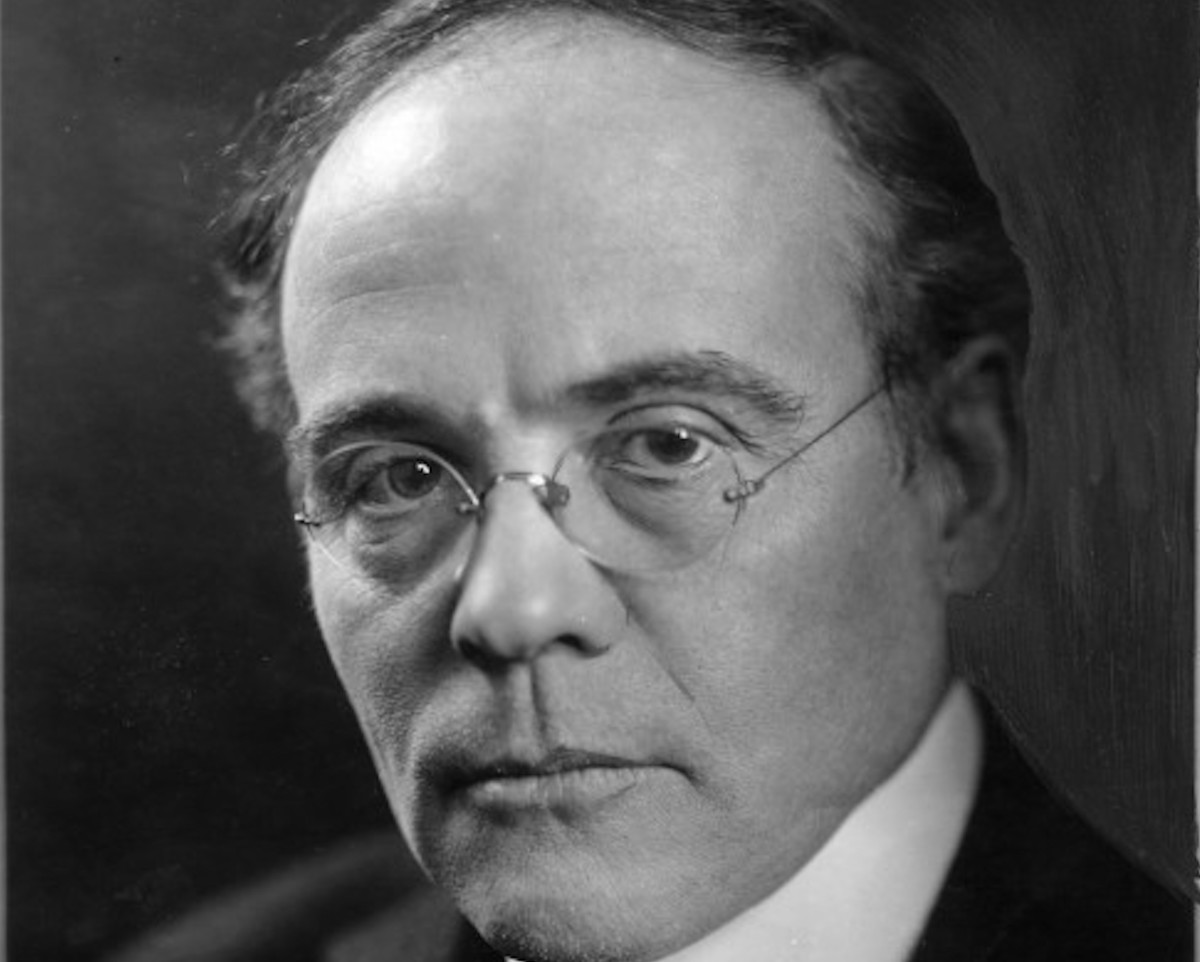

Edna St. Vincent Millay's poem, "Renascence," consists of 214 lines of rimed couplets. The poem dramatizes a unique mystical experience, made even more singular having been undergone by one so young. Millay composed this masterpiece when she was only twenty years old.

"Renascence" is pronounced [ri-nas-uhns], not [ren-uh-sahns], the label of that great period of the revival of art and literature called the Renaissance. Interestingly, the poet originally had title this poem, "Renaissance."

To hear the distinction in pronunciation of these terms, please visit, Renaissance on youtube and renascence at Dictionary, click on the speaker icon.

(Please note: Dr. Samuel Johnson introduced the form "rhyme" into English in the 18th century, mistakenly thinking that the term was a Greek derivative of "rythmos." Thus "rhyme" is an etymological error. For my explanation for using only the original form "rime," please see "Rime vs Rhyme: Dr. Samuel Johnson’s Error.")

Renascence

All I could see from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood;

I turned and looked another way,

And saw three islands in a bay.

So with my eyes I traced the line

Of the horizon, thin and fine,

Straight around till I was come

Back to where I'd started from;

And all I saw from where I stood

Was three long mountains and a wood.

Over these things I could not see:

These were the things that bounded me.

And I could touch them with my hand,

Almost, I thought, from where I stand!

And all at once things seemed so small

My breath came short, and scarce at all.

But, sure, the sky is big, I said;

Miles and miles above my head.

So here upon my back I'll lie

And look my fill into the sky.

And so I looked, and after all,

The sky was not so very tall.

The sky, I said, must somewhere stop…

And—sure enough!—I see the top!

The sky, I thought, is not so grand;

I ’most could touch it with my hand!

And reaching up my hand to try,

I screamed, to feel it touch the sky.

I screamed, and—lo!—Infinity

Came down and settled over me;

Forced back my scream into my chest;

Bent back my arm upon my breast;

And, pressing of the Undefined

The definition on my mind,

Held up before my eyes a glass

Through which my shrinking sight did pass

Until it seemed I must behold

Immensity made manifold;

Whispered to me a word whose sound

Deafened the air for worlds around,

And brought unmuffled to my ears

The gossiping of friendly spheres,

The creaking of the tented sky,

The ticking of Eternity.

I saw and heard, and knew at last

The How and Why of all things, past,

And present, and forevermore.

The Universe, cleft to the core,

Lay open to my probing sense,

That, sickening, I would fain pluck thence

But could not,—nay! but needs must suck

At the great wound, and could not pluck

My lips away till I had drawn

All venom out.—Ah, fearful pawn:

For my omniscience paid I toll

In infinite remorse of soul.

All sin was of my sinning, all

Atoning mine, and mine the gall

Of all regret. Mine was the weight

Of every brooded wrong, the hate

That stood behind each envious thrust,

Mine every greed, mine every lust.

And all the while, for every grief,

Each suffering, I craved relief

With individual desire;

Craved all in vain! And felt fierce fire

About a thousand people crawl;

Perished with each,—then mourned for all!

A man was starving in Capri;

He moved his eyes and looked at me;

I felt his gaze, I heard his moan,

And knew his hunger as my own.

I saw at sea a great fog bank

Between two ships that struck and sank;

A thousand screams the heavens smote;

And every scream tore through my throat.

No hurt I did not feel, no death

That was not mine; mine each last breath

That, crying, met an answering cry

From the compassion that was I.

All suffering mine, and mine its rod;

Mine, pity like the pity of God.

Ah, awful weight! Infinity

Pressed down upon the finite Me!

My anguished spirit, like a bird,

Beating against my lips I heard;

Yet lay the weight so close about

There was no room for it without.

And so beneath the weight lay I

And suffered death, but could not die.

Long had I lain thus, craving death,

When quietly the earth beneath

Gave way, and inch by inch, so great

At last had grown the crushing weight,

Into the earth I sank till I

Full six feet under ground did lie,

And sank no more,—there is no weight

Can follow here, however great.

From off my breast I felt it roll,

And as it went my tortured soul

Burst forth and fled in such a gust

That all about me swirled the dust.

Deep in the earth I rested now.

Cool is its hand upon the brow

And soft its breast beneath the head

Of one who is so gladly dead.

And all at once, and over all

The pitying rain began to fall;

I lay and heard each pattering hoof

Upon my lowly, thatchèd roof,

And seemed to love the sound far more

Than ever I had done before.

For rain it hath a friendly sound

To one who’s six feet underground;

And scarce the friendly voice or face,

A grave is such a quiet place.

The rain, I said, is kind to come

And speak to me in my new home.

I would I were alive again

To kiss the fingers of the rain,

To drink into my eyes the shine

Of every slanting silver line,

To catch the freshened, fragrant breeze

From drenched and dripping apple-trees.

For soon the shower will be done,

And then the broad face of the sun

Will laugh above the rain-soaked earth

Until the world with answering mirth

Shakes joyously, and each round drop

Rolls, twinkling, from its grass-blade top.

How can I bear it, buried here,

While overhead the sky grows clear

And blue again after the storm?

O, multi-colored, multiform,

Belovèd beauty over me,

That I shall never, never see

Again! Spring-silver, autumn-gold,

That I shall never more behold!—

Sleeping your myriad magics through,

Close-sepulchred away from you!

O God, I cried, give me new birth,

And put me back upon the earth!

Upset each cloud’s gigantic gourd

And let the heavy rain, down-poured

In one big torrent, set me free,

Washing my grave away from me!

I ceased; and through the breathless hush

That answered me, the far-off rush

Of herald wings came whispering

Like music down the vibrant string

Of my ascending prayer, and—crash!

Before the wild wind’s whistling lash

The startled storm-clouds reared on high

And plunged in terror down the sky!

And the big rain in one black wave

Fell from the sky and struck my grave.

I know not how such things can be;

I only know there came to me

A fragrance such as never clings

To aught save happy living things;

A sound as of some joyous elf

Singing sweet songs to please himself,

And, through and over everything,

A sense of glad awakening.

The grass, a-tiptoe at my ear,

Whispering to me I could hear;

I felt the rain’s cool finger-tips

Brushed tenderly across my lips,

Laid gently on my sealèd sight,

And all at once the heavy night

Fell from my eyes and I could see,—

A drenched and dripping apple-tree,

A last long line of silver rain,

A sky grown clear and blue again.

And as I looked a quickening gust

Of wind blew up to me and thrust

Into my face a miracle

Of orchard-breath, and with the smell,—

I know not how such things can be!—

I breathed my soul back into me.

Ah! Up then from the ground sprang I

And hailed the earth with such a cry

As is not heard save from a man

Who has been dead, and lives again.

About the trees my arms I wound;

Like one gone mad I hugged the ground;

I raised my quivering arms on high;

I laughed and laughed into the sky,

Till at my throat a strangling sob

Caught fiercely, and a great heart-throb

Sent instant tears into my eyes;

O God, I cried, no dark disguise

Can e’er hereafter hide from me

Thy radiant identity!

Thou canst not move across the grass

But my quick eyes will see Thee pass,

Nor speak, however silently,

But my hushed voice will answer Thee.

I know the path that tells Thy way

Through the cool eve of every day;

God, I can push the grass apart

And lay my finger on Thy heart!

The world stands out on either side

No wider than the heart is wide;

Above the world is stretched the sky,—

No higher than the soul is high.

The heart can push the sea and land

Farther away on either hand;

The soul can split the sky in two,

And let the face of God shine through.

But East and West will pinch the heart

That can not keep them pushed apart;

And he whose soul is flat—the sky

Will cave in on him by and by.

Commentary on "Renascence"

The poem "Renascence" launched the career of Edna St. Vincent Millay and has since been widely anthologized.

First Movement: Simply Observing Nature

The first movement describes an experience that had an impact on the speaker. She begins quite casually by reporting that all she could see from her present vantage point were mountains and a wooded area as she looked in one direction.

And after as she turned her head to see what else the landscape offered, she saw a bay in which three islands stood. The experience of simply observing nature turns mystical as the speaker continues to describe events that occur during her observation.

She says that the sky is so big but that it must end somewhere, and then she exclaims that she can actually view the top of the sky!

The speaker decides that she can touch the sky with her hand, and then she tries and discovers that she could "touch the sky." The experience made her scream, being so unexpected and unusual. It then seemed to her that the entire universal infinite body descended and covered her own being.

She then repeats her exclamation that the "awful weight" of Infinity was pressing her down. She refers to herself "finite Me," drawing the distinction between her little self and the Infinite Self. With this unusual event came the ability to see people and events happening in other parts of the world.

She seemed to have a supernatural ability to know what other people are experiencing. She is startled by this experience and closes the movement claiming that she has endured death from the weight of Infinity covering her, yet she "could not die."

Second and Third Movements: A Unique Mystical Experience

In the second movement, the speaker descends into the earth, yet not as one deceased but as one very much alive, feeling her soul leave her body. She feels that infinite weight lift off and her "tortured soul" is able to burst from its confines, leaving in its wake swirling dust.

In the third movement, the speaker feels weightless as she lies still listening to the rain, which she describes as friendly since there is no other friendly voice or face for her to encounter: "A grave is such a quiet place."

Fourth Movement: Desire for Rebirth

In the fourth movement, the title of the poem is realized, as "renascence" means "new birth"; the speaker realizes that if she remains six-feet under in a grave, she will not be able to experience the beauty of the sun coming out after the rain.

She wants to be able experience the gentle breezes that waft through "drenched and dripping apple-trees."

The speaker also realizes that she will never again observe the beauty of spring as silver and fall as gold. And so she cries out desperately to her Belovèd Creator for a new birth. She begs to be placed back on earth, as she implore God to wash away her grave.

Fifth Movement: An Answered Prayer

The speaker's prayer is answered. She has great difficulty explaining such a miracle as she asserts that she cannot explain how such an event occurred, but she only knows that it happened to her, and she is quite convinced of its reality and importance.

The speaker is once more capable of seeing the beauty of the rain subsiding, and she repeats that fascinating image of the drenched and dripping apple-tree: "And all at once the heavy night / Fell from my eyes and I could see, / A drenched and dripping apple-tree."

The speaker's exuberance over her new birth causes her to hug the trees, to hug the ground as she laughs and cries tears of joy and gratitude. Her new birth has brought her an awareness that she had not known before.

She cries out to God that henceforth she will never doubt the efficacy and power of her Divine Belovèd, whom she describes as "radiant identity." The speaker feels now that she realizes the Divine who pervades all of nature.

Sixth Movement: Spiritual Understanding

The sixth movement dramatizes the spiritual understanding gained by the speaker through her new birth; she has been born again, and now she understands the width of the heart.

Edna St. Vincent Millay's Precocious Insight

Edna's mother encouraged her to submit her poem, "Renaissance," the original title of the work, to a poetry contest. The purpose of the contest was to gather poems for publication in The Lyric Year, an annual poetry anthology.

The poem took only fourth place; however, the brilliance of the work caused embarrassment to those whose pieces were judged above Millay's.

It was obvious to those entrants that Millay's piece was a far more first-place worthy poem. But the poem brought Millay's talent to the attention of Caroline Dow, who directed the New York YWCA National Training School; Dow then paid for Millay to attend Vassar.

Millay was only twenty-years-old when she wrote "Renascence." Such insight is rare in one so young. One can only wonder at such precocity in poetic talent.

Commentary on Edna St. Vincent Millay Poems

- Edna St. Vincent Millay's Sonnet I "Thou art not lovelier than lilacs,—no" Edna St. Vincent Millay's speaker in sonnet I "Thou art not lovelier than lilacs,—no" uses rich irony and alludes to the King Mithradites legend to assuage her overwhelming passion for beauty.

- Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Renascence" Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Renascence" dramatizes a mystical experience that results in the speaker's new birth, realizing the depth of love and the power of the soul.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Linda Sue Grimes