The Amazing English Language

English Quirks

Author Stephen Fry says, “The English language is like London: proudly barbaric yet deeply civilized, too, common yet royal, vulgar yet processional, sacred yet profane.” Herewith, a loving journey into some of the quirks and complexities of the language.

Orphaned Negatives

Many positive words have prefixes that make them negative. Examples include possible becoming impossible or inherited being turned into disinherited. But, some positive words do not have a negative partner; they are called orphaned negatives, and people sometimes have fun with them.

In his 1938 novel, The Code of the Woosters, P.G. Wodehouse has a character say, “I could see that, if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.”

More recently, comedian Sara Pascoe pulled a naughty on the BBC program Quite Interesting. Orphaned negatives were under discussion and the word ineffable came up. Ms. Pascoe pointed to a slim, young man in the audience and said he was definitely effable.

Then, this being English in all its capricious glory, we have flammable and inflammable meaning the exact same thing.

Eggcorns

Merriam-Webster tells us that an eggcorn is “a word or phrase that sounds like and is mistakenly used in a seemingly logical or plausible way for another word or phrase.”

The word “eggcorn” comes from a mishearing of the word “acorn.” The word was created by the British linguist Geoffrey Pullum.

National Public Radio asked its listeners to send in their favourite eggcorns. They did not disappoint, delivering thousands. Here is a tiny sample:

- “genetic brands” instead of “generic brands;”

- “mute point” instead of “moot point;”

- “illicit a response" instead of “elicit a response;”

- “old-timers disease” instead of “Alzheimer's disease;” and,

- “flush out" instead of “flesh out.”

Antigrams

The fiends that compile cryptic crosswords are fond of driving their readers squirly by hiding solutions in anagrams; words and phrases created by rearranging the letters of other words.

But some people like to make a bigger challenge; they like to create a new word or phrase from the old one that is the opposite of the source.

Not for them productive evenings reducing the oversupply of Chardonnay or getting to the next level of Angry Birds; these folk waste their time manoeuvring letters into new forms, so that “the winter gales” becomes “sweltering heat.”

Some other examples:

“Funeral” can be “real fun;”

“A volunteer fireman” is turned into “I never run to a flame;” and,

Anybody who has worked in retail will appreciate that you can change “customer” into “store scum.”

Aptronyms

In my home town there was a man called William Brick; he was, of course, a builder. His name matched his occupation, an occurrence that is called an aptronym or, if you want to go all fancy-pants, you can call it nominative determinism.

This gives rise to a hypothesis put forward by psychiatrist Carl Jung that people are unwittingly drawn to character traits and jobs that reflect their names.

There is ample proof that this is so. For example, my name is Taylor, so, of course, I am a writer. My wife's maiden name was Nadeau so she too is a writer. Our two Taylor children are in information technology support and social work.

Maybe Dr. Jung had some better ideas.

We probably have to thank newspaper columnist Franklin P. Adams for the word aptronym. He started with patronym (the taking of a father's name), worked out an anagram of the first syllable feeling that “apt” was appropriate for his purpose.

Richard Nordquist at thoughtco.com gives us a few examples of aptronyms:

“There is an ornithologist called Bird, a pediatrician called Babey, and a scientist specializing in animal bioacoustics called Dolphin.”

However, he doesn't mention Jaime Sin who became a cardinal. Yep, Cardinal Sin. An example of what's known as an inaptronym. There are others: Samuel Foote was an English actor who lost a leg in an accident, and Rob Banks is a British police officer.

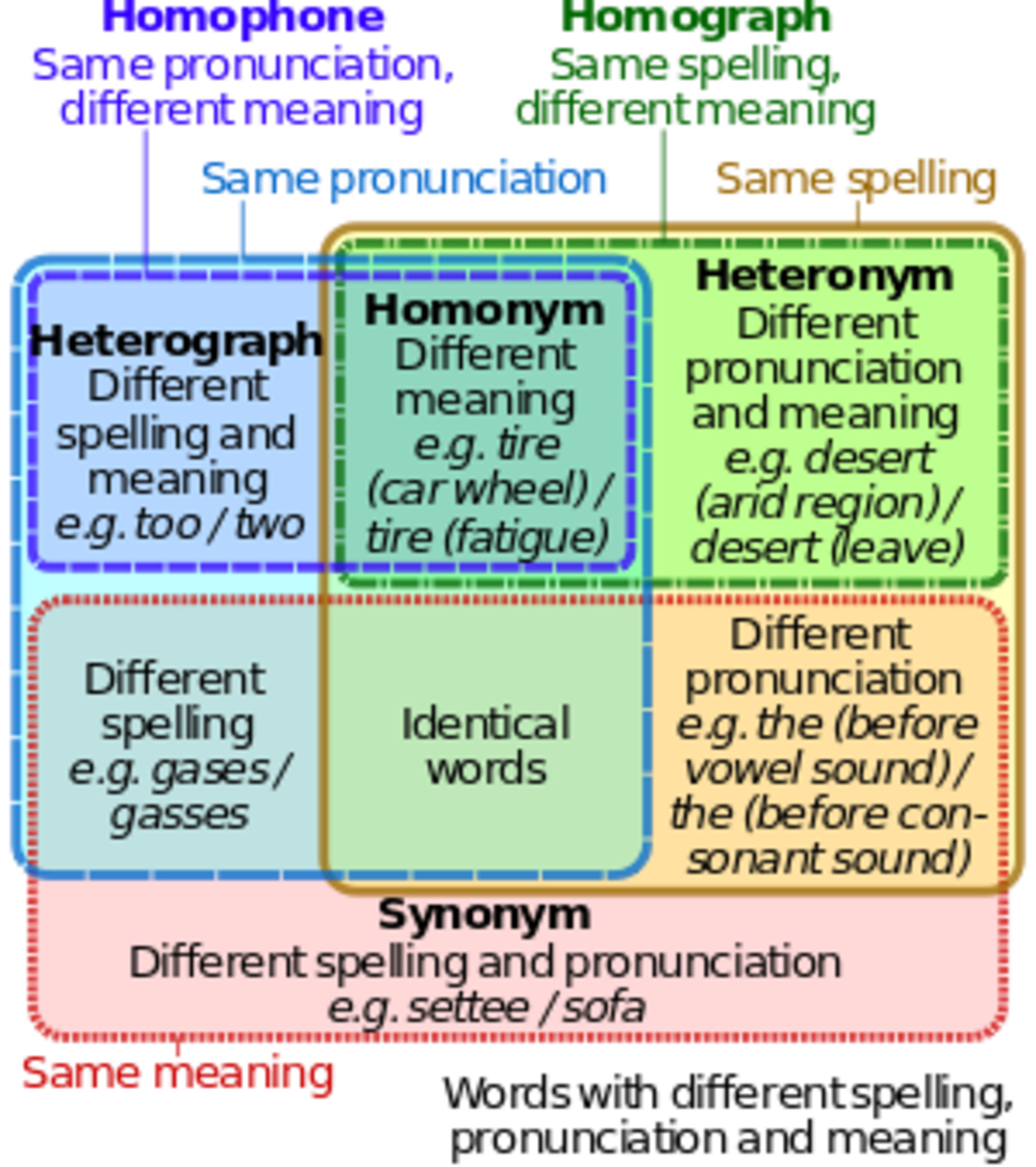

Homographs, Homophones, and Homonyms

Many words in English are spelled the same but have different meanings; they are called homographs. Likewise, homophones sound the same and are spelled differently.

The mischievous rascals include such things as “there, their, and they're,” and also “your, you're, yore, and yaw.” They lurk in the darker reaches of the minds of writers ready to leap out into the open immediately after the “Send” button has been pressed.

Herewith, a couple of homographs:

“I will lead you to where the lead pipe needs repairing.”

“She gave a bow after tying an intricate bow.”

And now, two homophones:

“From the beach you can see the sea.”

“I ate eight hot dogs.”

Together, these homographs and homophones are called homonyms. No they are not yells a cohort of grammarians that claims a homonym must be both at the same time:

“The baseball pitcher was thirsty, so he drank a pitcher of lemonade.”

It's around issues such as these that university tenure might hang in the balance.

Neologisms

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) says that roughly 1,000 new English words, called neologisms, are added to its database every year. Some recent additions include:

- sglods, n.: “Small pieces of potato (typically sticks or batons) fried or otherwise cooked in oil and eaten hot ...

- cyberstalk, v.: “transitive. To intimidate or harass (a person) online by persistently sending messages or images of an obsessive, threatening, or offensive nature…

- ghost gun, n.: “A firearm that is not registered or trackable; esp. one that has been assembled or manufactured by the owner, particularly using 3D printing.

- degenerationism, n.: “A theory or belief that humans have a tendency to degenerate or decline physically, mentally, or morally as they evolve…”

Here are some other neologisms that have been created by a man who says he has the “best words.” They have not, as yet, been included in the OED:

- Bigly;

- Covfefe;

- Nambia; and,

- Unpresidential.

We began with a quotation, so let's finish this up with some words from newspaper columnist Doug Larson: “If the English language made any sense, lackadaisical would have something to do with a shortage of flowers.”

Bonus Factoids

- The word neologism occurs 0.4 times in every one million words in English.

- A mondegreen is similar to an eggcorn but is used to describe the mishearing of a lyric or poem. You can read more about this here.

- Prefixes go in front of words to change their meaning, so healthy becomes unhealthy. Suffixes do the same job at the end of words. Infixes are inserted into words or phrases. An often heard cousin of the infix is the expletive infixation. An example occurred among lads who shunned education in the village in which I grew up. So, Castle Bytham became Castle Freaking Bytham The added infix was not “freaking” but something quite similar.

- The origin of the “ough” string of letters is a mystery. Some say it's Germanic, others that it's Celtic. There's a similar disagreement about pronunciations; some say there are eight, others that it's ten.

Sources

- “A Gruntled Look at Orphan Negatives.” Stephen Liddell, stephenliddell.co.uk, March 17, 2021.

- “Here Are 100 'Eggcorns' That We Say Pass Mustard.” Mark Memmott, NPR, June 1, 2015.

- “Aptronym Names.” Richard Nordquist, thoughtco.com, July 24, 2019.

- “Antigrams: Definition and Examples.” iluenglish.com, undated.

- “What’s the Difference Between Homophones, Homographs, and Homonyms?” Gina Rancaño, languagetool.org, June 16, 2025.

- “New Word Entries.” Oxford English Dictionary, September 2024.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2025 Rupert Taylor