Causes of the Financial Crisis: A Series of Bad Decisions

The financial crisis that began in 2008 was caused by a collection of bad decisions. Greed on Wall-Street, lack of government supervision, and bad financial decisions by consumers nationwide led to the biggest collapse since the Great Depression. This is a general overview of some of the factors that led to the meltdown and what can be learned from the choices that were made during the time.

Securitization and Asset Backed Securities

Many government regulators stated that one of the causes of the crisis was the fact that banks were so highly leveraged. In some cases leverage ratios reached 33:1. While this may have not helped the situation, it was not the root cause of what happened. In William Cohan’s article “How we Got the Crash Wrong”, he states that although Wall Street firms were highly leveraged in 08’, they have always been highly leveraged. There have been times of legitimate economic prosperity wherein firms have been leveraged to similar ratios.

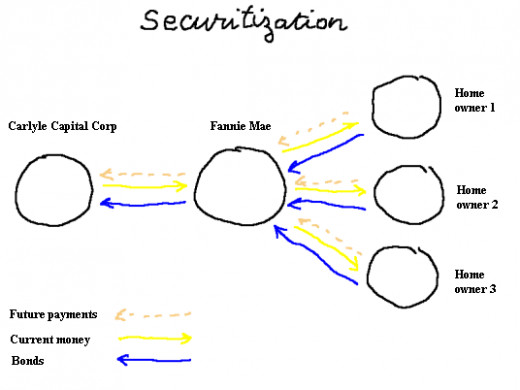

The root cause was the bundling of bad mortgages and other loan products into securities that were sold by large investment firms such as Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns. These companies would buy mortgages, bundle them, and in turn sell them as securities in the open market to interested investors in order to obtain more capital to buy more loans from banks. The banks giving mortgages were making more money with the more loans they made. Investment companies were making more money off selling investments in the open market. Profits were beginning to reach record levels.

The way investment firms securitized was by buying bundling multiple mortgages which had similar interest rates and characteristics. There were also other assets that were made into securities including auto loans, student loans and credit card debts. These companies would buy and sell these to investors who were led into thinking the securities were safe and secure investments. This would not have proven to be such a disaster if credit rating agencies would have rated the securities being offered with caution and accuracy. They did not. Many checks were written by large Wall Street institutions to the agencies in order to ensure their product offerings were rated highly.

The fact is most of the mortgages that had been bundled, sold, and resold were bound for default. Lucrative adjustable rate mortgages with teaser intro rates caused many to accept large loans they would not be able to pay for. After a couple years or less of a low rate, these rates “adjusted” and mortgage payment requirements began to rise because of the increased interest rate. Defaults began to spread like wildfires and housing prices began to plummet. Banks did not receive payment for the loans they still held as assets, the value of the securities investment firms had sold plummeted and their clients refused to hold them. The value of these companies like fell drastically.

Credit Default Swaps

Many banks chose to obtain a form of insurance for the assets they still had on their books. These became known as credit default swaps. In this process, a bank will make a series of payments to a company willing to sell them a credit default swap. Companies like AIG (among many others) would offer a form of insurance for the mortgages or other assets the banks held. This transferred the risk of default from the bank to the shoulders of the company selling the insurance. Once again, the true value and risk of the mortgages was overlooked. The perversion of incentives became a major factor. If an employee could sell a credit default swap to a bank, he would be rewarded with monetary bonuses, regardless of the risk involved. Banks wanted less risk and thus were buying as many default swaps as they could. The entire system would eventually collapse. As people began defaulting, companies like AIG were not prepared. They were unable to pay for the amount of defaults they had bet on, and banks received no payment from these firms or their borrowers.

Here again, profits for Wall Street firms skyrocketed to record levels. The more CDS they could had out, the more fees they receive from the institutions offering the loans. Hundreds of millions of dollars were made by most of these firms for the decade leading up to the crises.

Richard Fuld, former CEO of Lehman Brothers, made over $485 million from 2000 to 2008.

Governmental Regulation

Government’s role in bringing about the crises has been underestimated and certainly is a major factor in the causes of the collapse.

As Cohan points out in his article, “The SEC did two things in 2004: First, it assumed the added responsibility of regulating Wall Street’s larger holding companies—as opposed to just the broker-dealer subsidiaries within them. That’s where more and more funky and risky assets, such as derivatives and mortgages, had been housed over the years. Second, the SEC required the holding companies to report their capital adequacy in a way that was consistent with international standards, and to discount their assets for market, credit, and operational risks. Clearly, the SEC did a poor job of monitoring Wall Street once it obtained this increased regulatory authority.”

The Federal Reserve and SEC either did not foresee the collapse of financial institutions, or chose to ignore it because of the economic prosperity being realized in the years leading up the crises. Who wants to stop a party that seems as though it will never end? Perhaps the problem was the fact that many of the financial leaders and regulators served on the boards of many large investment companies. For example, Hank Paulson (Former Treasury Secretary) previously had made half a million dollars on the board of Goldman Sachs before accepting the role of Treasury Secretary.

But government’s role was even more evident when it began encouraging buyers to purchase homes. The idea set forth was that “any person could have just as nice of a house as the next man.” If the government tells people they can afford something, who can possibly argue they cannot?

Many argue that government was just as responsible for the failures of the financial institutions as their own leaders were. The legitimacy of the claim is up for debate. Still, the 2004 actions taken by the SEC played a critical role in letting Wall Street off its leash. It allowed them to step into the arena of riskier and riskier lending practices and unregulated trading activities with derivatives

Lessons to be Learned

While these are just a couple of the complicated reasons which led to the downward spiral of the global economy in the crisis, they are usually considered the main reasons for the crash. Many economists have debated and argued over the main reasons of the crisis, and even they cannot agree what the trigger for it all was. If economists and financial professionals cannot agree on these matters, how is the general public expected to know what decisions they can make with confidence and which companies to trust?

Well, people can start by remembering a simple rule. Do not spend above your means. Just because a financial institution or government tells us that we can afford a house that cost the equivalent of ten times our yearly salary, doesn’t mean we should take their advice. Financial companies are out to make a profit. It is why they exist at all. While many are legitimate intermediaries and will not take on such high risk, many will. We must consider our own personal situations and not reach for something that seems too good to be true. As we have learned from the financial meltdown, it usually is.

Investors must learn to do their own due diligence. People who were vested in many of these financial firms lost savings and large accounts because of the collapse. Complicated financial securities which we do not understand should not be bought until we understand them. If we do understand them and they seem too speculative, we should not take the risk.

Firms like Lehman and AIG should have placed the risk on their executives and decision makers, not the American people. While many home buyers made poor decisions, it was companies such as these which encouraged such spending. If incentives were not as perverse, and companies were forced to put the net worth of their executives on the line, such risky choices would not be made. This is the way financial firms used to operate. People used to live their own personal American dream based on their own means. That ideology has since been twisted by people telling us we can have more than what we currently do. We must venture back to the days of old and use practices put forth by institutions that had their client’s interest at the heart of decision making, who put their own personal wealth on the line with every risk they took on.

Government must better forecast and regulate lending and complicated financial practices. If we have not learned that from the recent crisis, then we never will. If lobbyists have the ability to persuade congressmen and lawmakers to allow financial firms to do as they please, then the American people really do not have a say in the matter. The government must not be run by Wall Street anymore.

The economic prosperity of the American people must be the focal point of business, not greed.