The Basics of Stock Options

Calls and Puts

Some of you reading this may already know this definition, but for the benefit of those who may not be familiar with options: An option is a contract that gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying instrument at a specific price on or before a specific date.

The underlying instrument may be a stock, future, currency, interest rate, index, commodity, piece of real estate, the list goes on. For the purposes of simplicity, we will limit the discussion to stock options, or options where the underlying security is a listed stock trading on one (or more) of the major exchanges (NYSE, PHLX, NASDAQ, etc.) Even though we will focus on stock options, the same principles outlined are applicable to the other underlying securities mentioned previously.

There are two types of options: calls and puts. A call gives the buyer of the option the right, but not the obligation, to buy 100 shares of the underlying stock on or before the expiration date at a specific price known as the strike price, exercise price, or simply the 'strike'. A put gives the buyer of the option the right, but not the obligation, to sell 100 shares of the underlying stock at the strike price of the option.

Let's say XYZ is trading at $49 and your research indicates that the stock has a good chance of trading into the upper 50's between now and the end of June. In order to profit from this increase in the stock's value, you decide to buy an XYZ June 50 call. As the buyer of an XYZ June 50 call, you have purchased the right to buy 100 shares of XYZ at $50 per share between now and the day the option expires (the Saturday following the 3rd Friday of the expiration month). No matter where the stock goes between the time you purchase the call option and the day it expires, you have locked in the right to purchase 100 shares of XYZ at $50 per share. If it goes to 55, 60, 65, or higher, you still have the right to buy 100 shares at $50 per share.

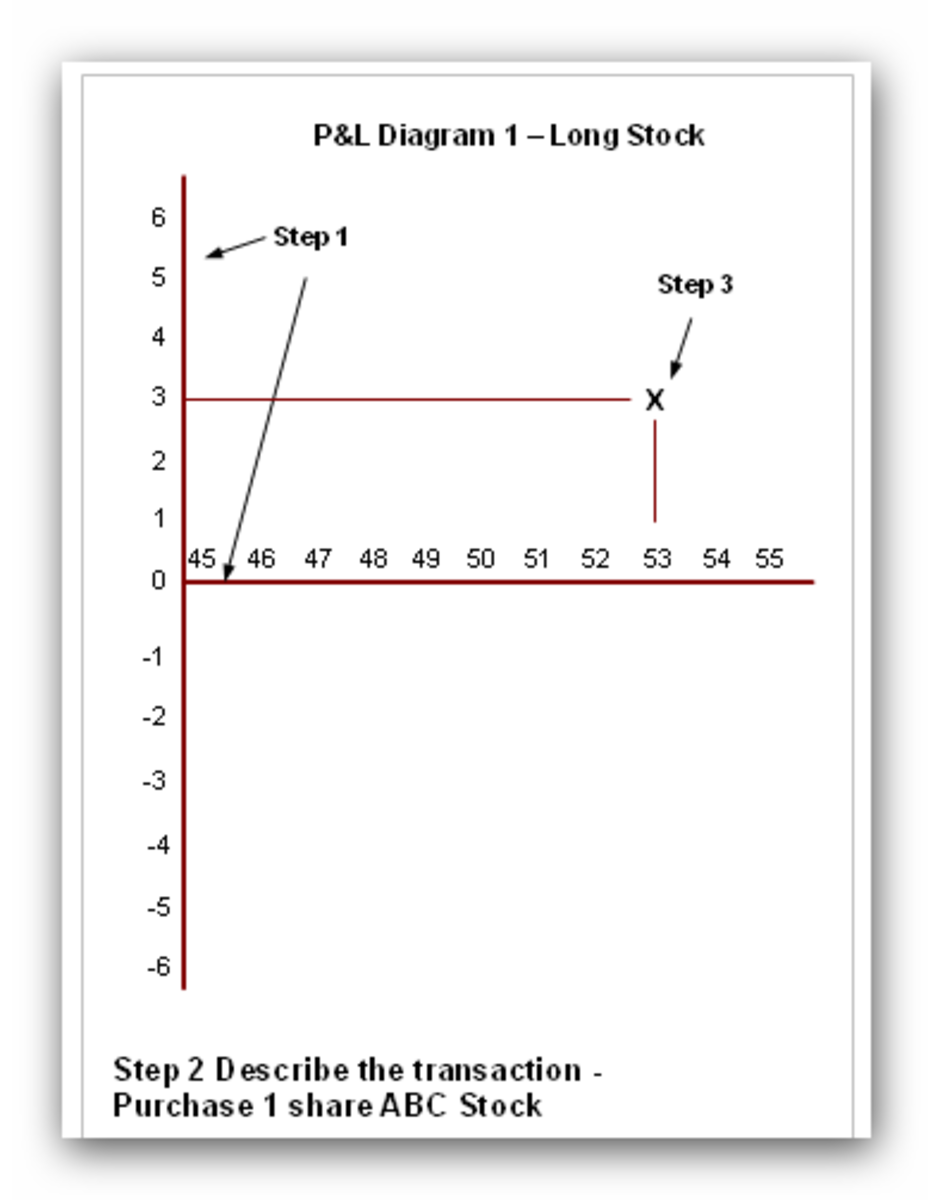

In this example the price (premium) of the June 50 call is $3. It will cost you $300 to buy one XYZ June 50 call. The $300 is calculated by taking the option premium ($3) and multiplying it by 100 (the number of shares on which you have purchased to right to buy at $50). If, as you predicted, the stock moves up and is trading at say, $57 per share on the day the option expires, your $50 call option is now worth at least $7. This is the intrinsic value of the $50 call. You can sell this option for $7 (total premium of $700) and realize a profit of $400 (minus transaction costs). You can also exercise the option and purchase 100 shares of the stock at $50 even though it is currently trading at $57. This is the right you acquired when you purchased the option.

If you were incorrect, and the stock closes at $50 or below, you only lose the $300 you paid for the option. Your break-even point at expiration is a stock price of $53. This is the strike price of the option ($50) plus the option premium ($3). Transaction costs and the bid/ask spread will skew this slightly.

Take these same principles and apply them to the purchase of a put option. Remember, the put gives the holder of the option the right to sell 100 shares of the underlying security. Suppose you are really bearish on a stock after doing your due diligence and you want to profit from a downward move in the stock. Yes. Put options allow you to make money when the price of a stock falls. How cool is that?! The stock is trading at $35 per share, and you think it is going to drop into the mid 20's. You can purchase a put option that will allow you to sell 100 shares of the stock at the strike price of the put. You purchase an XYZ June 30 put for $2 (the option premium). This will cost you $200 per option (option premium of $2 x 100 shares). No matter where the stock trades from the time you buy the put until it expires, you have the right to sell 100 shares of XYZ at 30.

Assume you were correct on the direction of the stock and it is trading at 26 at expiration. Your June 30 put, for which you paid $2, is now worth at least $4. The intrinsic value or the amount by which the option is "in the money" is $4. You can sell the option for $4, thereby doubling your investment. Your break-even point on the put purchase is the strike price ($30) minus the premium paid ($2) which is $28. This is the level to which the stock must fall on the day of expiration in order for you to break even on the purchase of your put option. Anything below $28 and you are in profit territory.

Before the advent of put options, one had to sell a stock short (selling it without owning the shares in the hope that the price would fall and the short seller would be able to buy the shares back at a lower price from where they sold it) in order to profit from a downward move. Needless to say, there is tremendous risk in short selling. If the stock gaps up; you are looking at some potentially major losses that you can't truly quantify at the time you make the short sale. By purchasing the put option, you have limited your potential loss to the price you paid for the option ($200) if you happen to be wrong about the direction the stock will take during the lifespan of the put option you bought. If the stock goes to 36 instead of 26, the maximum you can lose is $200 since this is all you paid for the put.

This is a very generic primer on some option basics. Some terminology such as "intrinsic value" and "in the money" were interspersed throughout this lesson. Please continue to follow my series on options where I will elaborate and put a finer point on the basics discussed here in addition to exploring more advanced topics relating to options, investing, and finance in general.