Witches: Prejudice and Misconceptions

Day #11 of my "30 Hubs in 30 Days" Challenge

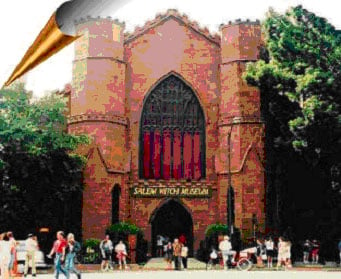

The castle-like building stands on a historical lot across from the town common. The famous Witch Museum-- the center for knowledge about a series of tragic events that occurred in 1692-- in Salem, Massachusetts. The building is as mysterious as its subject matter. It looms over its visitors, and it is easy to imagine stereotypical witches brewing spells inside its two towers. An enormous arch-shaped window dominates the front of the building. It is covered with intricate black metal paneling and red curtains, which make it appear to be the blood-shot eye of a Cyclops. Immediately below it is a smaller arch that serves as a gate into the building. The doors are open wide, but it is impossible to see anything through the dark, cave-like opening, and the interior is a mystery. Large trees stand, like sentries, on either side of the door. Their size implies age. The building’s ancient appearance contrasts with the modern clothing of the tourists that walk in and around it. Why are they here? It has been more than three hundred years; what is it about witches that continues to hold their fascination?

It is ironic that the witchcraft that the seventeenth century residents were so afraid of now draws the curiosity of tourists, such as myself, from across the country. Perhaps it is the idea of witches that appeals to us. After all, what is a witch? Is there such a thing a witch? If there is, how can we tell the difference between a witch and a “normal” person? Are they dangerous? These are just a few of the many questions that the Salem Witch Museum has attempted to address, and many of them deal with the stereotypes and misconceptions that people have about witches. They argue that the “file definition of the word [witch] has changed as our beliefs and customs have evolved” (D’Amario). Initially, it referred to a Celtic midwife. The stereotype of “a hag dressed in black with pointed hat and green face... [flying] across the moon on her broom” was begun by Catholic Church leaders during the middle ages in an attempt to end pagan worship. They labeled witches “evil troublemakers” (D’Amario).

The previous image depicts the standard stereotype. Under some circumstances, this image doesn’t appear to be a bad thing. For instance, if your daughter decided to dress up as a witch for Halloween, then this costume would be great. Anyone that saw her would know that she was only pretending, and no one would take her seriously if she was to announce, “I’m a witch!” However, under different circumstances, during 1692 in Salem, having a child announce that someone was a witch had a completely different outcome:

The problem with stereotypes is that they lead to prejudice and ignorance, which were both key factors in the Salem Witch Trials. The crisis began during February when two young girls became ill, and, as a result, began to behave strangely. Their parents consulted doctors, but after failing “to discover the physical cause for the symptoms and dreadful behavior, [the] physicians concluded that the girls were under the influence of Satan” (“Trials”). To the modern reader this diagnosis sounds crazy. However, medicine at the time was primitive, and the people involved were Puritans. Religion was a huge part of their lives, and they usually contrived spiritual explanations for the things that they could not otherwise explain. In addition, one of the girls involved was the minister’s daughter. It is interesting to note that initially the people accused of witchcraft were social outcasts. For instance, Tituba was the minister’s slave, Sarah Good was “a beggar and social misfit,” and Sarah Osborne was an “old, quarrelsome” woman who no longer attended church (Linder).

Returning to my earlier question, how can you tell the difference between a witch and a “normal” person? This is an impossible question to answer, but it was what that the jurors were faced with. Between March and September many people were accused, tried, and executed for witchcraft based upon “intangible evidence” such as “confessions, supernatural attributions (such as ‘witchmarks’) ... reactions from the afflicted girls... [and] spectral evidence” (“Trials”).

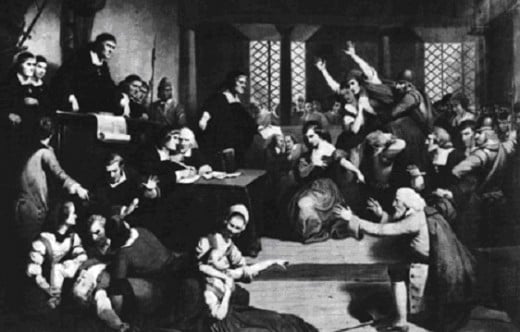

As this painting depicts, the events within the courtroom were crowded and confused. There is a lot going on-- girls are having fits, others are pointing fingers, people are fainting, and a man is pleading on his knees in front of the jurors. The room is packed with people and even more are crowded around the window outside. The scene is depicted in black and white, which is appropriate because it reflects the Puritans’ way of thinking. A person was either a follower of “God” or a worshiper of “Satan.” There are several people pointing or reaching out. If we follow the picture clockwise from the top, the directions that the arms are extended come full circle. This is also appropriate because in the end, they were all at fault. They all played a part in the tragedy.

This painting reminds me of a similar trial in the movie, “The Monty Python and the Search for the Holy Grail.” A mob of villagers approached their leader with a woman that they claimed was a witch. When he asked them how they knew she was a witch, they replied that she looked like one. After some questioning, the villagers confessed to dressing her up as a witch-- complete with a black pointed hat and a carrot for a nose. When asked for further evidence, one villager pointed out that she had a wart and another declared, “She turned me into a newt!” When this was questioned, he hesitantly replied, “I got better...” Finally, their leader announced that “there are ways of telling whether she is a witch.” His logic was this: we burn witches, so what else do we burn? Wood. “Why do witches burn?” They’re made of wood, and wood floats. “What also floats?” Ducks. Therefore (“logically”), “if she weighs the same as a duck... she’s made of wood... [and therefore] a witch!” (“Witch”). Although, the logic used within the Salem courtroom wasn’t quite this ridiculous, there are similarities between their methods of finding “proof” that the accused were witches.

Monty Python "She's a witch!" Scene from "Search for the Holy Grail"

It has been more than three hundred years since the events in Salem took place, but witches have remained a popular subject for books, movies, and television. Although there have been different approaches to the topic, the majority of the time witches are still looked down upon. Even within the world of Harry Potter, they are unable to avoid prejudice. When Harry first discovered that he was a wizard, he confronted the aunt and uncle that raised him. His aunt replied, “Knew ! Of course we knew! How could you not be, my dratted sister being what she was? ... a freak! ... of course I knew you’d be just the same, just as strange, just as-- as-- abnormal ...” (Rowling 53). Harry Potter has also been the subject of prejudice outside of the books he appears in. The series has been banned by numerous churches, as well as some book stores and libraries. Why should a series of fictional children’s books be banned? Because the books are about witches, and the people that ban them believe the stereotypes about them.

In their attempt to eliminate the stereotypes about witches, the Salem Witch Museum has made information available about contemporary witchcraft (which includes Wicca):

“it is... a pantheistic religion that includes reverence to nature, belief in the rights of others and pride in one’s own spirituality... [they] focus on the good and positive in life and in the spirit and entirely reject any connection with the devil.” (D’Amario)

They are not evil troublemakers, and they are not dangerous. However, they are “anxious to dispel” the misconceptions that people have about them. Perhaps, if the people of Salem had been more open minded and less judgmental, they would not have been so quick to blame members of their community for the girl’s illness. Instead, they acted upon their prejudices and behaved rashly. They didn’t begin to question their actions until after the witch hunts had gotten out of control. Although the entire ordeal lasted less than a year, nineteen people had been convicted and executed for witchcraft, a man had been “pressed to death” after he refused to be tried, and many others became ill and/or died in prison (D’Amario). The Salem Jurors later wrote a formal “Declaration of Regret” for their role in the tragedy:

... we confess that we were not capable to understand... we fear we have been instrumental... though ignorantly and unwittingly, to bring upon ourselves ... the guilt of innocent blood... we would none of us do such things again... (“Accused”)

Sadly, their regret and acknowledgement of their ignorance regarding witchcraft came too late. It was too late to help the nineteen people that they had sentenced to death. However, it is not too late to learn a lesson from this experience: rash, prejudiced behavior often leads to regret.

Works Cited

“Accused of Witchcraft.” Notable Women Ancestors-- Witches. 18 Oct 2004 <http://www.rootsweb.com/~nwa/witch.html>.

D’Amario, Alison. “Salem Witch Museum Education.” Salem Witch Museum.Com. 19 Oct 2004 <http://www.salemwitchmuseum.com/education.html>.

Linder, Douglas. “Account of the Events in Salem, An.” An Account of the Salem Witchcraft Investigations, Trials, and Aftermath. 18 Oct 2004 <http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/salem/SAL_ACCT.HTM>.

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. New York: Scholastic, 1997.

Salem Witch Museum, The. Salem: Salem Witch Museum, 1995.

“Salem Witch Trials 1692: A Chronology of Events.” Salem Witch Trials Chronology. 18 Oct 2004 <http://www.salemweb.com/memorial/>.

“Witch, The.” Monty Python’s Completely Useless Web Site. 02 Nov 2004 http://www.intriguing.com/mp/_scripts/witch.txt.