Does Abortion Reduce Crime?

Going Where the Data Leads You

A while ago, I was watching the movie “Freakonomics” on Netflix, which is currently our family’s only means of watching television. As the title indicates, Freakonomics is a movie (based on a book) created by two guys who take an unconventional approach toward economics. I first became familiar with them because one of the co-authors / founders is a frequent guest on the NPR show “Marketplace.” So they study issues that are often not considered to be in the traditional realm of economics, find connections between events and forces that are not usually associated with one another, and often draw conclusions that seem at first to be counterintuitive and are often controversial. The recurring theme of the book/movie/podcast/blog is to follow the data wherever it may lead.

The movie consists of a few mini-documentaries that are representative of the kind of research conducted by the Freakonomics team, and it was not hard to figure out which of their studies would generate the most controversy. Steven Levitt – the trained economist of the two – set out to determine why crime rates have consistently been dropping since the early 1990’s. He mentions several factors that may have played some part, including new policing techniques, tougher sentencing of criminals, changes in the illegal drug market, and economic growth. And while he acknowledges that these factors have played some part, by his estimation, they only account for about half of the drop in crime.

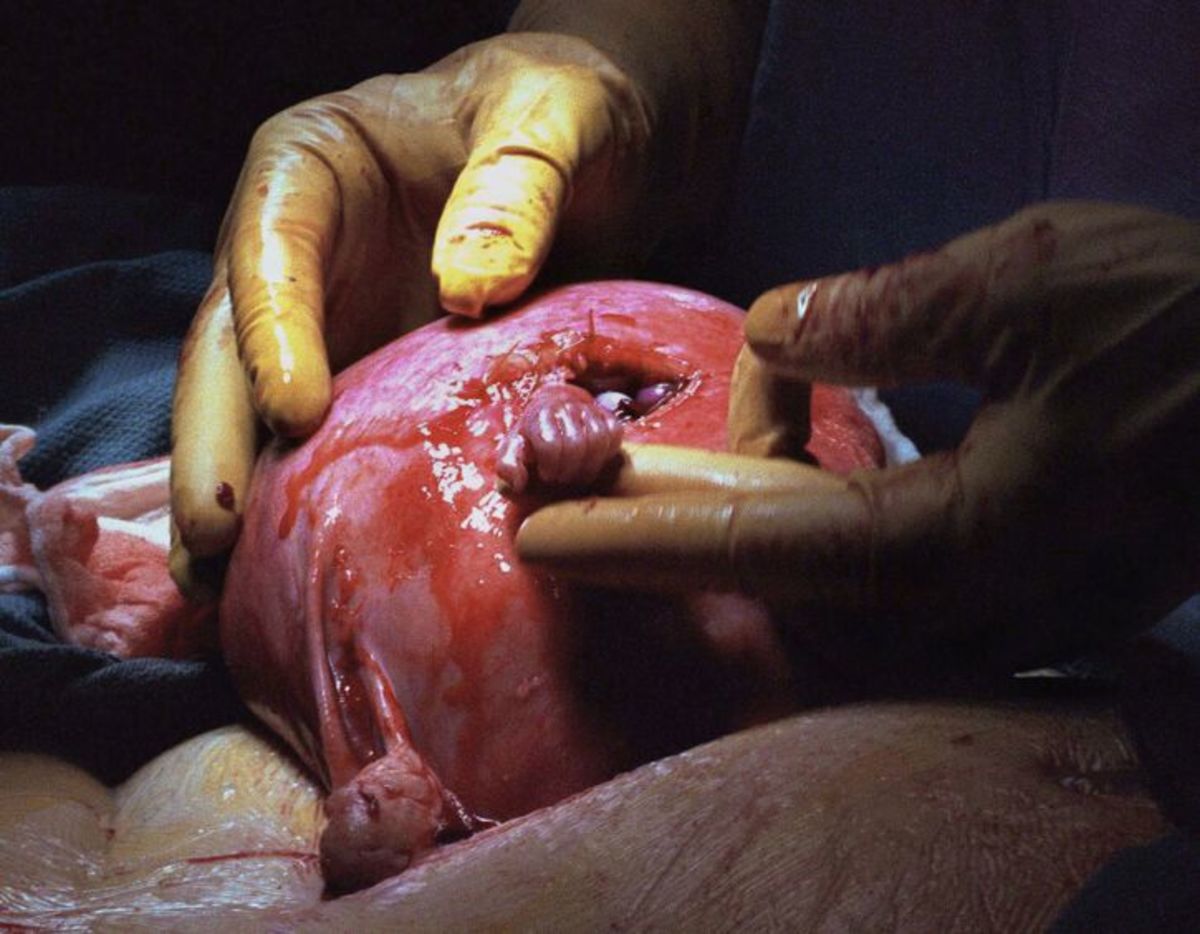

He then proceeds to drop the bombshell. If you do the math, the first generation of Americans to be impacted by the legalization of abortion in 1973 were becoming teenagers in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. Since this is the age at which some people will typically begin turning to crime, the early 1990’s would also be the era in which the impact of legalized abortion on crime rates would begin to be seen. And even more striking is the fact that in states where abortion was legalized before 1973, crime rates started to drop even sooner. So if unwanted children are more likely to turn to crime when they reach adulthood, it is plausible that crime rates will go down over the long term if you reduce the number of children who have parents who cannot (or will not) care for them very well.

Levitt does not go into enough detail during the movie to provide intricate details about the data that led him to this conclusion. So I am in no position to answer adequately the question posed in the title of this article. What primarily interest me, however, are the various reactions that people will predictably have to his conclusions. As the movie briefly addresses, many pro-life people are offended by the question itself. And anyone who would claim that abortion reduces crime is supposedly at best some sort of a pro-choice activist and at worst a supporter of eugenics. Is Levitt actually trying to argue that people from certain ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds more likely to produce criminals should abort their unborn children for the good of society? Should killing unborn children become a political policy for maintaining social order? Pro-choice people, on the other hand, might see Levitt’s data as one more argument to support their point of view. In addition to protecting a woman’s right to make decisions regarding her own body, legalized abortion has the added benefit of making us all safer.

But as Levitt points out in the film, his goal is not to promote a political policy agenda. The question of whether or not abortion reduces crime is not ultimately a political question or even an ethical question. Instead, it is a scientific question. The goal of an economist or any type of a scientist is to describe and explain phenomena as best he or she can. Then, once the scientific conclusions are made, people are free to draw ethical or political conclusions. The problem with what is often called science, however, is that people have drawn their conclusions before the data has been compiled. So instead of following the data where it may lead, they go looking for data that supports their conclusions. In some cases, people are aware that they are looking for information to support their point of view. But at other times, people are not aware of the degree to which their deeply held biases influence their interpretation of the scientific data. The human brain, after all, is programmed to filter out information inconsistent with its basic worldview.

I suspect that legalized abortion probably does reduce crime. But even if I accept that truth, it does not necessarily make me an advocate for abortion. There are lots of actions that might reduce crime – locking up anyone who looks remotely suspicious, reinstating the Code of Hammurabi or Old Testament law, sticking surveillance cameras on every square inch of public property, sterilizing people who cannot support children – which most of would oppose on legal or ethical grounds. There is more to life, after all, than reducing crime.

But it is dangerous to reject scientific conclusions simply because you do not like them. On so many issues – creation/evolution, global warming, fiscal policy, etc. – people’s opinions on scientific questions have little to do with science. And people who base their beliefs on what they want to be true are living in a fantasy world, and if they persist in this tendency, they will over time lose the capacity to learn. They might also find themselves pissed off by people like those Freakonomics guys, who have the annoying habit of going where the data leads them.