Does School Work? (Or is it a Flawed Concept?)

Check out my new book

I recently published a book called "Accessible American History." It developed from my eleven years of experience teaching community college American History, and home schooling parents might find it particularly useful. The link below will take you to a hub that provides more details, including links to where it can be purchased.

A Song About a Job "Well done" by a School

Does School Work?

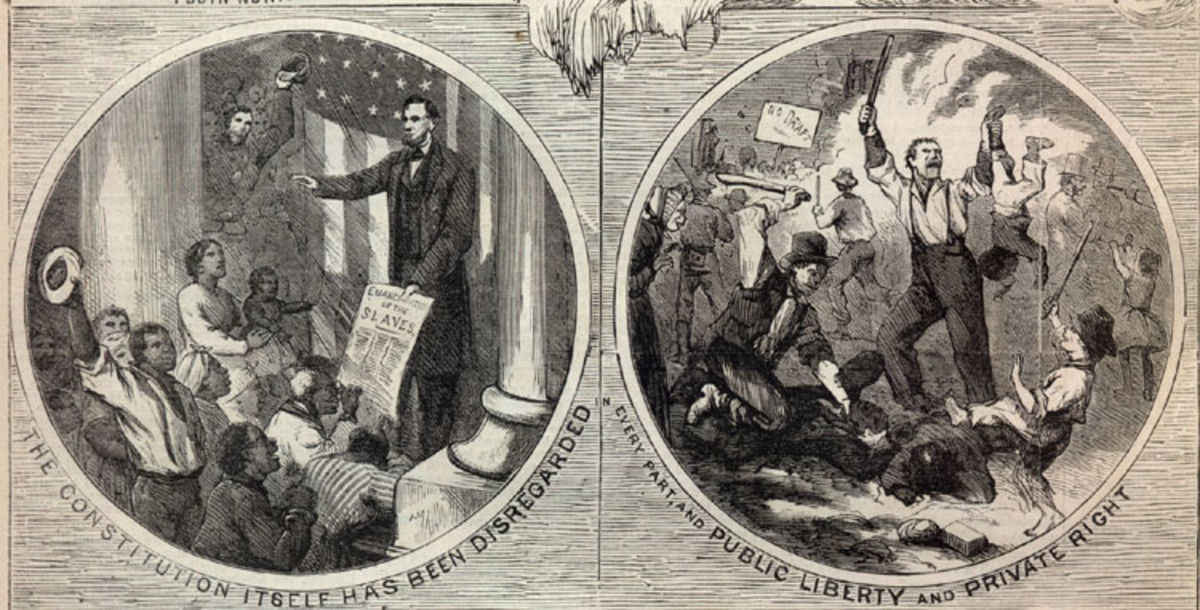

To modern Americans, going to school is both an inevitable and perfectly natural stage in the human experience. It’s as natural for a child as learning to walk, becoming potty trained, or discovering the joys of sugary food. As a history teacher, however, I am well aware of the fact that school as we define it is a modern human invention. Schools in some form or another have been around for thousands of years, but the overwhelming majority of people in both civilized and non-civilized societies did not attend them. And yet, somehow, people learned what that they needed to know.

I cannot deny that schools perform some very important functions. For one thing, public schools are excellent babysitting institutions. This is an essential function when parents are required to leave home to go to work. Schools also socialize our kids, teaching them basic rules for how people in our culture are supposed to interact with others. I always laugh (inside) when people complain that schools no longer teach values. (What they are often complaining about is the lack of religion in schools.) Teaching has always been about teaching values: don’t cheat, don’t hit your neighbor, obey authority figures, perform tasks on a schedule, etc. It also prepares kids for functioning in the world of work, a world in which their day-to-day reality will require them to obey authority figures, live by the clock, and focus for many hours on tasks that are not necessarily fun. Finally, schools also, unfortunately, play the role of ranking people in society. Through the process of handing out grades and issuing standardized tests, schools separate people into academic categories. These categories may be officially defined by terms such as advanced, intermediate, and remedial, but what is essentially happening is a subdivision between the academic “winners” and “losers.” Students are then prepared for the competitive world they will face as adults, and society gets to pick out the individuals who will most successfully fill the high skill level, high status occupations.

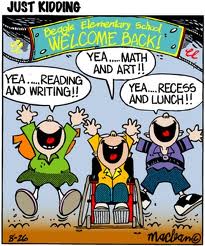

Almost everyone would agree that the tasks mentioned in the preceding paragraph are important functions of schools. If you ask people why we have schools, however, their first answer will most likely have something to do with academic learning, not socialization: reading, math, writing, and, sometimes, even science and history. (Sorry, I mean “social studies.”) And since most Americans went through some type of school system, we assume that schools are the natural place for kids to absorb all of this information. Having taught for many years, I have concluded that schools as academic institutions have some fundamental flaws. Now some might wonder, of course, why a person with this point of view would be working as a teacher. Am I just another frustrated educator looking for excuses? Others, however, might be dumbfounded by my point of view. After all, where else but in a school could a person learn the essentials?

In order to avoid the jaded educator label, I better support my argument that the American concept of school is fundamentally flawed. To make my case, I will start by going back in time to societies in which few or sometimes none of the people went to school. Schools were rare or non-existent, but few would doubt that education took place. But how did people learn? The answer, of course, is pretty simple: people learned things on a one-on-one basis. If you lived in a hunting and gathering society, you would learn basic survival skills from the elder members of the clan. If your parents were farmers, you would learn agricultural skills from your parents. People who went into manufacturing trained for several years as a journeyman and apprentice under a master craftsman. A person pursuing a more “academic” career field would often work under a private tutor.

This one-on-one system of learning had several advantages. First, students were able to learn things at their own pace and receive instruction specifically designed to meet their particular needs and match their learning style. Second, people typically learned skills by doing things, not by having a person or book impart information to them. Finally, a student often received the undivided attention of the instructor. School as it is traditionally defined, of course, cannot replicate this experience. Students are expected to move at a pace dictated by the teacher or by some standardized guideline defining the proper so-called “grade level.” They often sit passively while the teacher instructs them and are forced to work with a teacher who is unable to focus on any individual for a significant length of time.

When I look back at the many education courses I have taken and seminars I have attended over the years, I recognize how well aware many educators are of the inherent weaknesses of schools. They talk about the importance of individualized instruction, of active learning techniques, and of small class sizes. While I applaud these efforts, I am also struck by a simple fact: these “modern” teaching techniques and reform efforts are simply trying to recreate the educational experiences of people who lived in the days before schools were common. And since schools can never fully replicate these experiences, why do we continue to use the modern school model?

Some people have decided to move away from the school model. Millions of Americans have chosen to home school their kids, and from talking to people I know who have made this choice, home schooling has taken on the qualities of a political movement. My wife and I have come close to taking the plunge, but for the moment, we are sticking with the school model. And though I hate to admit it, my reasons for keeping the kids in traditional schools have little to do with education. I continue to have this nagging sense that school is important for the development of my kids’ social skills. There is also the more selfish desire to have a little more time to myself than would be possible with home schooling. Under the right circumstances, however, I think that the home school model is more effective academically than traditional schools.

For many Americans, however, the circumstances are not right for home schooling. Many parents, of course, cannot devote the necessary time because they are working full-time. Other parents do not have a sufficient academic background. In the past, when parents primarily educated their kids, all that was required was a basic knowledge of the skills necessary for their child to perform their future occupation (which was often the same as the parents’ job). But given the explosion of information that has taken place over the past 125 years, along with the huge increase in the number of potential occupations, it is almost impossible to have even a basic knowledge of the many specialized fields that we assume are a part of a well-rounded education. Many kids, of course, have parents who lack the necessary English speaking skills. Some kids have no parents in their lives at all.

Schools, then, are the only practical option for many of the kids in our society. So if we are stuck with schools, then people like me should stop complaining about their weaknesses and make the most of the situation. It is no secret what needs to be done. Nearly everyone agrees that it is a good idea to give students more freedom to move at their own pace, incorporate active learning strategies, use portfolios to provide more comprehensive assessments, and utilize a variety of teaching strategies to appeal to different learning styles.

The basic problem is that it is very difficult to incorporate these strategies in a classroom with between 30-40 (and sometimes 50) students in it. It is difficult to assign portfolios and various projects because there will be so many things to grade. Coming up with assignments that are adapted to individual student needs becomes increasingly difficult as the class size grows. Creative, cooperative learning exercises can easily turn into mass chaos in a classroom with lots of students. I know from past experience as a junior high and high school teacher that I was often scared to experiment with more interactive teaching activities because of classroom management concerns. Anyone who has ever worked with children, or even young adults, knows that classroom management often becomes a bigger concern in lesson planning than academic effectiveness. At the college level, some of these problems become even more daunting. My classes generally range from 45 to 140 students. How can a college professor individualize instruction in classes of this size? How elaborate can student projects be when the teacher wants to have some semblance of a life beyond grading papers? It is no wonder that we college teachers so often gravitate toward traditional education techniques and give out multiple-choice tests.

The answer, then, seems simple: keep class sizes low. This is why there has been a big push, particularly for students in the early grades, to cap class sizes at twenty students. So why not do this at all grade levels? The answer is once again simple: money. It costs far less to pay one teacher to teach 40 students than two teachers to teach 20. And since most American students attend public schools, the money issue is essentially a political issue.

Explanations for why schools cannot provide enough money to maintain small classes vary depending on one’s political ideology. Many democrats would argue that schools are not funded enough. They might also throw in some of the stereotypical “bleeding heart” liberal statements about our society not valuing children enough because we apparently have other priorities. A conservative republican, on the other hand, would argue that the “lack” of money is more an issue of mismanagement. This is a part of their general argument that the government as a general rule spends money foolishly and inefficiently. Why should they spend money wisely in an attempt to provide a quality service if they are going to be paid through tax dollars no matter what? This is why conservatives often support school voucher programs that will give individual citizens money to spend on the school of their choice. If schools are forced to compete, they will provide a better service.

I am tempted at this point to pour myself into research to find out how well schools are actually funded or to evaluate the success of current school voucher programs. I know, however, the extent to which statistics can be manipulated to make a certain argument. I also know that I will probably end up in the same place where I generally fall: somewhere in the middle. Like democrats, I do not think that education in our society is as high of a priority as it should be. However, I also sympathize with the frustration republicans feel toward American public education. Too much money often goes into administration rather than education, and both teachers and schools are not held accountable enough for their poor performance.

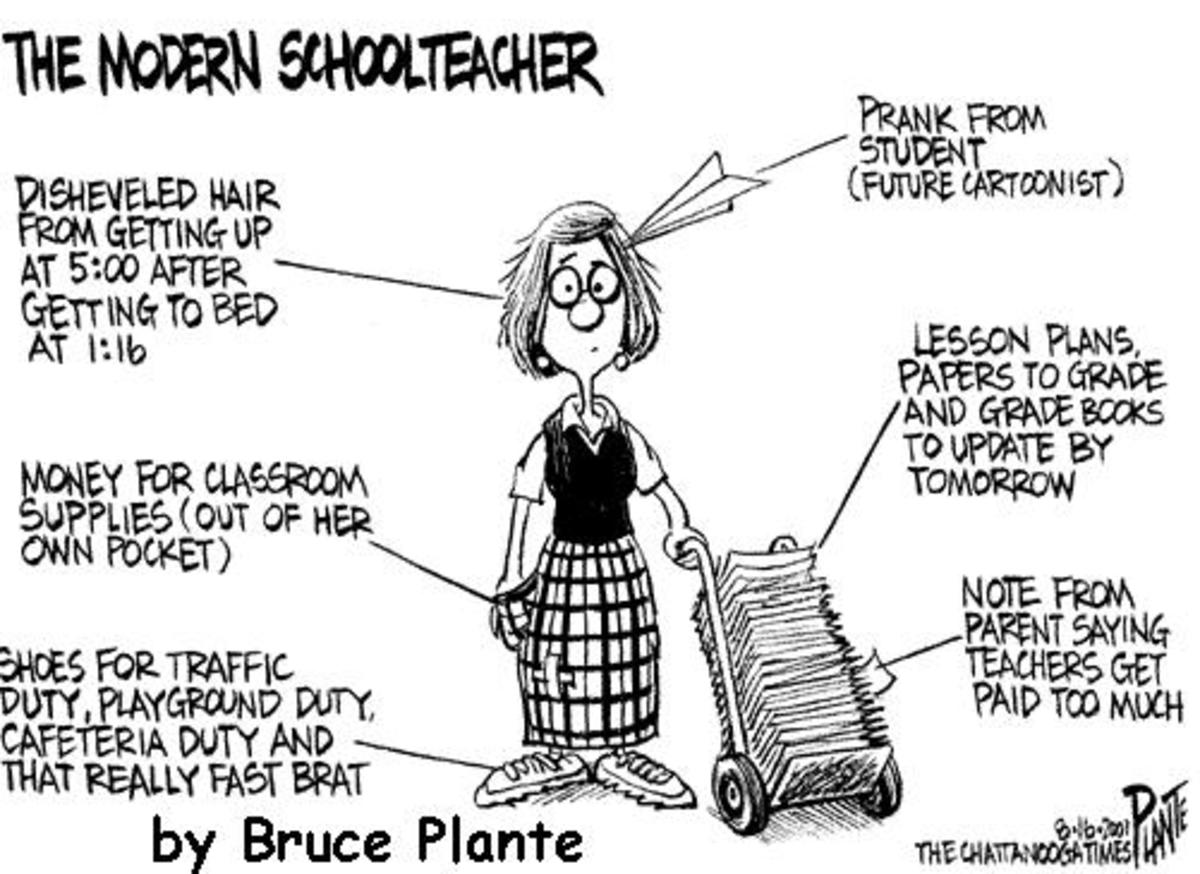

Too often, however, the wrath of the general public is directed toward teachers. In some cases, this may be deserved. But before people start yelling and screaming about teachers, they need to look at the setting in which a teacher is expected to operate. What is remarkable is that there are so many teachers out there who are often able to be effective in a classroom where they are almost set up to fail. Of course, there are many others who are unable to find this level of success. A large number of teachers end up leaving the profession after a very short time. Others start with high hopes and eventually get burned out, but they stay on the job, learning to lower the expectations that they have of their students and themselves.

This may sound overly optimistic, but I tend to think that most of the people who go into teaching genuinely want to do something positive in their student’s lives. Not all of them are extremely talented, and some would probably be better suited for something else. But these teachers of average talent whose heart is in the right place would generally be successful if provided with the proper resources and classroom environment. Teaching in a school setting is a challenge under the best circumstances. It is almost impossible in some of the situations that our society throws teachers into. I don’t know if this is the fault of politicians, school administrators, or the general public. When a teacher is standing in front of a big group of students, it doesn’t really matter. I would love to see some of our society’s teacher bashers stand up there and try to do better.

![Flowers Are Red [Clean]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51W6QMMkUzL._SL160_.jpg)